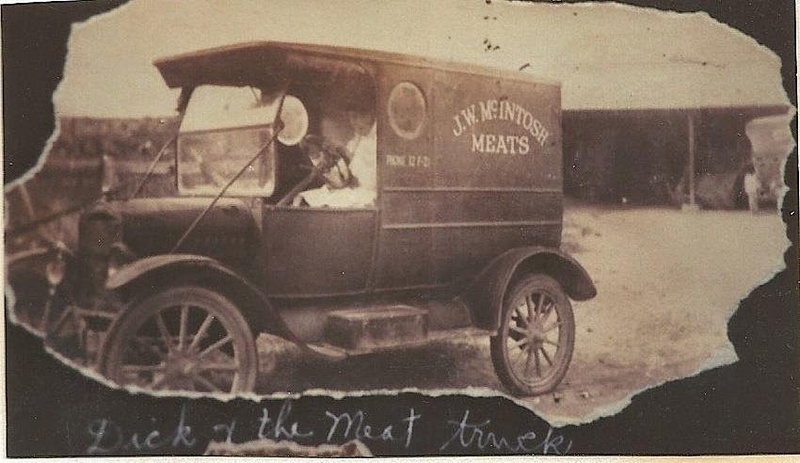

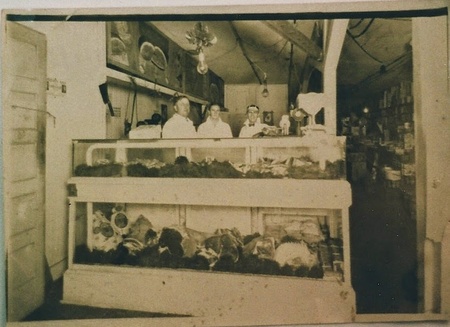

She bought Japanese food from (Tashima market)…there was a meat market owned by a hakujin, MacIntosh Meats. So, she bought meat from them. Those were the only stores around here. There were no other stores.

—Yukiko Yajima Furuta, Issei Experience in Orange County, California,

California State University Fullerton Japanese American Project,

Arthur A. Hansen and Yasko Gama, 1982

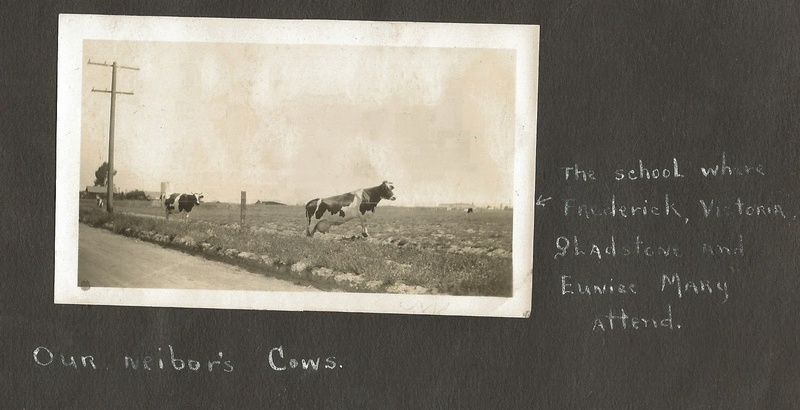

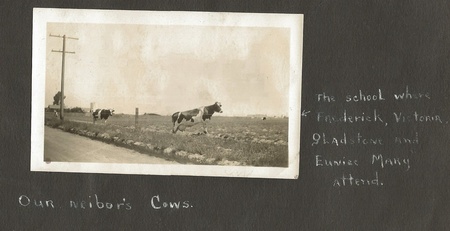

Wintersburg Village wasn’t just a farming town. It was also a cow town.

Once part of the Rancho la Bolsa Chica, cattle had grazed the fields and “little pockets” of grass in the wetlands for generations. When French aviator Hubert Latham made his infamous duck hunt by plane over the Bolsa Chica wetlands in 1910, farmers complained the cows spooked and scattered in the fields. With the railroad, the countryside in and around Wintersburg Village was a perfect place for an enterprising business focused on beef and dairy cattle.

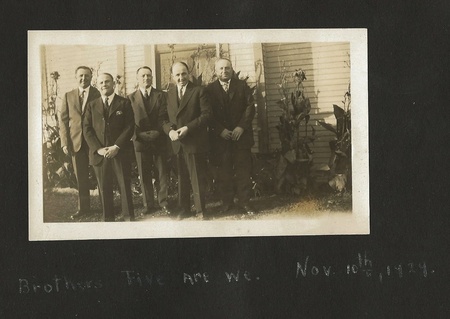

John William “J.W.” McIntosh made his journey to California from his birthplace in Prince Edward Island in eastern Canada in the early 1900s. A century before, the “MackIntosh” family crossed the Atlantic from the Isle of Skye, Scotland. Like many families who put down roots in Orange County, the McIntosh family was looking for open land, opportunity, and a place to create a promising life for their children.

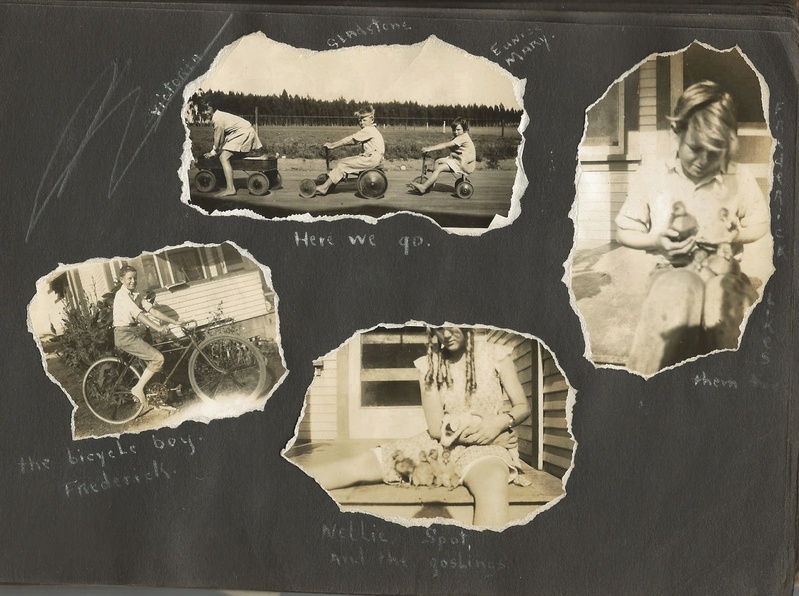

By 1909—the same year Huntington Beach incorporated as a city and the same year construction started on the Wintersburg Mission—J.W. McIntosh was running a butcher shop in Bishop, California. It was there he met Californian Eunice May Adell Baldwin. A 1975 McIntosh family history reports J.W. McIntosh gave Pasadena-born Eunice an “ultimatum: that he must be married by his 33rd birthday, or he would never marry.” They married in 1912, the same year Charles Furuta met and married Yukiko Yajima.

After a brief period running another butcher shop in Santa Monica, California, J.W. and Eunice McIntosh made the move to a growing Wintersburg Village in 1922, where they would raise their family.

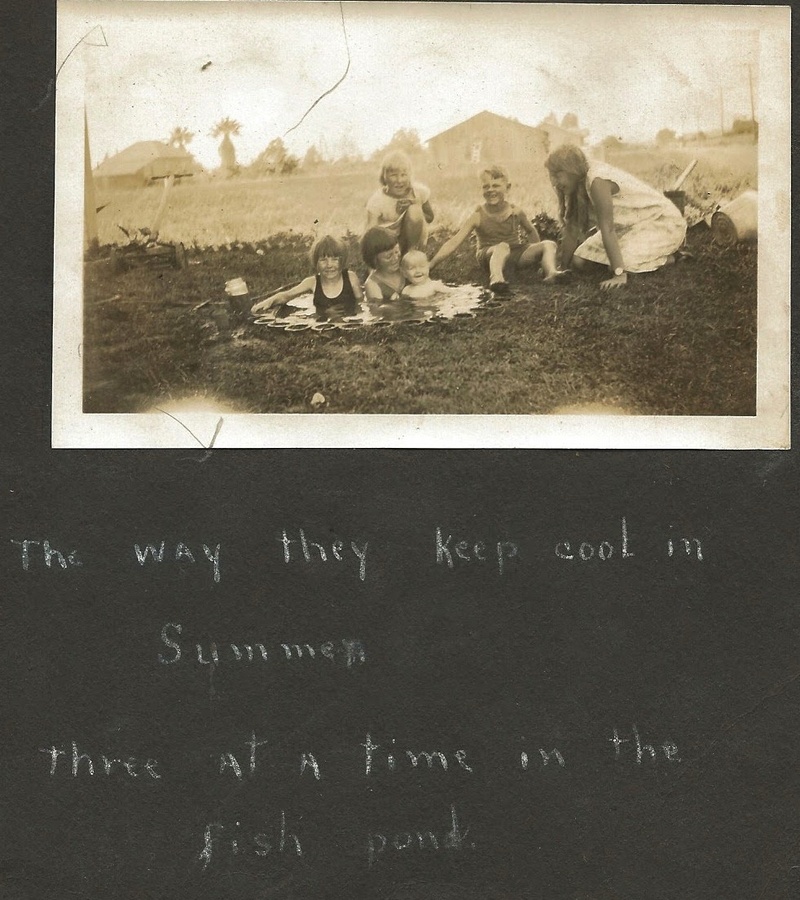

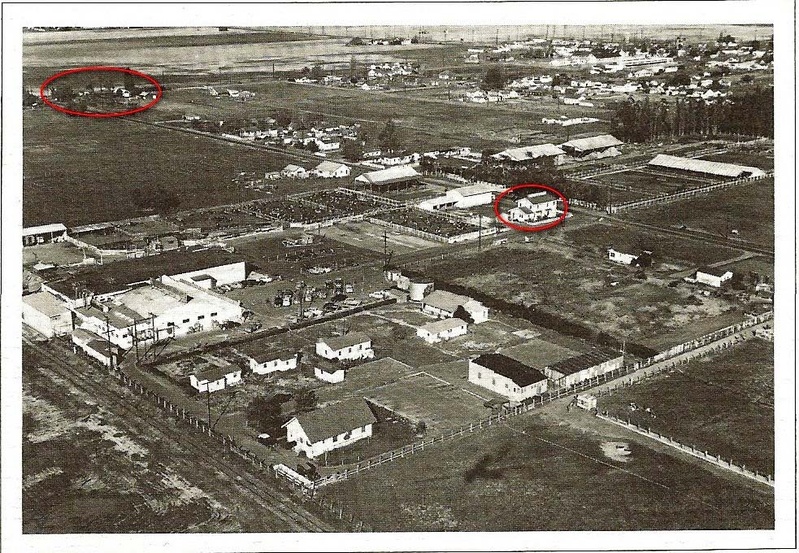

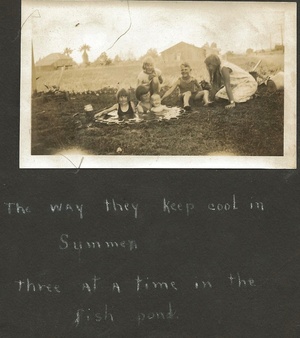

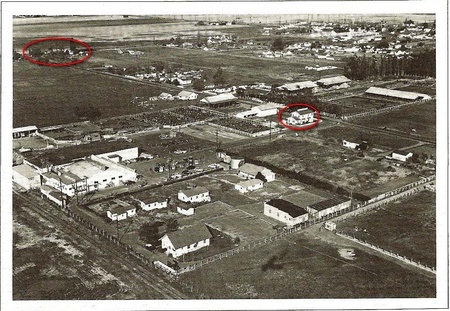

In the 1920s, Wintersburg Village boasted two churches, an armory, a railroad siding, blacksmith, the Tashima Market, a sandlot baseball field for Orange County’s first Japanese baseball team, and lots of open farm and grazing land. Charles Furuta had already tested out goldfish farming and the glittering fish were beginning to cover the five-acre Furuta farm in neatly organized ponds.

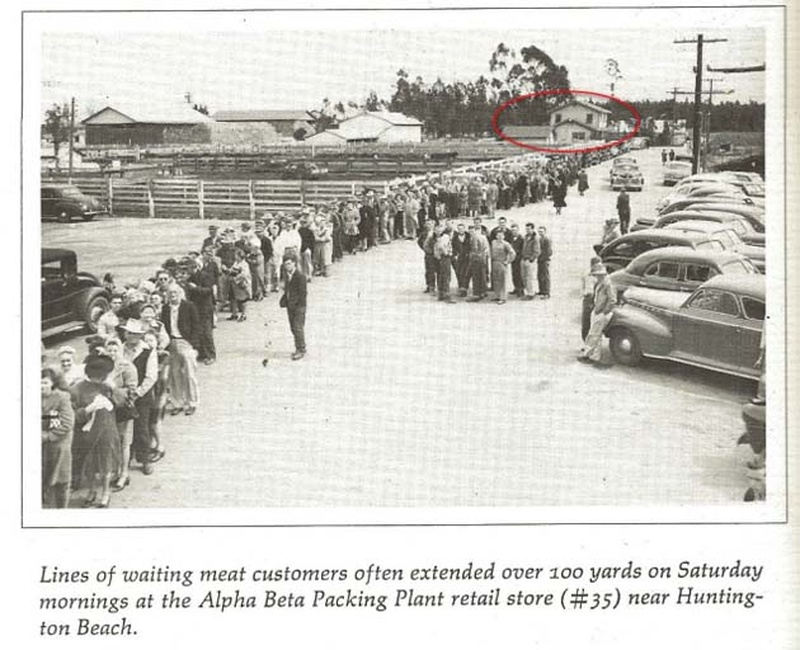

J.W. and Ray McIntosh established themselves in downtown Huntington Beach, with a meat department in the Standard Market at 126 Main Street. Unique for its time, the Standard Market was an open air building, with state-of-the-art refrigeration, the popular Rainbow lunch counter, and the Harris homemade candy store.

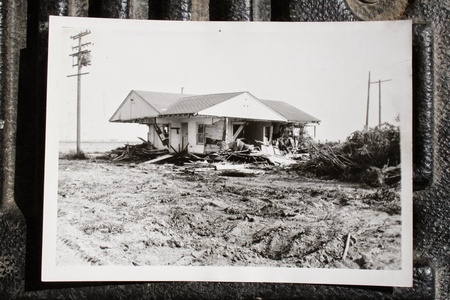

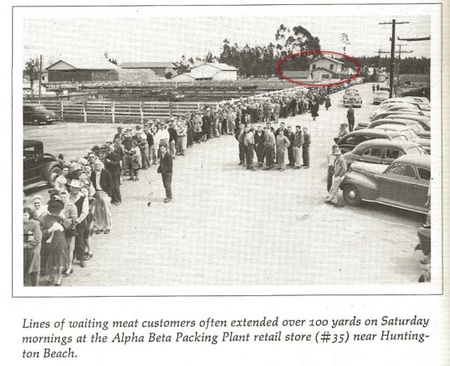

J.W. McIntosh also bought land in Wintersburg Village, off Nichols Lane, for a beef slaughter house and the Beach Packing Company facility next to the Southern Pacific Railroad. The McIntosh home and cattle yards were within easy walking distance from the Furuta farm and Wintersburg Mission.

It was at the Wintersburg packing plant that the McIntosh family sold meat to their farm neighbors, as remembered in the 1982 oral history of Yukiko Furuta. Descendent Norman Furuta recalls beef was often on the menu at home, as both his grandfather, Charles, and his father, Raymond preferred it.

Buying beef for the evening meal would have been a few minutes walk along the farm fields on Nichols Lane for Yukiko. With cattle lots out back, it didn’t get any fresher.

Near the McIntosh family ranch and home, were the Nichols family at Wintersburg (Warner) Avenue and what is now Nichols Lane, the Furuta family, and a host of neighbors from Mexico, Japan, Iowa, Georgia, and Kansas, according to 1940 data for their census tract. J.W. and Eunice McIntosh raised eight children at their home in Wintersburg Village.

In the 1960s, when Alpha Beta decided to open on Sundays, J.W. McIntosh, a religious man, retired.

McIntosh family descendent Douglas McIntosh has remarked on the influence of their Japanese neighbors on his family.

“My family has personal ties to the Historic Wintersburg community,” wrote Douglas McIntosh in his 2013 letter to the Huntington Beach planning commission, noting his great grandfather J.W. McIntosh also was an immigrant. “Members of my family had extremely positive memories of the Japanese community at Wintersburg. One of my great uncles learned to speak Japanese from members of the Wintersburg community during his youth, and later went on to become a linguist.”

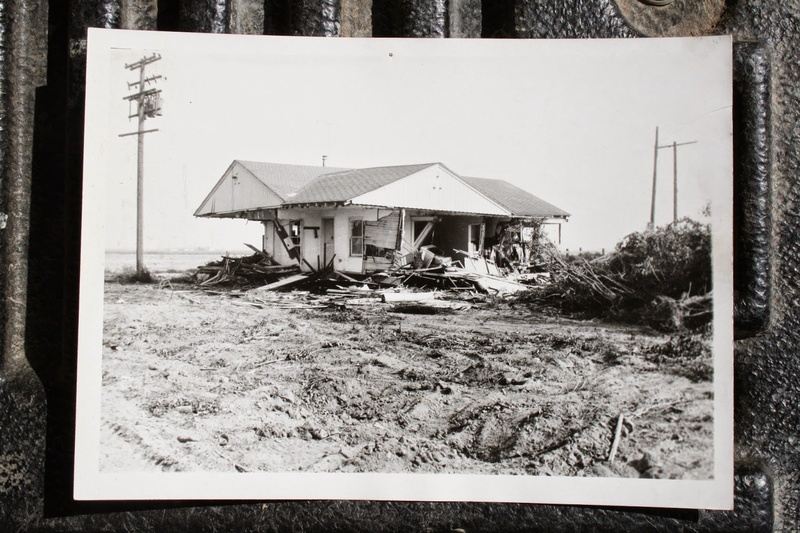

John Baldwin McIntosh, the great uncle of Douglas McIntosh, took an interest in Japanese culture and language, credited to his childhood in Wintersburg. He later attended the Los Angeles Baptist Theological Seminary, afterwards continuing to work at the packing facility in the 1930s with his family in Wintersburg Village. The packing facility and cattle lots by then had become part of the Alpha Beta chain.

In a 1975 family history, John Baldwin McIntosh recalls his wife, Genevieve, “liked to garden and I liked to continue my study of Japanese.” He and Genevieve later went on to do mission and linguistics work with Huntington Beach’s Wycliffe Bible Translators, including remote work with the Huichol Indians in Zacatecas, Mexico.

Like his great uncle, Douglas McIntosh, an archaeologist, also was influenced by growing up with the Japanese community.

Doug McIntosh’s branch of the family had moved to nearby Garden Grove, California. He was familiar with the Garden Grove Language School supported by the Wintersburg Mission as well as the Kikumatsu Ida tofu-making shop on the Language School property. Doug attended school with an Ida family descendant, whose ancestors had delivered tofu by horse and wagon in north Orange County as early as 1914.

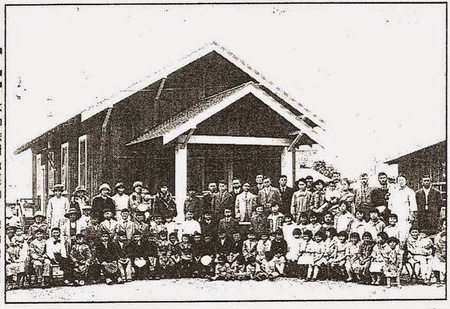

An Orange County Register article in 1991 quotes Phyllis Nakagawa whose children attended the school describing the school’s historical presence, the wooden desks with iron legs. Kumiko Swearingen described the loss of heritage. To her, the pioneer school had “a sense of home…at the new place we cannot touch anything. It’s not our classrooms.”

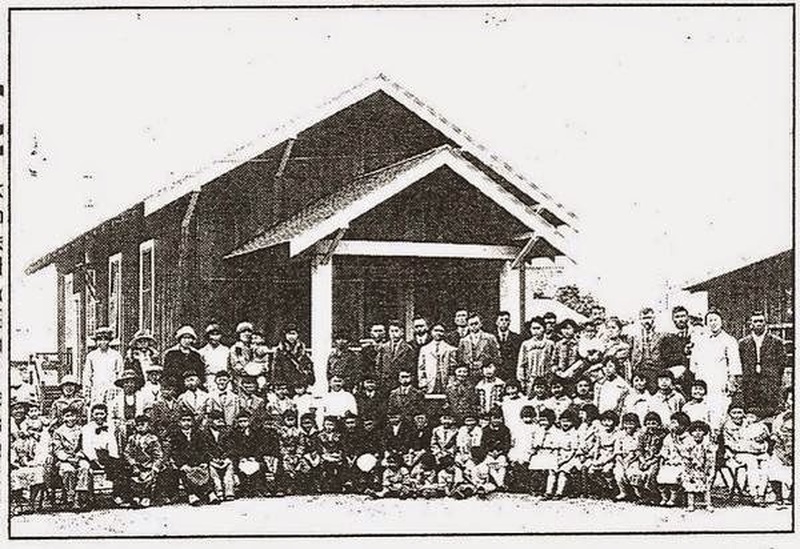

Built by Japanese pioneer farmers, the Garden Grove Language School organized in 1905 and graduated its first class in 1914. The Los Angeles Times in 1991 described the Nihongo Gakuen as “one of the nation’s oldest Japanese-language schools.” It represented both the County’s cultural heritage and an achievement as the first Japanese language school project in Orange County and most of the nation.

When the Garden Grove Language School was threatened with demolition for redevelopment, Doug McIntosh was a voice for its preservation, as was the Garden Grove Historical Society. The school’s demolition by the City of Garden Grove in December 1991—counter to the pleas by the Garden Grove and County historical societies, and the Orange County Historical Commission—is something he doesn’t forget.

Among the letters to Huntington Beach officials advocating preservation for Historic Wintersburg, are letters from Doug McIntosh. He speaks as an expert on California history and archaeology, and also as a member of one of Orange County’s pioneer families with ties to Historic Wintersburg.

“…in nearly thirty years of doing professional archaeological work at several hundred archaeological sites throughout the state of California, I consider the Japanese Mission Complex and Furuta Site to retain a high level of integrity and to be extremely significant on a local, state, and national level,” states Doug McIntosh in his 2013 correspondence to the City of Huntington Beach.

“Because of the overall urbanization of southern California no other sites such as this remain,” explains Doug McIntosh. “(It has) great historical value for not only members of the Japanese American community, but for researchers and general public of early California pioneer history.”

*This article was originally published on Historic Winterburg’s blog on March 8, 2015.

© 2015 M. Adams Urashima