In 1988, when Gene Oishi’s memoir was originally published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company, the camps had been closed for more than forty years. This was also the year that the Redress Movement achieved its greatest victory, with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 granting $20,000 in reparations for each camp survivor, as well as a presidential apology.

I was born in 1989, long after the camps, a year after redress and reparations. What was to Oishi a childhood trauma has been passed down to me as an inherited trauma. I was raised in the West Coast Japanese American community, where incarceration is a foundational moment become foundational narrative. As I’ve navigated my life, I’ve had no choice but to grapple with camp and its afterlives. This is especially true because camp stories, which continue to shape Japanese American identity, politics, and culture, have been repeated, manipulated, and updated across various genres, forms, and platforms.

Oishi’s book is, for me, an inheritance in multiple ways. Having been invited to take part as an editor in helping to present this story that began well before my birth, I’ve tried to discern what it means for me, a Yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese American), to be creative and commemorative in this particular moment. Above all I’ve had to consider how to be an effective conduit between generations. What are my responsibilities both towards Oishi and towards those who will come after me?

My hope is that Kaya Press’ revised edition of In Search of Hiroshi provides additional context to the particularities of Oishi’s Nisei story by including evidence of intergenerational reverberations. Introduced by new writing by Oishi and concluded by a joint paper presented by Oishi and his daughter Eve Oishi at an academic conference, this project provides an opportunity to consider the changing nature of the memory of incarceration across lifespans and generations. The scholarly and political frameworks at our disposal today have transformed our understanding of the camp experience.

Before reading In Search of Hiroshi, I thought I knew Oishi’s story. I was raised in what felt at times like an over-saturation of camp narratives, so much so that I was convinced I could analyze those experiences better than those who lived through them. The “camp story” felt to me like a genre whose broad strokes I could fill in myself. But Oishi’s memoir is the record of an individual working through decades of trauma: as such it can’t be reduced to broad strokes.

This became clearer to me the more I worked and talked with Oishi. For him, the possibility of working with a Yonsei editor is certainly one obvious change from 1988, when the Tuttle Company, which was founded by an American stationed in Japan during the war, was one of the few publishing options for Japanese American writers.

Some conversations revealed the assumptions I have from being raised in the bosom of the West Coast Asian American Movement. I was very surprised that he had never heard of the Day of Remembrance, the annual commemoration of the signing of Executive Order 9066, which originated in the 1970s as part of the organizing for redress and reparations.

It has since become a mainstream part of JA culture, observed by most individuals and organizations regardless of their politics. It was in moments like this that I began to have a more visceral understanding of what it meant for Oishi to attempt to escape his racial identity for so long.

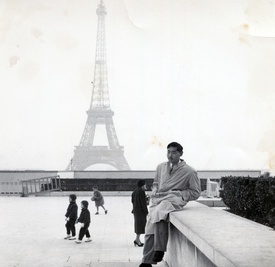

Choosing to live in Europe and on the East Coast, he removed himself almost completely from the JA community in his adult life. He noted that over the decades almost none of the reader responses to his articles or books have been from JAs. For Oishi, writing about and through trauma has often been a truly solitary process.

Other times, I felt the connection of our cultural identity more than our generational or geographic divide. Speaking to Oishi one day about the model minority myth led to a conversation about the many ways JA complexity is flattened, including within the community itself. I have found that many JAs feel alienated by the simplified narratives of who we are. What might it mean to recognize self-alienation as a shared cultural inheritance? And how can intergenerational conversation help to overcome that alienation?

Oishi began to experience the profound impact of connecting to the Sansei generation in the 1980s, when he traveled the country interviewing JAs for the assignment that would become “The Anxiety of Being Japanese-American.” Breaking his self-imposed isolation and “[s]eeing [his] own Nisei generation from across generational lines” was particularly transformative, even when it came in the form of blunt criticism. We laughed as I reassured him that the Sansei were now receiving their own fair share from my generation as well.

Yonsei and even Gosei (fifth-generation) scholars and activists are contesting and rewriting the meaning of not only camp but other “primal moments” such as redress and reparations. Japanese American identity is being considered through a range of new political and personal perspectives, aided by frameworks that take into consideration questions of diaspora and settler colonialism.

But even as a new generation of writers and scholars strive to deepen and broaden our understanding of the “camp story,” it also seems important to try to read between the fault lines that continue to exist between the generations. Oishi touched on this as well:

“The complaint I’ve heard from Sansei is that my parents just won’t talk about it. And they’re upset about that. Well, I did want to talk about it, but not to my children so much, but to the public in general being a journalist....”

Eve Oishi’s new introduction to their joint paper describes a different dynamic of familial disclosure, calling themselves “lucky to have a father who shared many details of his childhood, even if the sharing was part of a painful process of self-discovery that we were witness to.” Oishi’s search engendered their own, with scholarship born from “an attempt to trace the things that I knew and felt back to events from before I was born.”

Oishi’s memoir is thus an occasion to reflect on not only the impact of incarceration, but also the shifting nature of alienation across and between generations. For Oishi, writing was a long, lonely search for internal resolution. And at the same time, his story informs Eve Oishi’s, mine, and so many others in ways he couldn’t anticipate. At one point he commented to me that having lived through it, he has little appetite for analyzing incarceration’s aftermath. Its meaning for and impact on younger generations, even his own children, is not his story to tell. He told me, “That’s for you to write.”

Still, as the living memory of camps fades, it seems ever more vital to not let our contemporary readings—our post-memories—supersede completely those that came before. The evolving nature of “our” narrative and “our” identity is made and made singular in Oishi’s search. Over the course of a long life, the texture and transformations of silence and self-disclosure are lived and written differently. The richness of our bodies of literature, scholarship, political organizing, and the identities and communities they engender, are indebted to these kinds of records. For me, and for those who come after me, In Search of Hiroshi can be at turns a gift from an elder, to be treated with reverence, and an invitation to do with it what we will.

*This is an excerpt from the revised edition of In Search of Hiroshi by Gene Oishi (2024).

@ 2024 Ana Iwataki