The taiko soul meaning is:

'the confirmation of our vitality and the cry of our soul';

'sharing feelings with others';

'reciprocal stimulation and encouragement'.

Daihachi Oguchi (sd: 4) 1

Preliminarily, it is worth highlighting that organology is the study on the ground ( sueokigata ) of musical instruments, focusing not only on the structure and possibilities of the instrument, but also on its geographic, historical and socio-cultural surroundings.

The taiko is among the most widespread and played instruments outside of Japan. In Brazil, since the vogue of the Olodum – without intending to point it out as a cause – I have noticed a proliferation in adherence to the “soul of the taiko”, especially among young people, which, as can be inferred from Professor Oguchi's expression, before being a musical option, it is a life attitude. It is necessary to emphasize that he was “the introducer of the multiple collective system [group of varied taikos], in 1951” (op. cit.: 6), in the post-war historical context. Thus, the words “vitality, sharing, stimulus and encouragement” strongly reflect the spirit of rebuilding the self-esteem of a country half-destroyed by the second war. Today, according to London ethnomusicologist David Hughes 2 (1983: 501) “these taiko 'orchestras' play the role of generating the spirit of the village or town”, that is, of local identity, a feeling of collectivity and belonging.

The term taiko is spelled with the kanji (ideograms) 太tai , supreme, and 鼓ko drum, designating drums in general, especially the membranophone, whose main vibrating element is a leather membrane. When the term is a suffix, it becomes daiko , as for example, wa-daiko和太鼓, for all national drums, tsuri-daiko , for all hanging drums, 大太鼓, ō -daiko , for the big drum,平太鼓hiradaiko , for the cylindrical drum, nodaiko , for the drum used in theater, among others. The most common types are 桶胴太鼓okedō-daiko , and 締め太鼓shime-daiko .

The isolated reading of the ideogram 鼓, ko , is tsuzumi , another generic name given to Japanese drums, or specifically, it is the drum of the theater ensemble in , which is played with the instrument resting on the performer's right shoulder. The ideogram ko presents on the left side the kanji yorokobi , joy. That's why taiko teachers usually recommend that the student enjoy the joy of playing, transmitting this joy to the spectator.

Most Japanese drums have a membrane at each end of the body: one for playing and the other for resonating or ringing (by the same percussionist or someone else). These skins are usually bovine or equine. The resonance box or “body can be made with different woods, zelkova, sandalwood, pine, cherry, etc.” (Hughes 1983: 501). With the exception of the hiradaiko and shimedaiko , which have a straight cylindrical body, all taiko have a barrel-shaped body. Unlike the tsuzumi鼓, an hourglass-shaped body, whose coltskin is struck with the fingers, all taiko drums are struck with drumsticks called bachi .

There is a wide variety of diameters and lengths among double-membrane drums, the largest of which are found among the ?-daiko, tsuridaiko and hiradaiko . But the main difference lies in the way of attaching the leather to the body or ring: in barrel-shaped drums, the skins are attached directly to the body using tacks; In cylindrical or hourglass-shaped drums, the skins are attached to a hoop with a diameter larger than the body, and are generally tuned by tightening the strings tied to the hoops. In this type of hoop, in addition to the okedō-daiko , we have the dadaiko , used in gagaku court music, the kakko , used in the nagauta, the shimedaiko , in no theater and daiby?shi , in folkloric manifestations.

Taiko can be played in different positions and angles.

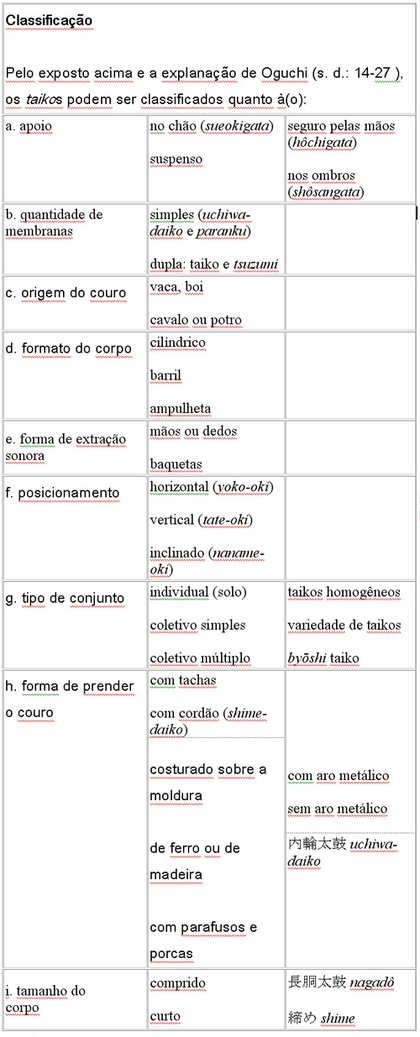

CLASSIFICATION

Based on the above and Oguchi's explanation (sd: 14-27), taikos can be classified according to:

USES AND REPRESENTATIONS

The oldest records of taiko found in Japan, from two thousand years ago, were in the vicinity of Lake Nojiri and Togariishi ruins. As the first region was full of elephants, it is assumed that the instrument was used to be played, while the hunter made screams to attack them. In the second location, “clay pieces were found, where it is assumed that they were covered with leather [..] serving as a tool for exchanging goods”, continues Oguchi (sd: 3), inferring that the ancestors used taiko to distance communication and express feelings of joy, anger, sadness and pleasure.

As it was an essentially rhythmic instrument, it served to homogenize the soldiers' march and, in some regions of the country, the tradition of announcing the time of day for the village still continues. Oguchi (sd: 5) highlights that to understand the origin of many current ringtones:

we cannot ignore the jindaiko , war drum, which the commanders of the war era invented with the intention of conquering and bringing out the mystical force that the taiko possesses to raise the morale of those they command, [...] with the purpose of elevating the spirit and stimulate the courage of combatants during war, eluding and scaring away enemies.

The entry “taiko” from Wikipedia 3 reinforces its military use:

In feudal Japan, taikos were often used to motivate troops, to help mark pace in marching, and to announce commands and martial clashes. When approaching or entering the battlefield, the taiko yaku [drum beats] was responsible for determining the pace of the march, usually with six steps per drum beat.

According to one of the historical chronicles (the Gunji Yoshu ), nine sets of five knocks were used to lead a battalion into battle, while nine sets of three knocks were accelerated three or four times and followed by the shouts "Hey! Hey! O! Hey!" Hey! it was the call to advance and pursue the enemy.

After these remote assumptions of survival, we have reminiscences of the use of the drum as a religious instrument. In several cultures, the drum has the power of trance or enchantment, such as in shamanic ceremonies or Afro-Brazilian rituals, such as Candomblé and Umbanda. In Japan, taiko is also always present in temples, as it is considered the home of ancestors and gods, serving as an instrument of communication or connection with such supernatural entities. In mythology itself, there is a version that the drum served to attract the sun goddess Amaterasu – who had hidden in a cave and left the world in darkness, after being contradicted by one of her brothers – bringing back the light of day.

Nowadays, taiko is the protagonist of festivities or matsuri in various localities, as it is believed to serve to calm or exorcise disturbing or restless spirits.

It is estimated that the art of taiko was introduced when Japanese music was influenced by Chinese culture, via Korea, in the Asuka period, around the 7th century, shortly after adopting writing and Buddhism. Oguchi (sd: 6) adds:

The taiko acquired typical sounds and movements, becoming a musical instrument used in theater, especially in kabuki . From the Edo era [secs. XVII to XIX] was widespread in folk music. From then on, different styles of taiko emerged in other regions of the country, with different denominations alluding to the names of the respective places or the names of the festivities.

The professor also explains that taiko has already surpassed the frontier of folk tradition and, through its advancement in resources and timbres, has gained its place in contemporary and international artistic music.

Notes

1. Oguchi, Daihachi. No date. Taiko manual. Translated by Artur Nakahara. No location: Japanese Taiko Confederation, no date.

2. Hughes, David. The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. 3 vols. London: Macmillan, 1984.

3. http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taiko, accessed on November 26, 2007.

© 2008 Alice Lumi Satomi