Michiko Tanaka was born in the middle of the Pacific War, in April 1943 in the city of Tokyo. During that year, North American naval forces had already taken the offensive by winning the Battle of Midway and managed to expel the Japanese army from the Island of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. From that moment on, the advance of the North American forces would be unstoppable until August 1945 when they entered Tokyo Bay victoriously. The Japanese people, although they were still far from military battles, were the ones who sustained the war with their efforts and sacrifices, and day after day they maintained the enormous military machine of the Japanese Empire that consumed more and more material resources and a growing number. of its population.

In that year of 1943, the Japanese government ordered the transfer of primary schools to rural areas to protect children from possible air attacks. In 1944, Michiko, along with her older sister, Mako, and her mother, Sumiko, who was pregnant, fortunately moved to the mountains of Kyushu, more than a thousand kilometers away from the capital.

In the middle of that year, the US naval forces took the Island of Saipan and in this way the North American aviation, using its gigantic B-29 bombers, had more than 60 Japanese cities within its reach to bomb them openly. In March 1945, the Tanaka house in Tokyo was completely destroyed by the bombers that were already flying in the open sky over Japan due to the inability of the anti-aircraft defenses to reach the height of the B-29s. Traditional bombs and napalm incendiaries left a large part of the capital destroyed and in smoldering ashes, in addition to causing the death of nearly 100,000 people. This bombing prefigured the horror that would be experienced a few months later in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

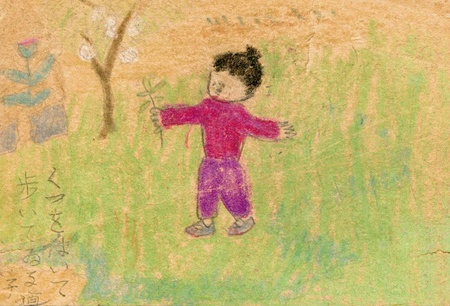

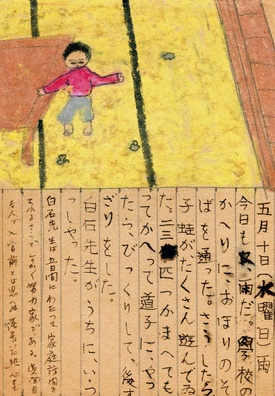

The transfer of the Tanaka family was also due to the fact that Michiko's mother, as I already pointed out, was pregnant. The baby was born in the small town of Fukada, in Kyushu. Sumiko and the three girls found themselves alone as Michiko's father, Toshio, had been transferred to Indonesia to manage a steel plant that the imperial army was building. The family's situation in that small town, although far from the bombs, meant great sacrifices due to the lack of charcoal and even matches that would allow them to cook the scarce and rationed food that each family had. Furthermore, the Japanese government began to organize women and children to take charge of the defense of its territory in the face of the imminent occupation by North American military forces. Thanks to Mako's drawings and diary, as well as his mother's notes, we can reconstruct this stage of their lives.

Michiko's memories do not record those first years of her childhood very clearly; they only began to leave a mark on her memory until shortly after the end of the war. This stage was as painful as the one experienced during the conflict. The population was once again the one who bore the costs of rebuilding the country that was left in ruins. One of the first postwar problems was the repatriation of more than five million people, military and civilians, including Michiko's father, who were in the large areas occupied by Japan, who suddenly had to be fed and given job.

Michiko has those difficult years well etched in her memory. One of his first memories was the long and tiring return trip by train to Tokyo that lasted several days in the summer of 1946. On that trip he remembers how a passenger savored the bunch of grapes he was carrying, consuming one by one as if they were. to last longer. The shortage of food, cooking utensils and other goods, already during the North American occupation, continued for several years to the point that the famine was on the verge of unleashing a great popular revolt. An example that illustrates the terrible situation that was experienced was that rice, the main food of the Japanese people, was not consumed regularly until the following decade.

In Tokyo, Michiko began attending kindergarten at a Buddhist temple. At that time he lived with his paternal grandmother, Oto, who cultivated a small kitchen garden that made it possible to alleviate the family's lack of food. When Michiko began attending primary school, she was able to eat adequately at least once a day due to the school meals program that helped alleviate the malnutrition that children suffered as a result of the war and the destruction of Japan.

Michiko's father was elected in 1946 to the House of Representatives. As a representative of Fukuoka Prefecture, he was assigned a small apartment in Tokyo. The Tanaka family thus had a place to live since many families were forced to live on the streets or in the train or subway tunnels due to the housing shortage that the capital experienced for several years after the war.

The North American occupation of the archipelago ended in 1952, although its army continued to maintain several military bases in Japanese territory. Michiko finished her primary school studies and would immediately enter high school. In those years, he heard the name of Mexico for the first time. Her sister Mako took her to the Great Exhibition of the Arts of Mexico ( Mekishiko dai bijutsu-ten ) at the Tokyo National Museum. The exhibition of pre-Hispanic and popular art and painting of more than 2 thousand objects made a great impression on her and on thousands of people who packed the Museum.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Michiko entered the University of Tokyo, in the Humanities area. When he was already in his first year at the University, in 1962, a call appeared in the press for Japanese students to study in the Soviet Union, at the newly created Russian People's Friendship University, known as Patricio Lumumba.

Michiko was interested in applying for a place at that University, but before making a decision she sought advice from a professor who was a friend of her father, the ethnologist Eiichiro Ishida, who encouraged her to enter and move to the Soviet Union.

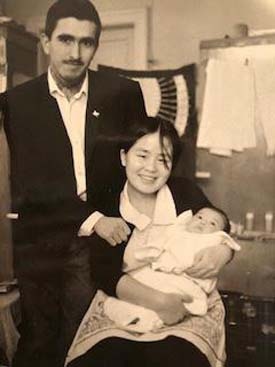

In Moscow, Michiko met several Mexican students who had entered Lumumba. One of them was an economics student, Américo Saldívar, whom she married in 1965 and with whom she would have her first daughter, Emiko, born in Moscow.

At the end of 1967, Michiko graduated with honors in the area of History and together with her husband they had to make a momentous decision: move to Japan or Mexico.

© 2023 Sergio Hernandés Galindo