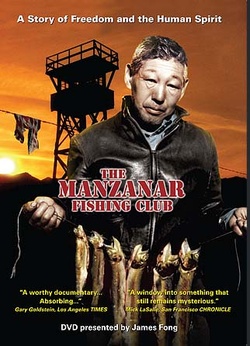

In 2004, The Los Angeles Times published an article about a mysterious man, identified only as “Ishikawa, Fisherman,” taken at the California World War II U.S. government prison camp Manzanar. Included in the story was a photo of Ishikawa, his face weathered and brown, holding a line of what article identified as “trophy size” golden trout.

Cory Shiozaki, a Sansei and avid fisherman, read the article—which singled out this photograph from an exhibit of works by camp inmate and photographer Toyo Miyatake—and was immediately struck. He knew that golden trout are only found above 8,000 feet, and nowhere near the 3,700-foot elevation of Manzanar. “It triggered my imagination,” Shiozaki, a television cameraman, says. “It became a very big mystery—how did he get the fish? I wanted to find out more about this guy.”

So began an eight-year investigation into the story of a group of inmates who defied authority and asserted their independence through fishing. Breaching the barbed-wire confines of the concentration camp, they turned the humiliation and shame of their illegal incarceration into rebellion-tinged idylls in the desert scrub, alpine regions and even above the tree line of the Eastern Sierra.

The culmination of this project was the March 2012 release of Shiozaki’ film The Manzanar Fishing Club, the first documentary about one of the ten World War II U.S. government incarceration camps to be screened in theaters. The movie was released on DVD in November.

Cory Shiozaki accepting Cherry Blossom Festival of Southern California's "Camp Stories Award" 2012. (Photo courtesy of Cory Shiozaki)

For Gardena, California-based Shiozaki, the project was a way to educate himself about a dark chapter of Japanese American history. Although his mother had been imprisoned in Topaz, Utah and his father at Minidoka, Idaho, like many Nisei they spoke little about the wartime hardships they endured. When their son learned about the mass roundup and incarceration at age 19, he decided that one day he would tell this Japanese American story. Thirty-six years later he found his angle.

The filmmaker had a job and a passion that accommodated his project well: From August to March Shiozaki works on various Hollywood television productions; during the industry hiatus, he lives in the Eastern Sierra, not farm from Manzanar’s location 230 miles northeast of Los Angeles, catching trout and working as a fishing guide. While working on The Manzanar Fishing Club, he used part of his time in the mountains to conduct research at area museums and libraries.

From the very beginning, he received help from Manzanar park ranger Richard Potashin, who collects oral histories from former inmates. Potashin passed off leads gleaned from his interviews to Shiozaki, and even let him tag along on some. Still, it was slow going, made more difficult by the fact that Issei and Nisei are generally not given to talking about their prison camp days. For the first three years the photo of Ishikawa was the only evidence Shiozaki had that prisoners went fishing.

Shiozaki also wasn’t sure what he would do with his research, he simply felt a burning desire to find out how it was possible that inmates could have traveled as far as 15 rugged, mountainous miles to find golden trout. In 2005 he became a docent at the interpretive center, where he created a lecture, exhibit and walking tour on fishing at Manzanar.

Shiozaki developed a lecture, exhibit and walking tour on fishing at Manzanar. (Photo courtesy of Cory Shiozaki)

Then a break came in the form of an October 2005 article on Shiozaki’s Manzanar fishing project in the Rafu Shimpo, which sent him in a new direction. Filmmakers Lester Chung and John Gengl of Torrance-based Talk Story Inc. saw the article and contacted Shiozaki to ask if he had considered making it a film. They joined the project, along with Shiozaki’s childhood friend, journalist Richard Imamura, who served as the film’s writer.

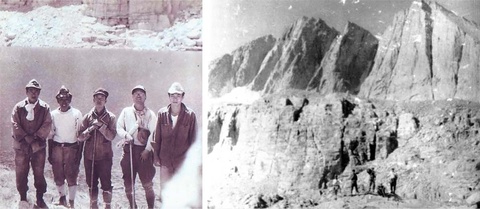

Meanwhile, Shiozaki had begun to locate sources. The first was Jiro Matsuyama, who worked as supervisor of Manzanar’s reservoir, a job that offered the perfect cover to escape for fishing expeditions. Next, a Sansei named Don Hosokawa from Long Beach came forward with family photographs that had been tucked away in the attic for years. “People never told these fishing stories outside of the family,” explains Shiozaki, it would happen after Thanksgiving dinner, ‘Remember when dad used to go fishing in camp,’ real casual.”

One by one, fishermen identified others, and Shiozaki and Potashin’s legwork began to pay off. One of the surprising discoveries they made was that Archie Miyatake, son of famed Issei photographer Toyo Miyatake (who took the photograph of the man with the golden trout), was one of the inmates who broke out of the prison camp to fish.

Archie Miyatake voices the central theme of The Manzanar Fishing Club when he refers to the “feeling of freedom” the risky fishing forays provided. He and his friends would slip out of the prison camp during the cover of night (through brush-covered holes they had dug earlier) and walk three to five hours in pitch dark to their chosen fishing spot. “It was really a satisfying feeling because you felt you put one over on the government,” Miyatake says in the film.

Writer Richard Imamura recreated a fishing pole made by prisoners from a repurposed kendo stick. (Photo courtesy of Cory Shiozaki)

There were even a few women who fished as well: Tami Takeuchi’s camp truck driver husband hid her under an army blanket in his truck and smuggled her out. Skilled fisherman Amos Hashimoto walked nearly six miles and climbed over 12,000 feet directly up Mount Williamson to fish pristine lakes located over two miles above sea level. The most amazing story is that of Heihachi “Joe” Ishikawa, the man whose photo ignited Shiozaki’s imagination. Already 53 when he arrive at camp, Ishikawa spent two weeks fishing at elevations over 8,000 feet, returning with the ultimate trophy, a string of beautiful 20” to 22” golden trout. His pride, notes his grandson Dale Ishikawa in the film, is evident on his face.

Though primarily concerned with the illicit pleasure of fishing, The Manzanar Fishing Club is filled with poignant asides. Matsuyama, who had a job in the defense industry before being imprisoned, volunteered to arrive at Manzanar early to help build the barracks that would house inmates. He drove his brand new Pontiac, which he was told he could keep, only to have it confiscated when he arrived.

The long hours Shiozaki spent interviewing former Manzanar prisoners has led him to related projects, such as volunteering for the Hanashi oral history program of the Go for Broke National Education Center. He adds, “I could honestly say if I died today I fulfilled my dream of making a film about the story my parents never told me.”

Search party for lost fisherman Giichi Matsumura, who perished after begin separated from the group. (Photo courtesy of Don Hosokawa)

* * *

FILM SCREENING

The Manzanar Fishing Club by Cory Shiozaki

Saturday, April 20, 2013 • 2PM

Japanese American National Museum

Los Angeles, California

Q&A to follow with filmmakers.

The film is available for purchase through the JANM online store >>

© 2013 Nancy Matsumoto