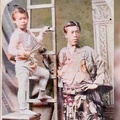

It is a privilege to be able to write about my family’s ancestral Japanese roots, especially given the significance of Sakuragawa Rikinosuke, who is recorded as the first Japanese to settle in Australia. Technically, this pioneer was my great-great-grandfather, but the bloodline actually begins with his son, Ewar Dicinoski (Togawa Iwakichi), who was seven when they arrived in Australia in 1873.

We are still unsure whether Ewar was Sakuragawa’s biological or adopted son, or his protégé. Nevertheless, they were ‘father and son.’ Sakuragawa also brought his 10-year-old daughter, Makichi Sakuragawa Ume, but she returned to Japan in 1875. Sakuragawa Rikinosuke is reported to have been born in Edo (former name for Tokyo) in 1848, and Togawa Iwakichi as born in Edo in December 1865.

Japan had barely begun to engage the West under the Meiji Restoration, following the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate that ruled during the Edo Period. At this time, there was a policy known as sakoku, which controlled international travel and trade by Japanese. However, this was repealed in 1866, and passports were issued for purposes of study and trade. Interestingly, under a loophole in Japan’s strict rules on the issuing of passports, foreign entrepreneurs were able to endorse and support passport applications for numerous Japanese acrobats to travel and perform abroad.

Research shows passports were issued by Yokohama prefectural authorities on 7 October 1872 to Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Togawa Iwakichi. The next day, 8 October 1872, they departed Yokohama on aboard P & O’s Avoca (headed for London via Kolkata, formerly Calcutta, India), and appear to have been in the employment of French entrepreneur C. Pasquale.

Subsequently, they departed Calcutta under the employment of Thomas King, and arrived in Sydney aboard the R.M.S. Baroda on 29 July 1873. They were part of a group of 13 Japanese performers, and were accompanied by King. Actually, the R.M.S. Baroda manifest for that day lists ‘Mr and Mrs King with 18 Siamese troupe.’

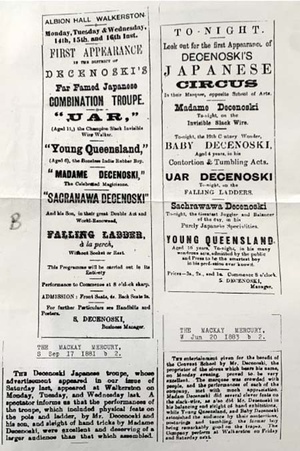

After performing across Australia and New Zealand, Sakuragawa married Jane Kerr in 1876 in Fitzroy, Melbourne, one of few Japanese immigrants to marry an Australian. For the next few years, Sakuragawa raised a family and continued to work as a circus performer and travelled around Australia from town to town.

In 1882, he decided to settle and take up farming in Herberton, Queensland, and applied to be naturalised in order to secure a homestead on Crown land—this marked his entry into the history books as the first Japanese settler in Australia. The farming venture did not work out, so Sakuragawa went back to being an acrobat. Unfortunately, he died in June 1884 from tuberculosis and was buried at Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney.

Upon arriving in Australia, the name Rikinosuke was phonetically recorded as ‘Decenoski,’ which became the name used thereafter by Sakuragawa until his death. In fact, he was recorded as using ‘Sacarnawa Decenoski’ for most circus performances, and he also adopted ‘Reginald’ as an English first name.

His son, Ewar, also used ‘Decenoski,’ but after Sakuragawa’s death, changed this to ‘Dicinoski,’ which was recorded officially upon his marriage on 20 February 1892, at the age of 26. Ewar married Susan Bowtell, who was 16 years old in Warracknabeal, and they went on to have 11 children, though sadly, two died quite young. One of them, Ewar junior, was my grandfather, who was affectionately known as ‘Hughie’ (another variation of Ewar, whose origins lie in ‘Iwakichi’).

Having joined numerous circus troupes, including Ashton and St Leon, Ewar senior eventually established the ‘Dicinoski Troupe’ in 1900, which consisted of his growing family. They travelled to all states of Australia. The unique surname ‘Dicinoski’—only found in this bloodline from Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Togawa Iwakichi—remains to this day, and was my mother's maiden name.

For many reasons, the Japanese lineage has been a curious question in recent years in my family. It was once investigated by one of my aunties, but in a non-globalised and non-digital world. Things seemed to come to a halt also with the untimely passing of a key Australian National University researcher, Dr. David Sissons, who was a skilled proponent of knowledge about the Japan–Australia relationship, and was fascinated with our family connections as they related to the commencement of culturally significant bilateral relations. Most of the records that I have are testimony to the excellent research efforts made by David Sissons.

I would like to say that interest in our Japanese lineage has always been strong in our family, but this is not the case. In fact, I do not recall this ever being a topic of conversation while I was growing up and well into my young adult life.

The truth is, my mother and her sisters were quite proud to be from northern Queensland (Delulu, Mount Morgan, Rockhampton) and to be ‘simple country’ people, and they did not speak of their Japanese origins, for they were simply not aware of them.

My grandfather, Ewar ‘Hughie’ Dicinoski, after being raised as a circus performer with the Dicinoski Troupe to about age 20, worked as a stockman, jockey, and horse breaker for most of his adult life.

I wondered if at some point, there was a conscious or unconscious decision, or perhaps just a natural transition, to overlook or suppress our ancestral Japanese roots, and I felt compelled to question my mother about it. She responded that they never asked about their father or mother’s family history, as it ‘was just not done; it was a different age back then. You certainly did not ask such questions of your parents.’

I asked if they, or others in the community, were ever curious about their father’s obvious Asian appearance, as he was half Japanese, but none were. I queried, ‘why did they think their father had never told them about the family’s Japanese history’? And they gave the same response. ‘It was just not done.’

In fact, according to my mother, the first that any family member knew of our Japanese ancestry was when one of their uncles Reginald—Ewar and Susan’s first child—was contacted in the 1970s in relation to official records.

For me, this is astounding, and somewhat saddening at the same time. And I lament the loss of historical family information that could have been passed on and shared. The key to the family’s lack of knowledge about ancestral Japanese roots lay with Ewar Dicinoski.

Noting the realities of historical events and the White Australia policy, I wondered if the ‘Japanese-ness’ was suppressed intentionally by great-grandfather Ewar Dicinoski, so that he and his large family could simply be ‘Australians.’ My mother believes this could be a distinct possibility, but common sense provides another explanation.

Ewar was only seven years old when he arrived in Australia, so he essentially grew up in Australia like any other Australian child. Linguistically, he could have been bilingual if he had maintained his Japanese language, but this seems not to be the case.

His relationship with his adopted father, Sakuragawa Rikinosuke, remains a mystery. For all intents and purposes, Ewar was a country person with a country accent, but looked Asian. However, my research revealed that a time came when Ewar faced his Japanese heritage and felt the need to take action.

All photos courtesy of Dawson Family archives unless otherwise stated. This includes historical photographs donated to the family by the late D. C. S. Sissons.

*This article was originally published in the Nikkei Australia website on August 29, 2020.

© 2020 Steve Dawson