Unique "Japanese Literature"

For second- and third-generation Japanese American or Canadian writers, the tragedies of Japanese people brought about by the Pacific War, such as the state's internment policy, have become major themes in their works, such as John Okada's No-No Boy, Joy Kogawa's Obasan, and Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was God.

Works related to the concentration camps in particular have come to be known as "concentration camp literature," and among these literary works there are many that convey strong social messages about the fight against racial discrimination and prejudice from the perspective of those who have had their dignity stolen, or who are, so to speak, victims.

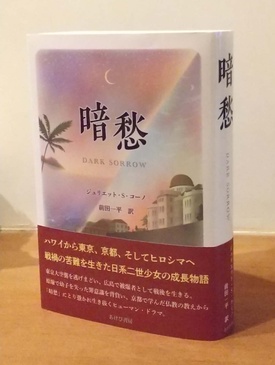

From this perspective, "Darkness" (translated by Maeda Ippei, Akebi Shobo), written by third-generation Japanese-American Juliet S. Kono, recently translated and published in Japan, is a unique work that depicts the life of a second-generation Japanese-American during the Pacific War. The Great Tokyo Air Raid, which killed 100,000 people in one night, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, which killed an estimated 140,000 people, are depicted. Discrimination, jealousy, bullying, betrayal, poverty. Although the story describes the life of the protagonist as she survives harsh realities, no social or political messages are immediately apparent.

The original title is "Anshu: Dark Sorrow." Although it is not a familiar word, "anshu" can be said to be the theme of this work. According to the dictionary I have, "anshu" means "sorrow tinged with a dark shadow" (Daijirin). The story is shrouded in low, dark clouds throughout. It is the sorrow that covers the dark times of war, but also the sorrow that dwells in people's hearts.

As the war worsens, the protagonist Himiko and her uncle's family are forced to flee their homes during the Great Tokyo Air Raid, and so they take refuge in a temple in Kyoto for a time. In a conversation with the monk there, Hara, the topic of "melancholy" is discussed. Hara says:

"Japan has truly entered the 'valley of darkness.' For us it is now a time of 'sorrow' -- that is, a time of melancholy." (Omitted)

In contrast, Himiko, who feels responsible for the death of her cousin Sa-chan, who had viewed her as an enemy, while fleeing from an air raid, perceives melancholy in a different sense.

——Melancholy. Melancholy. I muttered. Priest Hara spoke of the war, but I was drawn to something more personal. Something so deep and sad. My feelings about all the things I had done to others, especially to Sar-chan. Melancholy was mine, my being, the sadness and guilt I felt for those who had corroded my heart. I had found a name for it. ——

After a short stay in Kyoto, Himiko and her friends move to her uncle's hometown of Hiroshima, where they once again take refuge in a temple, this time being treated kindly by the head priest Seki. The story is full of expressions that suggest an underlying Buddhist view of things, such as impermanence and nothingness, including conversations with the monks, and the protagonist's heart moves and grows as it becomes intertwined with these teachings of Buddhism (Jodo Shinshu).

Hawaii-Tokyo-Kyoto-Hiroshima

The story begins in a community of Japanese people working in the sugar cane fields of Hawaii before the war, then moves to downtown Tokyo before the war, and finally to Kyoto and Hiroshima.

Himiko was born and raised as the second daughter of a poor Japanese family who immigrated to Hawaii. When she became pregnant at a young age, she was sent to live with her uncle's family in Japan. After giving birth despite the hardships of not being welcomed, she was forced to flee Tokyo, burned out by air raids, and traveled to Hiroshima via Kyoto. She was also exposed to the atomic bomb there, but she survived, but many of her close friends and family died during this time.

The war between Japan and the United States casts a complex shadow over the heart of Himiko, an American born in Hawaii who looks Japanese but has Japanese roots. As a result, she is hurt by both Japan and the United States, but ultimately she does not show any anger towards others.

After being exposed to the radiation and suffering serious injuries, Himiko even feels a sense of fulfillment in being able to help others. After the war, American doctors visit Hiroshima, and Himiko offers up her injured body to them, knowing that in the name of treatment they will treat the victims like living specimens of the atomic bomb's damage.

By accepting everything, including the regrets about one's past actions, one can feel freer in both mind and body, and even feel as if one has reached a state of enlightenment. This point is probably connected to the teachings of Jodo Shinshu.

Translators' efforts pay off

Author Juliet S. Kono is a poet and novelist. She is a third-generation Japanese American born and raised in Hilo, Hawaii in 1943. She graduated from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and completed her master's degree at the same university. During her time at university, she participated in the literary movement of the Hawaiian literary magazine Bamboo Ridge. She continues to write as a poet, publishing poetry collections Hilo Rains (1988) and Tsunami Years (1995). Anshu: Dark Sorrow, published in 2010, is her first full-length novel. She has received various awards, including the Hawaii Literary Award in 2006. She lives in Honolulu and is a Jodo Shinshu Buddhist priest.

The translator, Ippei Maeda, is a researcher of American literature and has translated the bestselling American novel, "That Day at the Panama Hotel" (Jamie Ford, Shueisha), which is set against the backdrop of the wartime history of Japanese Americans. He was born in Nakamura City, Kochi Prefecture (now Shimanto City) in 1953 and completed his doctoral studies at Hiroshima University Graduate School. He is a visiting professor at Central Washington University, a visiting researcher at the University of Washington, and a professor emeritus at Naruto University of Education. His books include "Young Hemingway: Searching for Life and Sexuality" (Nagundo) and "Hemingway Criticism: Thirty Years of Voyage" (Takanashi Shobo), which he supervised and co-authored.

This book vividly describes the devastation caused by the Great Tokyo Air Raid and the Hiroshima atomic bombing. It also touches on the Makurazaki Typhoon, which hit the Hiroshima area a little over a month after the bombing, and the damage it caused. According to the translator, Mr. Maeda, the author spent 10 years researching and writing the book.

Speaking of 10 years, it took Maeda 10 years from the time he got his hands on the original book until he managed to get it published in Japanese. He started translating without even having a specific publisher in mind, and after completing the translation he finally found a publisher, and the Japanese version of "Anshu" was born. We would like to introduce the background to this and the significance of this book in our next interview with Maeda.

* (For information about the author and translator, please refer to the profiles at the end of this book.)

© 2024 Ryusuke Kawai