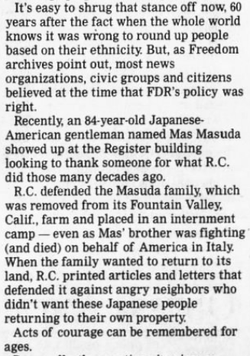

“Acts of courage can be remembered for ages”, wrote columnist Stephen Greenhut fifteen years ago, in November 1992, as he recalled R.C. Hoiles, publisher of the Santa Ana Register (later, Orange County Register and Freedom Communications). Hoiles bought the newspaper in 1935 with a guiding philosophy to “believe in moral principle and have enough courage to express these principles and point out practices and beliefs that violate moral principles.”

Greenhut provided an example of moral courage in his 1992 column by citing a recent visit by an 84-year-old Japanese American gentleman, Mas Masuda. He said Mas “showed up at the Register building looking to thank someone” for what R.C. Hoiles did for the Masuda family and others in the 1940s. The Santa Ana Register was one of the few newspapers to publicly oppose the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, while other publications were stirring the pot of mistrust.

At the time, the Orange County Register staff would not have known they were speaking to a future Congressional Gold Medal honoree, but they knew the significance of the actions taken by R.C. Hoiles and the sacrifice of the Masuda family. Acts of courage seem to come second nature to the Masuda family and Mas Masuda was no exception.

Mas was one of the four Masuda brothers who served in the U.S. military during World War II. He was 24 years old when his family was forcibly removed from California and sent to confinement in Jerome, Arkansas, and later, Gila River, Arizona. On the night of December 7, 1941, the Orange County sheriff came for his father, Gensuke, at their Talbert (Fountain Valley) farm, while his wife, Tamae, and nine children watched.

Long a civic leader in Orange County, Gensuke had been among the Japanese pioneer community—including elders of the Wintersburg Mission—who helped fund a community school in Talbert in 1927. Gensuke and others in the Japanese American community had written a check, and provided equipment and food for children attending grammar school, prompting the teachers to voice their gratitude to the Santa Ana Register.

”It was so sudden,” Mas told Los Angeles Times reporter David Reyes in 1992, of that night on the Orange County farm on December 7, 1941. “They loaded my dad and other parents who were Issei and put them on a bus. We asked where they were taking them, but they didn’t give us any answers.”

After first leaving for Fresno, California, the family was sent to Jerome, Arkansas, and later, to Gila River, Arizona. While waiting to enter the U.S. military, Mas helped support the family by working in camp as a mechanic.

Mas was in the U.S. Military Intelligence Service (MIS), when he learned his brother, Kazuo, had been killed in action in Italy with the “Go For Broke” 442nd. (Read more in the December 10, 2017, post, “Two Decembers: 1934 and 1948.”

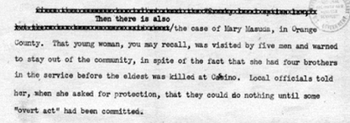

It was while serving in the MIS that Mas learned of his sister, Mary, being threatened verbally and physically as the family began returning to Orange County from the Gila River camp in 1945. The threats by the Native Sons of the Golden West, or what the De Moines Register referred to as “town hoodlums”, prompted a stern response by the War Relocation Authority—and later, by General Joe Stillwell—and made headlines across the country.

The Courier-Journal newspaper of Louisville, Kentucky, was more direct, with a headline “Gang last May menaced sister” on December 9, 1945. The Courier-Journal reported a group of men had “attempted to terrorize” Mary Masuda and that 'the War Relocation Authority listed her case as an 'incident of planned terrorism' against Japanese Americans in California.”

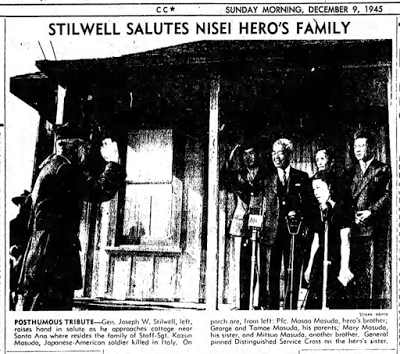

The Distinguished Service Cross is the second highest military award that can be given to a member of the U.S. Army for extreme gallantry and risk of life in actual combat with an armed enemy force. General Stillwell stated during the presentation of the medal that “the Distinguished Service Cross is only a little thing, but in making this presentation, we want to convey to you and your family the deep respect and admiration of every decent American.”

Private First Class Masao Masuda was at the family's Talbert farmhouse, in uniform, as General Stillwell presented posthumously the Distinguished Service Cross for his brother, Kazuo. As has been reported on this blog previously, the future President Ronald Reagan—then an Army captain—was present at the ceremony. Reagan again remembered the Masuda family when signing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, forty years after the funeral services for Kazuo Masuda in the Wintersburg Japanese Church in Wintersburg Village—now Huntington Beach—in 1948.

The legacy of his brother, Kazuo, the family's bravery in the face of threats, and his own service during World War II in the MIS is something Masao Masuda carried for a lifetime as a point of honor. It is a reminder to have courage and stand one's ground for moral principles, the sentiment voiced by the Santa Ana Register's R.C. Hoiles when he defended the Masuda family.

When he returned to Orange County after World War II, Mas wanted to return to farming. Mas gathered his family and constructed a large roadside farm stand that became a popular destination for the best of locally-grown produce. Mas created a good life for his family, while continuing to take a leadership role in community affairs with the Japanese American Citizens League and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Mas got to see his brother, Kazuo, honored as the namesake of Kazuo Masuda Middle School in Fountain Valley and for the Kazuo Masuda Memorial VFW Post 3670. He got to hear President Ronald Reagan speak about his family and their contributions and sacrifice at the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the formal apology and reparation to Japanese Americans.

Mas was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2011, along with an honorary degree from Santa Ana College where he had been enrolled when America entered World War II. He was honored at the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum in January 2017. And, in February 2017, he got to see his brother's uniform and story shared this year on the 75th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Mas saw generations of Masudas take their place in Orange County and passed on his ethics for hard work, along with a love for the sweeter things in life, including his love of sports and fishing. The Santa Ana Register reported his catch of a whopping 33 1/4-pound dolphin fish at the San Diego albacore grounds in September 1976, when he was 59. Mas also passed on his sense of duty in giving back to the community and was a presence at the annual Memorial Day program with Kazuo Masuda Memorial VFW Post 3670 each year, including Memorial Day 2017.

Masao Masuda was as a congregant of the Wintersburg Church—the legacy of the Wintersburg Japanese Mission his family had attended—where his memorial was held on Saturday, December 16, 2017. An Orange County hero.

*This article was originally publish on the Historic Wintersburg blog on December 17, 2017.

© 2017 Mary Urashima