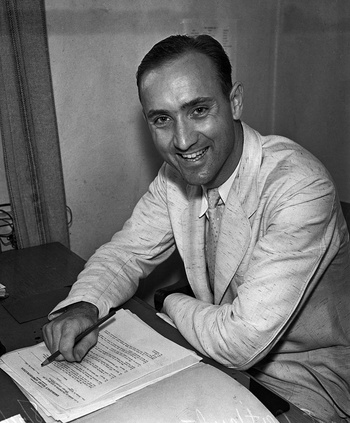

As part of my ongoing study of the ways in which Congress shaped the lives of Japanese Americans in the World War II period, I have recently come across the career of George E. Outland. Recently, during a trip to the California State Library in Sacramento, I came across Outland’s personal papers. I knew that Outland was a member of the California congressional delegation during the war, but what surprised me was Outland’s ranging interests in the treatment of Japanese Americans during his brief but important career in the House of Representatives.

I believe Outland’s political career offers a fascinating case study of how moderate members of Congress addressed the anti-Japanese movement. While some, like Alfred Elliott, openly called for the deportation of Japanese Americans, Outland neither condoned nor openly condemned such remarks, underscoring both acts of courage on Outland’s part along with times where he compromised his ideals.

George Elmer Outland was born in Santa Paula, California on October 8, 1906. From a young age, Outland began exploring a career helping the marginalized. In 1924, when Outland was in high school, former Democratic presidential candidate and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan gave a speech at his school. Outland was asked to introduce him.

Extremely nervous, Outland described being “scared to death” by the speech. Bryan himself approached Outland afterwards and asked if he was nervous. When he replied yes, Bryan told him, “That's a good sign. Always be nervous. If you don't, your speech is going to fall flat. I try to work myself up to be nervous before I speak.”

The moment inspired a young Outland—touched that someone of such political importance wanted to speak to him—to pursue a career in politics. After high school, Outland attended Whittier College, where he earned a bachelor’s in sociology. He then got a master’s in history and government at Harvard, then pursued a career in social work during the Great Depression.

He worked for five years as a case worker in Boston, them moved to Los Angeles. There Outland found a job as director of boys’ welfare for Southern California as a part of the transient bureau of the New Deal agency Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

After a two-year stint in Los Angeles, Outland decided to round out his education by completing a PhD in education at Yale University in 1937. During an interview about his career in later years, he listed his credentials and then jokingly told the interviewer “now you tell me what my specialty is.”

In September 1937, Outland became an instructor of social science at Santa Barbara State College (which later became University of California, Santa Barbara), where he continued to study the conditions facing transient youth in the American Southwest during the Great Depression. Even as he pursued his teaching, Outland continued his social service work with the Santa Barbara County Council of Social Agencies.

After being appointed director of recreation by the County Council, Outland used his position to train students about government work, arranging internships for his pupils with the different agencies. The Santa Barbara News-Press applauded Outland for his resourcefulness and his civic engagement. He also became engaged in local politics.

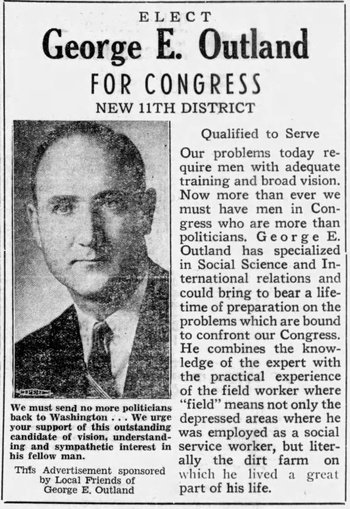

Outland’s engagement with local politics paid off in April 1942, when he received the endorsement of Santa Barbara County Democrats to run for representative of California’s 11th congressional district. Outland was not a natural politician; he was a political scientist who took advantage of conditions to run for Congress.

Running against Oxnard Republican A.J. Dingman, Outland campaigned as a native son of the region who would advocate on behalf of the interests of local businessowners and ranchers. Dingman’s campaign (in an anticipation of Richard Nixon’s successful campaign against New Dealer Jerry Voorhis four years later) attempted to slander Outland as unpatriotic and controlled by communistic labor unions. Outland responded in the press by asserting that Dingman spent so much time trying to wear down his opponent that he forgot to actually propose any policies. In a close race, Outland beat Dingman by 900 votes, representing less than one percentage point.

The story of Outland’s connection with Japanese Americans is even more mysterious than his unusual political career. In March 1928, while Outland was a student at Whittier College, he performed with the school’s Cosmopolitan Male Quartet at the Japanese Southern California Association (JSCA) Vodette.

In February 1940, James Ezaki of the Santa Barbara Chapter of the JACL tapped Outland to give a speech about American Democracy at the group’s annual officer’s dinner. The master of ceremonies was Tom Hirashima, a Nisei JACL officer who remained in contact with Outland. Among his other prewar connections with the Japanese American community included Goro Murata, a Nisei journalist who later worked with the Japan Times, and Yamato Ichihashi, the famed Issei Stanford professor who kept a diary during his incarceration at Tule Lake concentration camp.

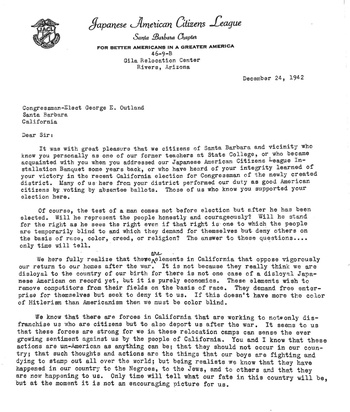

Among Outland’s supporters in the 1942 congressional elections were several Japanese Americans who voted by absentee ballot from the camps. Tom Hirashima, the Santa Barbara JACL officer, wrote a letter to Outland in December 1942 after his victory to congratulate him. Hirashima praised Outland as a marvelous professor, and declared that “many of us here from your district performed our duty as good American citizens by voting by absentee ballot. Those of us who know you supported your election here.”

Hirashima also noted that when Outland was asked whether Japanese Americans should be deported, he had answered in the negative. Hirashima stated that “In so far as we know you are the first California representative who has had the fair-mindedness and courage to answer correctly this important question.”

Outland began his career in Congress in January 1943 at the age of 27. His youth was noted by several members of Congress and the press. Washington Post columnist Drew Pearson shared an anecdote in his column of when Minnesota Representative William Gallagher was lost in the Capitol bathroom. “He boy!” Gallagher yelled to Outland. “How in hell do I get out of here?” Outland kindly showed him the way out, not telling him who he was.

From the beginning, Outland distanced himself from extremist members of the anti-Japanese movement. He voted against the renewal of the Dies Committee, which famously conducted witch hunts against suspected communists and smeared Japanese Americans as disloyal. Outland argued that the Dies Committee was dangerous and un-American for its attacks on civil rights.

In his speech before the House, Outland told his fellow members of Congress that the Dies Committee should be “relegated form the front pages to the obscurity to which it so rightly belongs. Mr. Speaker, a nation at war must have unity. In my opinion, a far greater degree of unity can be achieved if this committee, which is setting one American element against another, which accuses without sufficient evidence, is not given taxpayers’ funds with which to continue.”

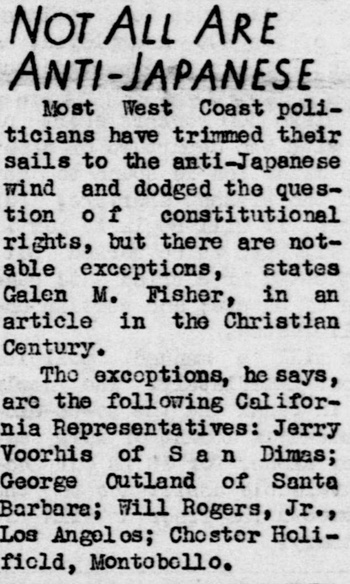

On September 28, 1943, the Gila River camp paper The Gila News-Courier printed a quote from the Christian anti-racist advocate Galen Fisher regarding West Coast politicians. While Fisher nominally described most political leaders as having “trimmed their sails to the anti-Japanese wind and dodged the question of constitutional rights,” he singled out several who had taken principled stands against the anti-Japanese movement. Among them were Jerry Voorhis of San Dimas, Will Rogers, Jr. of Los Angeles, Chester Holifield of Montebello, and George S. Outland of Santa Barbara.

Indeed, as Fisher pointed out, Outland proved to be one of the few moderate voices in Congress among Californians in regard to the WRA’s handling of the camps. Even as members of the state’s delegation such as Representative Alfred Elliott called for the deportation of Japanese Americans, Outland called for more just treatment.

When members of the West Coast delegation called for Myer’s resignation in response to the Tule Lake crisis of November 1943, Outland countered that military control would not change matters. Citing the fact that the Army ran the Santa Anita Assembly Center when a riot unfolded in August 1942, Outland argued that “we are going to have riots no matter who is in charge.” He did, however, join the unanimous petition of the West Coast Congressional delegation calling for the Department of Justice to take control of Tule Lake.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen