Hitoshi Sameshima was born in Pasadena in 1921 to parents from Kagoshima, Japan. He was a junior at the University of Southern California when the war broke out in 1941. During WWII, his bilingual skills forced him into an uncomfortable position between Japan and the U.S.

By 1942, he and his family were incarcerated at Gila River. He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1944. Upon joining the Military Intelligence Service, which mainly consisted of Nisei linguists, Hitoshi was sent to the Philippines, where he was ordered to interrogate Japanese prisoners of war. “I knew the names and home addresses of the POW,” Hitoshi recalled. “So I felt like telling the families in Japan that their sons were alive. But I could not.”

WWII took the lives of many of Hitoshi’s friends. From then on, he felt strongly that war should be avoided if at all possible.

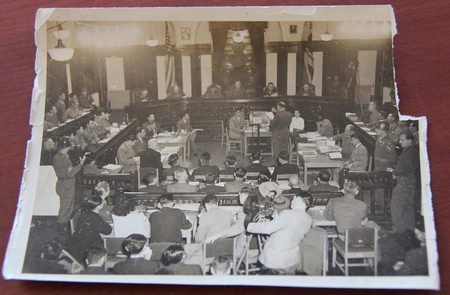

Even after the war ended, Hitoshi continued to find himself in that impossible place between countries, between languages. Stationed in Japan as part of the U.S. Occupational Forces, he was assigned to the 8th Army Judge Advocates Section and worked as a translator for the class B and C war crime trials in Yokohama.

There were several trials he could never forget. During one trial, he found himself wanting to help the defendant, a former Lieutenant Commander of the Japanese Navy, so he researched late into the night at the Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. When the case ended, the Lieutenant Commander sent Hitoshi a letter to thank him for extending his help, despite the fact that the men were “enemies.”

Hitoshi also remembers working on the Kyushu Imperial University vivisection case, in which the Imperial University medical department was charged with conducting vivisection experiments against American POWs. Five of those charged were executed and 18 were convicted.

For Hitoshi, this case stood out as the only one involving female defendants. One was the chief nurse; the other was a young girl around 18 years old. Hitoshi noticed that the younger one’s whole body was shaking. Hiding from the judge, he scribbled a note in Japanese on one of his papers and subtly flashed it to her. “It will be over soon,” read the note. “Hang in there.” Her shaking stopped and, after her testimony, she looked at Hitoshi and bowed deeply. He recalled, “This trial required not only legal terms but medical terms. I always had to use a dictionary. I had a hard time.”

During his stay in Tokyo after the war, Hitoshi met his future wife, Utako. It was love at first sight. Utako used to wear monpe (long pants usually for field workers) and a sweater, so when Hitoshi gave her a dress shipped from the U.S, she was delighted.

They decided to get married in Tokyo before Hitoshi’s assignment was over. His parents told him, “First, you should come back to the U.S. by yourself. If you still want to marry her, then you should go back to Japan.” But Hitoshi didn’t listen to his parents. He didn’t have time to buy a wedding ring. The two went to the U.S. Consulate, bringing Utako’s father as a witness, but he was not allowed to enter the building. Instead, a typist at the consulate had to serve in his place.

The couple moved back to the U.S. Utako, who was a Tokyo native, had a hard time communicating with Hitoshi’s parents, who spoke the Kagoshima dialect. “She was sweet and beautiful,” Hitoshi said with a smile.

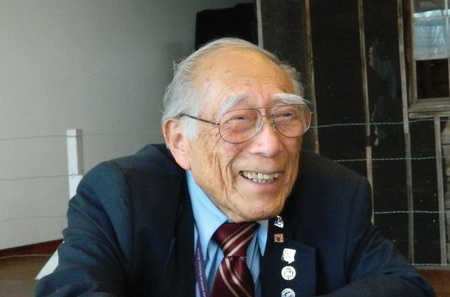

Later in life, he joined various organizations for veterans. He served as president of the MIS Club of Southern California, participated in the Southern California Community Committee of American Heroes, rode in the Korean War Veterans’ float at the 2013 Rose Parade—and even threw the first pitch at Dodger Stadium for the 2013 Japanese American Community Heritage Night. He also marched in the parade at the Nisei Week Festival which is held in Los Angeles every summer.

After serving Los Angeles County for 38 years, Hitoshi began volunteering for the Japanese American National Museum in 1990.

He was inspired by the late Akio Morita, co-founder of Sony and recipient of the Japanese American National Museum’s Medal of Honor in 1996, who said that “while most Japanese tourists came to Los Angeles for the shopping and sightseeing, they needed a place to go to learn about the hardships and sacrifices of Nikkei communities. I would like you to be a bridge between US and Japan.” Hitoshi, who had dual citizenship* and lost five friends in the war, thought “I have to pass on the Nikkei experiences, who fought for their country at the risk of their lives, to the next generation.” (*Nisei who were born before 1924 were allowed to have dual citizenship.)

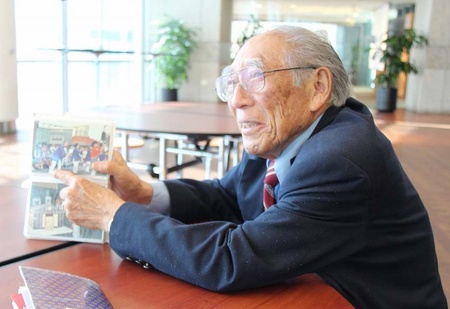

At the Museum, rather than being torn between countries, Hitoshi was able to use his language skills to bring Japan and the U.S. closer together, by guiding American and Japanese groups alike through the exhibitions. Over the years, he also led guided tours with Japanese VIP guests, including Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko of Japan, the late Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi, and former astronaut Chiaki Mukai. Hitoshi also spoke about his wartime experiences at numerous JANM panel events to pass on the Nisei legacy to the next generation.

A few years ago, when his niece asked him to name the three most important achievements of his life, he answered without hesitation: graduating from college, serving his country in the military, and participating in his many volunteer organizations. Hitoshi received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2012.

Because of his kindness and integrity, Hitoshi was a hero and an inspiration to many of his fellow volunteers and community members. Though he passed away on May 15, 2014 at the age of 93, his memory remains.

* Hitoshi Sameshima was interviewed by Alice Hama and this article was written by Ryoko Onishi for Voices of the Volunteers: Building Blocks of the Japanese American National Museum, a book presented by Nitto Tire and published by The Rafu Shimpo. This story has been modified slightly from the original.

Presented by

© 2015 The Rafu Shimpo