Though I often focus on my grandfather’s acts of defiance and resistance when I talk about my family’s camp experience, the truth is that my dedication to family history — and the development of Tessaku — would not exist without my grandmother, Itsuye.

Since I was young, I was fascinated with the fact that the incarceration, set off by a string of incredibly complicated, global events, somehow found its way to impact our family so deeply. I knew that what my dad and grandparents, Tamotsu and Itsuye Tsuchida, went through was something major that haunted our family, as I would see how many books my dad had on the subject, the apology letter from President Bush framed on our wall, the collection of black and white photographs from the 1940s. It was something I knew I would return to, as it lingered in the back of my mind for years, through college and beyond.

What I could not have predicted is that it would take losing my grandmother to make Tessaku happen, opening a pathway to uncovering not only my own, but many others’ family histories.

My grandma was the grandparent I had in my life the longest, and though I could not communicate with her in any depth due to our language barriers, the love she carried for her son and her grandchildren was a testament to how family connection needs no fluency. A Kibei who was born in Los Gatos, California but educated in Fukuoka, she was quick to laugh and found everything funny.

When she would arrive at our house and I’d hug her on the driveway, the running joke between us would be me asking her why she was shrinking in height, and her laughing and hitting my arm. If my dad had to explain something serious or question why she did something she wasn’t supposed to, she would break into laughter, finding the humor in my dad’s frustration. Cards would always show up for our birthdays, and she never missed a holiday with us. She had a lightness that was a part of her being, and must have been present her whole life, as there is only one photo that I’ve seen of her when she is not smiling.

That photo was taken in Topaz, before she and my dad were taken to Tule Lake, alone, after my grandfather was arrested for being a protestor and “troublemaker,” which got him sent to the Citizen Isolation Center in Leupp, Arizona. Separated from her cousins in Topaz and with very little English fluency, I can’t imagine what she faced being forced to move from one camp to another, where tensions ran even higher.

When my grandfather reunited with them in Tule Lake, she was put through more strife and uncertainty, as my grandfather insisted that Japan was winning the war and they would go back. My father remembers her telling him, “You go, I’ll stay and raise Mikki here.” As fate would have it, they didn’t go to Japan but were once again alone after camp at the end of 1945 to early 1947, while my grandfather was held — indefinitely in their minds — in Crystal City, Texas.

My dad remembers that difficult stretch of time as my grandmother barely made ends meet with her house cleaning jobs. In the meantime, she wrote letters to the Attorney General asking for updates on her husband, when he might be released, and apologizing profusely for his behavior. In these letters — which had to be translated by a relative — she brings up my dad, writing that “the boy misses his father and wonders if he will ever return.

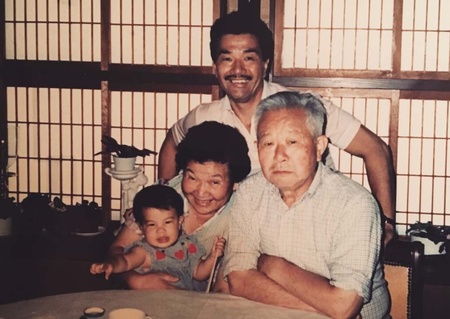

When she became a grandmother to four grandchildren, it must have given her new purpose in life. In my eyes, it was as if the camps never even happened to her, as she never brought it up. My grandfather, being 12 years older than her, aged much faster and focused much of his time on sharing and recounting what he went through in four camps. He died when I was eight, and I was much too young to really have known him.

But my grandmother was still very much a part of my life as I entered my 20s. A year or so before she died in 2014, her dementia was so severe that she forgot everyone in the family except my dad. “This is my son,” she would say, introducing him to us. She’d look at me and think that I was her niece. And when we would tell her that I was her granddaughter, she, of course, would laugh.

I was living in New York when I got the call from my mom that she had passed. I felt a deep, heartbreaking loss, immediately regretting the time I did not spend in the care home a little longer, or the check-in calls I never made, wondering how I found myself so far from home, working a job that at the end of the day, meant nothing to me.

Her death prompted me to move back to California and take a deeper look into everything our family went through. It took her death to understand how profoundly their experience of the camps had shaped me, and I needed to understand why.

I always wondered if the grandma we knew and loved was the same woman who faced and survived the incarceration. My dad and I have such deep regrets about the conversations that we should have had, that could have shed light on her point of view and filled in the gaps of family history and chronology where we find ourselves stumped. “I should’ve asked my mom more,” my dad often says to me.

I find myself missing her more as I get older. As I write this from Japan, I think about how wonderful it would be to tell her about visiting this amazing place. I see other Yonsei my age who still have their grandparents around, and I can’t help but feel a twinge of envy, wishing I still had mine to share my life’s milestones. But with her death, my grandmother left me one of the greatest gifts — losing her was the catalyst I needed to refocus and refine my purpose, to take seriously our family history, to unearth the effort and time that led to creating a project that I could not imagine my life without.

I wish that I could tell her today that she was the inspiration for a calling that I always knew was deep within me, and that it was her choices in those unimaginable years by herself with my dad that profoundly shaped him. How she went through all of it, and still made the choice to be happy.

And if she heard this, I’m certain that she would just laugh.

*This article was originally published in the Densho’s Catalyst on March 23, 2023.

© 2023 Emiko Tsuchida