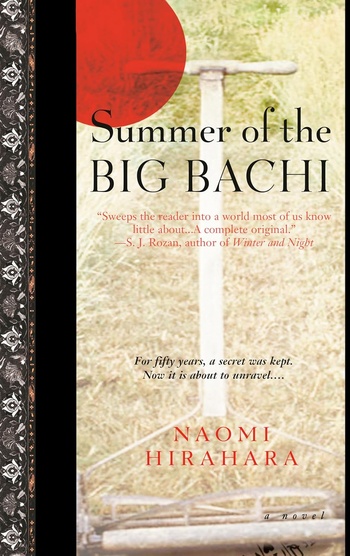

2024 marks the twentieth anniversary of Naomi Hirahara’s novel, Summer of the Big Bachi. This kickstarter to the Mas Arai mystery novel series pays homage to Hirahara’s late father, who was a gardener—the main character, Mas, is a gardener as well. Through careful integration of personal experience, fiction, Japanese history, and the multicultural scenery of Los Angeles, Hirahara crafted a book that has impacted both her life and the lives of others over the past 20 years.

Reflecting on the reach her novel and the main character had on others, Hirahara states: “Mas, he resonated with certain people. He resonated with Japanese Americans who had a gardener in their family. He resonated with people in that area, with Angelinos.” Her novel managed to tell a story that aligned with the experiences of many others, making it that much more meaningful.

In a discussion on how Summer of the Big Bachi’s mystery genre format impacted the audience, Hirahara mentions: “It’s not like a history book. People may come to my work thinking… ‘I want to solve the mystery.’ And then while they’re doing that, it just so happens they’re exposed to these communities’ struggles and political victories as well.” She describes how this format has allowed people unfamiliar with Japanese history to digest it more easily.

Hirahara also touches on how the mystery genre allowed her to break Japanese “model minority” stereotypes and focus more on the humanity of the community: “We make mistakes. We’re emotional. We are not stoic. People have done bad things, and some people have been arrested. And I think that’s why I like the genre because it’s built in.” Hirahara adds, “I think that especially the Nisei felt like they had to present themselves in a certain way or else they would end up in a place like the incarceration camps.”

When asked to reflect on where the inspiration for Summer of the Big Bachi comes from, Hirahara draws on two aspects: her personal experience and her family. Regarding the incorporation of Japanese American history, she says:

“Being a journalist and working at a community newspaper was really eye-opening for me. My years at the Rafu Shimpo, during the redress and reparations movement… I think that really informed me and opened my eyes. Even though Japanese Americans may not have that personal direct connection to World War II incarceration, the fact remains that if we were alive during that time, we would be among those rounded up and labeled as aliens.”

Hirahara additionally notes that her parents were both “Hibakusha” (referring to survivors of the WWII atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki), which is reflected in her novel’s integration of Hiroshima’s bombing. She also considered how she could include and honor her father’s experience working as a gardener: “I think in my own way, [I thought:] how can I stand up for my dad or people like him? And it wasn’t like this character was going to be a superhero. He was going to represent the type of person [my dad] was.”

Looking back on the writing process of Summer of the Big Bachi, Hirahara says, “Well, it was an ambitious book… I was in my twenties when I first started it; I was attempting to write about a person much older than me and male.” She describes how unusual it was at the time: “That wasn’t the trend, especially in Asian American literature. It was more like a female writing about a young female dealing with her generational issues—her parents or grandparents.”

She also shares how she went through numerous rewrites and revisions: “Initially I wrote it from two points of view—not only Mas but also a young doctor from Hiroshima. In a nine-month writing fellowship, my writing mentor there said Mas is a much more memorable and dynamic character than the doctor, so I had to do major surgery… to write it from just Mas’s point of view.”

Despite her past challenges, she happily shares how fulfilling the process was too. “Publishing is very tough,” she says, “[but] I was able to close out the series in a way that I was really happy with. I feel very much at peace with how Mas progressed in these books.” Hirahara continues, “He’s a fictional character, but it’s really lovely to hear that especially non-Japanese readers relate to him. They’re rooting for him; some of them are in love with him. That makes me really happy, and I’m so relieved.”

Hirahara describes how writing has impacted her life and opens up about feeling fortunate to still be able to think creatively at this stage of her life. She describes her brain as her “playground” and says, “I think being in that place is such a joy. Even if it’s dealing with horrific things or dead bodies, it’s still so nice to be able to open that door to that imaginary world and kind of walk through it.”

She speaks with earnest passion regarding her writing. Even when posed with a question about how Summer of the Big Bachi has changed her life, she responds: “Kind of completely. I think it’s really wonderful. I feel very fortunate to have spent the past two decades writing fiction.”

Ultimately, Summer of the Big Bachi has created space for all kinds of people—Japanese Americans, the Los Angeles community, and even those who haven’t had a previous connection to the story’s setting, culture, or history. In a short anecdote, Hirahara recalls how one reader told her he showed Summer of the Big Bachi to his Japanese gardener, and discovered through conversation that he was also an atomic bomb survivor. After relaying that story, Hirahara mentioned she was happiest when she found out that “the book can open up conversations between people.”

For the future—and for all readers who continue to read her book—she says: “I hope that notions of who is American are challenged… there’s so much diaspora in people’s lives, and sometimes we get locked in. I hope readers expand their worldview and embrace people.”

© 2024 Lauren Rise Masuda