The pig transport ship departed from Portland. The ship's name was the Owen. It set sail on August 31, 1949. However, two days later, it encountered a violent storm, blowing away the pigpens on the deck and sending white pigs flying into the air. The ship returned to port, restocked the pigs, rebuilt the pigpens, and set sail again on September 4. The voyage was no easy one, as it encountered storms and mines on the way. Thus, it arrived at its destination, White Beach in Okinawa, on September 27, much later than planned.

But why were the pigs sent across the sea to Okinawa?

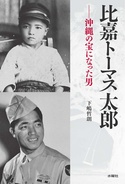

I pursued this mystery and a certain person emerged. That man was Thomas Taro Higa. He was a second generation Hawaiian of Okinawan descent. He was the mastermind behind "The Crossing of the Pigs." Who was he?

* * * * *

Taro was seriously injured twice during the fierce battle of San Remo, Italy, where over 40% of Japanese soldiers were killed or wounded, and was escorted to a hospital in his home country. Then, JACL president Saburo Kido came to visit him and asked him, "I would like you to tell the Japanese in the internment camp about your experiences on the battlefield - the 'facts'."

At that time, rumors were flying around that "Japanese soldiers were just shields for the white soldiers. Japanese soldiers would charge first, then black soldiers, and finally white soldiers." Taro says.

"Facts: There are no races on the battlefield because bombs are fair. These are facts."

Taro sneaked out of the hospital where he was recuperating and gave a lecture tour of 10 Japanese internment camps, 23 Japanese segregation centers, and Japanese towns scattered across 40 inland states to convey the "truth" of the battlefield. The tour covered a total of 37,000 kilometers, almost one lap around the globe. The 45-day schedule was four times longer, totaling 180 days. And he was still wounded. Moreover, it was a poor trip, almost entirely at his own expense, on the low salary of a private first class.

The final lecture location was the Manzanar internment camp in California. There Taro had a fateful encounter with Reverend Herbert Nicholson. The pastor had been evangelizing in Japan for 30 years, but returned to Japan when war broke out between the United States and Japan.

There is something else we should know here. In each of the internment camps, there was a pastor who was pro-Japanese (not pro-national). These men and women had lived in Japan for many years, and they saw through the seemingly ambiguous Japanese character (for better or worse), and loved it. The noble spirit of these pastors, who transcended national and racial boundaries, worked in the internment camps to provide physical and mental relief to the Japanese who were being unjustly interned.

He was the person in charge of Pastor Nicholson's Heifer Project, "Donating 200 milk goats to Japanese children." The day was October 10, 1944, the day before the U.S. military air raid on Naha City, Okinawa Prefecture. Taro, who knew the tragic reality of the people who suffered the devastation of war during the Italian War, and the "facts" of war, said:

"Mr. Nicholson, the place that needs help now is Okinawa."

The pastor reluctantly changed his destination to Okinawa, and after seeing the tragedy of the people there, he said, "I want you to forgive us Americans."

"I thought the message of the goat was more important than the goat itself."

Taro says, "The United States of America is a profound country with fair-minded people."

The pastor became affectionately known as "Goat Uncle" to Japanese children whose hunger was saved by goat's milk, and this story even featured in textbooks.

Taro had a unique idea for this project. It was about pigs crossing the sea, which, from Okinawa's point of view, looked like "pigs came from the sea!"

Okinawa is a country with a pig culture. The US military is about to land on Okinawa, and a ground war is imminent. Taro had a premonition that a repeat of the massacres of the Italian front would be inevitable.

Taro had a great talent for reading the future and was a man of action who would act immediately. This can be seen from the fact that he was sent to Okinawa when he was three years old, and left for Osaka to earn a living when he was only nine years old. On the day he left Okinawa, Taro made a vow in front of his former teacher, wrapped in the cool shade of the large banyan tree at his alma mater.

"I want to become a person who is of benefit to the world and to people, just like this big banyan tree."

Taro never broke his vows or betrayed himself throughout his life. Most people reach a turning point in their lives where they wonder, "Is this really the way my life is?" But it's normal to just carry on as is. That's why Taro's life, in which he never betrayed his 9-year-old self, and in which he lived "for the sake of the world and for the sake of others," not for himself, is extraordinary.

Taro returned to Hawaii and immediately launched the Okinawa Relief Movement. To see the actual situation, he volunteered to serve in the Okinawa Ground War. Perhaps because he was a wounded soldier close to being discharged, Taro Higa served as a soldier without a unit. After inspecting various areas of Okinawa where fierce fighting was taking place, he sent the following telegram to the Okinawa Relief Movement in Hawaii.

"Not a single pig in the pigpen." This was the first report from the inspection.

This report put the Okinawa relief movement in Hawaii into full swing, and in a short space of time they raised a lot of money to buy pigs. With this money they bought 550 pigs in Portland, because they couldn't get enough of them in Hawaii.

The breakdown was 500 sows and 50 breeding boars. This figure was based on a veterinarian's calculation of the reproductive rate. According to that, just four years later, the number had increased to over 2 million! According to statistics, the highest number of pigs in Okinawa before the war was 100,000, which was reduced to 2,000 during the war. It sounds like a dream, but... it was a dream. The veterinarian forgot to include an important coefficient in the calculation. They were starving, and they ate the breeding pigs. Nevertheless, four years later, the number had reached a record high of 140,000.

By the way, Okinawa originally had black pigs. The 550 pigs that were donated were white pigs. With this, Okinawa has completely changed to white pigs. The impact of this change is clearly expressed in a letter of thanks from an Okinawan.

"The pigs that you have sent as a sympathy gift from Hawaii are pure white, just like in America. It is the first time I have seen such beautiful pigs. Everything in Hawaii is beautiful and different."

The Okinawa relief movement expanded into many areas, including clothing, medical care, and education, and then spread to Hawaii, the entire United States, Central and South America, and the world. In Hawaii, "1,350 boxes big enough for a person to lie down comfortably were loaded onto the trucks, which departed one after the other for the port where the ships to transport them to Okinawa were waiting. When the last truck departed, people shook hands in joy. It was a great emotion." (Notes from a participant in the movement).

The campaign was a great success, providing funds for the reconstruction of war-torn Okinawa. However, we must not forget that behind the scenes, there were pastors: Dr. Gilbert Bowles in Hawaii, Reverend Hiler on the American mainland, and Sweetsland of the American Red Cross.

* * * * *

In 1946, in the midst of the Okinawa relief movement, Saburo Kido of the JACL visited Taro again and said, "The Japanese who were released from the internment camps were homeless, and there was a tremendous amount of Jap hatred." He began by saying, "We have launched a nationwide 'Citizens Association Committee Against Discrimination' to demand the right to naturalize Japanese people (revision of immigration laws), and an apology and compensation for the forced evictions." However, "We are facing the state. (Japanese people) are afraid of future problems, and the movement is extremely difficult. Our only hope is Hawaii, where there is a large Japanese population. Please become the pillar of the movement in Hawaii."

Taro accepted the job. He put all his effort into it. And he did it for seven years. "I didn't do it because I was financially well off," he said. In fact, the house was on the verge of being auctioned. Still, he didn't betray the promise he made to his nine-year-old self.

Taro began the Okinawa relief movement at age 29, which lasted for seven years and was resolved in 1952 with seven family members. The former movement, "Immigration Law Reform" and "Apology and Compensation for Forced Eviction" passed the U.S. Congress on June 27 of the same year. Donations raised nationwide totaled $643,140, of which $88,196 was raised in Hawaii by Taro. More than 40,000 signatures were collected. However, this was only the first step. The revised immigration law set a quota of 98% for European immigrants, with only 185 Japanese. It took another five years to revise the law, and the resolution was reached in 1965. Today, more than 1.5 million Japanese are active in the U.S. as a matter of course, but we must know and never forget that this is the benefit of Taro, the JACL and others who continued their movement for more than 20 years without making a single yen from it.

Taro's final work, having lived this way, was a self-financed documentary film about the history of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, "Living in Hawaii." As I've run out of space, I'll have to wait for another opportunity to tell you about it.

Finally, Taro's family of seven was generous and warm, despite their difficult lifestyle. E, the youngest daughter, cheerfully says:

"We were poor! For dessert after dinner, seven of us shared one apple."

The bright, poor life naturally fostered a "spirit of sharing" in the children. In Japan, there is a beautiful phrase, "Kimori Ringo." The last apple is left as an offering to the God of Nature. The Higa family had a single apple at the top of the apple tree, shining like a bright red apple offered to the God of Nature.

* * * * *

Nowadays, it is difficult to get the chance to hear from second-generation Japanese-Americans. However, we must not forget that not only Japanese-Americans today, but also Japanese people today, have benefited from them.

With this in mind, I published a biography of second-generation Japanese, Higa Thomas Taro, titled "Higa Thomas Taro - The Man Who Became Okinawa's Treasure" (Suiyosha) in June of this year. However, the first language of Japanese-Americans is English. I am looking for someone in the United States to help me publish the English version.

© 2024 Tetsuro Shimojima