I read on the Discover Nikkei website about a Japanese American granddaughter having to clear out her Nisei grandmother’s house when she passed away. To her shock, she found stacks of plastic tofu containers that grandma “treasured” all her life! I’m sure Canadian Nisei grandparents are the same. However, don’t put the blame on them. It’s the mottainai (being wasteful) spirit.

It probably all started when the first wave of Japanese immigrants came to Canada in the early 1900s, and had to start their lives all over again. The families had very little money to buy luxury items let alone enough food to eat. Parents had to save everything so that they wouldn’t have to use their hard-earned money. Things like sugar and rice were bought. Babies after babies came and it was not unusual for families to have as many as ten children. Scrimp and save was the motto. For Issei families, it was mottainai to throw things away.

Then in 1942 came World War II and the incarceration. Being sent to “internment camps” was for Nikkei families “déjà vu.” Tools and equipment were limited so they had to make do or make their own utensils and tools. Therefore, parents hounded their children about being wasteful. Children with broken hockey sticks would screw or nail the pieces together so they could be used again.

Anything they found, they saved. Carpenters working on a house would bring home bent nails, left-over lumber, and paint. Fathers could repair railings or steps with old nails that were straightened out. Women saved papers, newspapers, strings, paper bags, and cloth rice sacks. Newspapers were useful for insulating the bare walls of the shack and for extra toilet paper. Strings were used to tie vegetables, and paper bags were used to fill up with karinto, homemade candies, cookies, and other snacks. Sisters, Keiko Mayede, Dianne Tasaka, and Sumi Kamachi told me that their father used tin cans by snipping the tin into strips and then twirled them to make it look like icicles. Tin can was also cut into stars and balls. That was the family Christmas tree!

Cloth rice sack was the best money saver. So many things could be created from this valuable material. Once washed and bleached, this cloth could be made into pillow cases and even bed sheets. Do you need underwear? No problem. Rags for the kitchen, sacks to put planer-end firewood, handbags and anything else mothers could think of without having to purchase them.

In the kitchen, one might find glass ketchup bottles with a bit of hot water in to use the last remaining drop. Soap was used right to the bitter end. The last remaining soap was attached to the new soap so as to not waste it. Every bit of food or okazu had to be eaten. Mothers would pick up gohan (kernels of cooked rice) left on the table by their children. Broken or cracked ochawan (rice bowls) made great containers for storing seeds or dried beans.

Issei and Nisei men made bath tubs, wheel-barrows, rakes, and even shovels. Craftsmen could build dressers (tansu), wooden trunks, chairs, and benches. Boys made their own bobsleds, skis, bow and arrows, swords, slingshots, and fishing rods without costing parents any money.

Most mothers had a Singer sewing machine, so most of the children’s clothes were hand-sewn. Moms took old razor blades that were sharp on both ends. These disposable blades were saved by placing layers of tape on one sharp side in order that the other side could be used to cut threads. Another reusable item was old light bulbs, used to darn socks, especially around the heel part. Nisei women were wonderful seamstresses since they all had to learn in school. Many mothers earned extra money by being dress-makers. In Greenwood, there was a sewing class run by Mrs. Tamoto, Mrs. Kurisu, and Mrs. Ooka. On the building that they used, the sign read: Academy of Domestic Arts.

Little boys and girls scoured the town to find empty pop and beer bottles. It was a penny a bottle. They even went to the town dump to find anything useful to be used at home. Toys were made, not bought. Walkie-talkies made from soup cans or toilet paper rolls, Peggi sticks from old broom sticks, katana from pine or spruce for katana-kiri (sword fight), picking berries and wild flowers enabled the children to be resourceful.

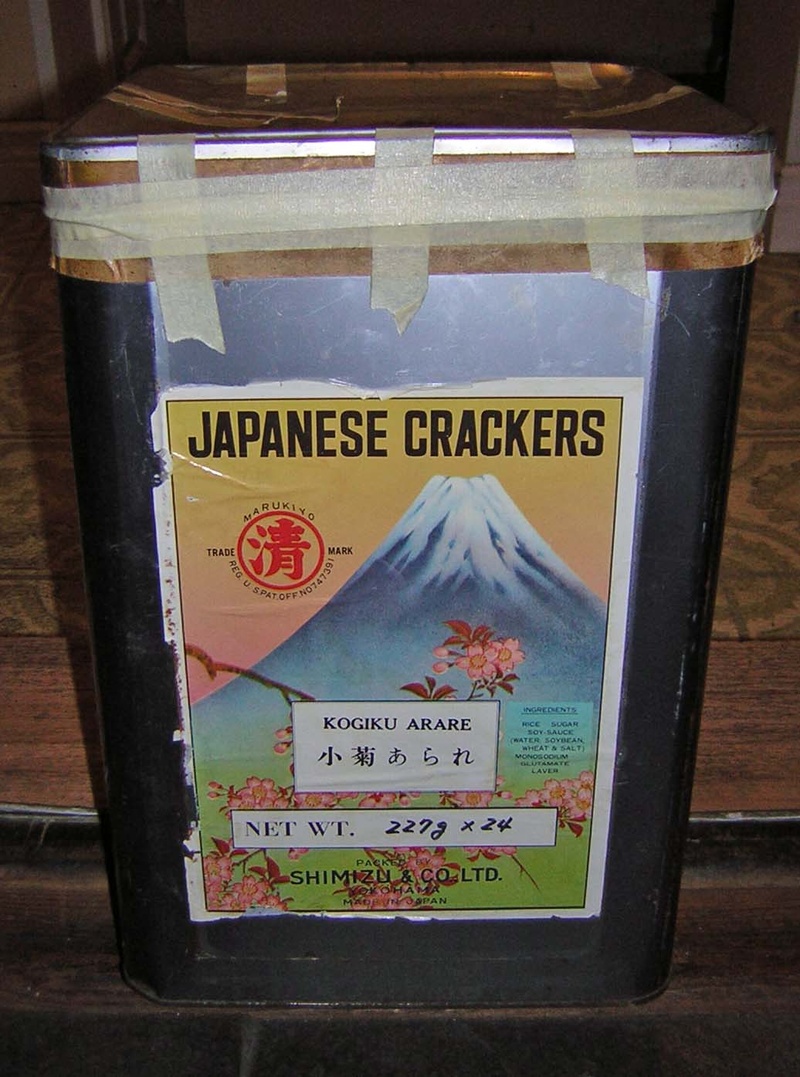

Families were provided with small garden plots, especially for those who lived in the old hotels. BC Security Commission most likely provided this land because the old folks used to call it ‘Commission Garden’ or Ko-mi-shon gah-den. The old tobacco cans were used as water sprinklers. Men poked holes on the bottom of the can with a large nail. A narrow stick about a yard long was pushed through small openings on either end for a handle. A large pail was probably an old senbe container. They carried a large bucket to their plot and scooped the water with this tobacco can that sprayed the water onto the vegetables. Boundary Creek in Greenwood was right next to Commission Garden.

Jeans were not hemmed so that a child could wear them for many years. A child would start off with a four-fold and by the time he got older, it was a two-fold job. If a child’s jeans were ripped at the knees, they were sewn together or had a patch put over it. Now days, girls spend over $100 to buy jeans that are already ripped at the knees!

Shoes and runners were worn till there were holes. If a heel came off, the shoe repairman would fix it and then put a metal plate on it so it wouldn’t wear down. If the toe part split often and looked like a smiling whale’s mouth, no problem, it would be stitched and be good as new! You have heard Dolly Parton’s song, Coat of Many Colours? Well, every piece of material was used to make a coat. Nothing was wasted.

Some families were fortunate enough to have chickens. The coop was made out of slabs or wood found at the mill. Chicken laid eggs for breakfast and later became a Thanksgiving feast. Children went fishing and brought them home for dinner. Green tea was made of niwatoko or saya endo. Tsukemono for some families were made from watermelon rind. Dandelions were used to make sake. Mushroom, huckleberry, Saskatoon berry, wild raspberry, and strawberry picking were a seasonal tradition.

When grandkids complain that their Nisei grandparents are “hoarders,” they will now know the reason. Have you seen your grandparents use scissors and dissect a toothpaste tube and scrape the last little bit of paste? Do you see little bits of soap in a ball? How many restaurant breakable chopsticks, plastic spoons and forks do you find in their utensil drawer? Also, are restaurant ketchup and soy sauce packets generally found in your grandparents’ fridge?

As you can see, Nisei had the word mottainai pounded into them. That’s why it’s so hard to let go of old habits of saving items that are not relevant in modern days. However, the “buzz” words today are recycle, reuse, and reduce. Well, I think the Issei and Nisei did that out of necessity for many years.

Nobel prize recipient and environmentalist, Wangari Maathai, was so impressed with the word mottainai that she popularized it world-wide.

*This article was originally published in the Geppo The Bulletin: a journal of Japanese Canadian community, history + culture, July 2016 issue.

© 2016 Chuck Tasaka