Reaching a Turning Point

During the war, in a statement to Asia and the Americas, Tashiro described his family as follows:

Many years ago my parents came to Hawaii from Japan as immigrants to the Hakalan sugar plantation, managed by lovely Scotch people by the name of Mr. and Mrs. John M. Ross. I was born in Hawaii under the protection of the Stars and Stripes. My parents always sought to ensure my education as a good American citizen, insisting upon truthfulness and religion. They educated me entirely in American educational institutions. I thank God that I am an American citizen and am enjoying freedom, prosperity, good health, good music happiness, and lovely Christian friendships.1

In many ways, the above narrative indicates a change from Tashiro's activities as a Buddhist on the West Coast and in Japan in the 1930s and suggests a turning point in his spiritual beliefs. Could he have converted from Buddhism to Christianity just before the war broke out?

In fact, there is one event that might have led to Tashiro's turning point. In July 1940, Tashiro led twenty-four American college and high school students on an “inspection” tour of Japan, which was organized by an educational organization called the “Experiment in International Living.” The students stayed in Japanese homes for about four weeks; Tashiro led the high school group and Toru Matsumoto, a graduate of Union Seminary in New York and a well-known pastor, led the college student group.2

Tashiro must have converted to Christianity before summer 1940. He listed the Reverend Clarence E. Paulus as a close friend on the World War II registration conducted in 1942.

Marriage and Family

Tashiro moved out of the University of Chicago International House in 19413 and went to live at 6144 S. Kenwood Street,4 while retaining his dental office at 841 E 63rd Street until 1947.

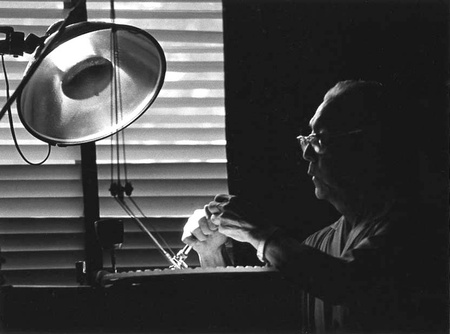

During the war, in 1944, Tashiro bought a house at 4429 S. Ellis Avenue in the prestigious community of Kenwood5 and moved his dental office and practice to the house around 1947.6 He made dentures and bridges in his own laboratory at the office, which he named the “Bei Nichi lab”7 a witty reversal of the term “Nichi-bei” (Japan-US).

In 1951, Tashiro married Kimiko Mukai, a Hilo schoolteacher who was born in 1909 in Laupahoehoe, in Hawai‘i.8 Kimiko was Christian and active in the Hilo Salvation Army as a member of the temporary women’s advisory committee.9 She had also worked for the Hawaiian Japanese Civic Association in the 1940s, on matters such as the 1941 annual membership campaign of the Association, with Dr. David Mitsunaga.10 It is unknown how Isamu and Kimiko met, but we might guess that Dr. Mitsunaga could have been the “go-between” for his senpai from the Chicago College of Dental Surgery.

The only article which reported that Isamu and Kimiko were even a married couple appeared in the April 28, 1953 Hawaii Times, and read as follows:

Dr. Isamu Tashiro and Mrs. Tashiro are scheduled to arrive in Honolulu on May 5 from Tokyo for a month’s visit in the islands before returning to the mainland after two months’ trip to Japan as guests of the Japan Travel Bureau. … Mrs. Tashiro, the former Kimiko Mukai, met her mother in Japan for the first time in 20 years.

After returning from Japan, Kimiko moved to Chicago to live with Tashiro, and their son Wayne was born in 1954. Raised in their home at 4429 S Ellis Avenue in Chicago, Wayne remembered clearly that there were always patients in the dental office.11 He also remembered that his father was baptized in the house and that Reverend Harry Komuro from Hawai‘i presided.12 Reverend Komuro was the superintendent of the Methodist Church’s Hawai‘i Mission.13 The event was celebratory as well as a great reunion, Wayne recalled.14

Wayne never heard either of his parents discuss Buddhism, and did not know at all that his father had practiced Buddhism. He thinks that his mother convinced his father that being baptized was a good idea, and that the baptism was something that they both thought would bring them closer together. He said that he didn’t think that “there was any feeling of negativity or resentment resulting from coercion. “15

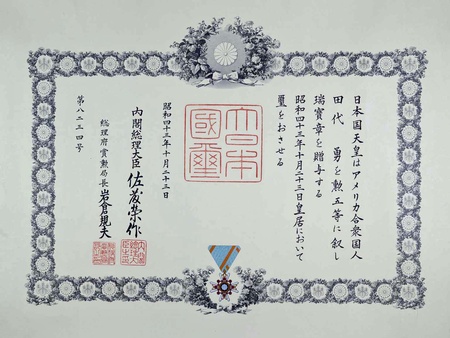

Order of the Sacred Treasure

Tashiro continued to practice as a dentist on Chicago’s South Side until he was well into his late 70s or early 80s— over a career that spanned more than six decades.16 Even after the war, he treasured his bond with Japan and endeavored to help in any way he could. For example, he “took with him between $3000 to $4000 worth of technical books and magazines and presented them to eight dental schools in Japan.”17

Wayne Tashiro said of his father, “He tried to build relationships between Japanese dental schools and dental organizations in the U.S. He led several trips to Japan, Hong Kong, and Hawaii for dentists in the Chicago area. The last one was during the Tokyo Olympics.”18

Tashiro’s devotion to building a better relationship between Japan and the U.S. for so many years earned him the Fifth Order of the Sacred Treasure award from the Japanese Emperor in 1968.19

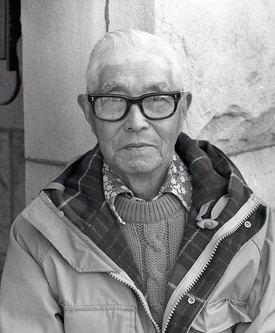

Later Years

Although he gave up playing baseball at some point, he was an avid golfer in the later years of his life, and one photograph features him holding a uniquely crafted bamboo-shafted putter, manufactured by his friend, Torikazu Toda.20

In May 1949, Tashiro created a golf league called Eagle Golf. Its members were Japanese-speaking Japanese Americans who had relocated from wartime incarceration camps. Tashiro was the first president of the club, which eventually became popular enough to sponsor about twenty-five tournaments each golf season, from April to October.21

He actively participated in games, even in his 70s, and “placed fourth with an 84 in the Jackson Park Golf tournament in 1972 at the age of 76.”22 The following year, he was one of the finalists in the senior citizen golf championship at the Waveland Course in Lincoln Park.23

Tashiro passed away on December 13, 1983 in Chicago at the age of 88.24 He left a legacy of improving the lives of Nisei from Hawai‘i and the Japanese Americans in Chicago and the West Coast. Tashiro’s FBI collaboration and conversion to Christianity may seem puzzling on the surface, but when one considers his decades of determined efforts to bring Japan and the U.S. together and fostering cultural exchanges, these activities might be explained as necessities of wartime, personal faith, and love.

Notes:

1. Asia and The Americas, March 1943.

2. Nippu Jiji, April 26, 1940; Shin Sekai Asahi, May 9, 1940; Nichibei Shimbun, May 3, 1940.

3. 1941 Nichibei Jyusho-roku.

4. Chicago Telephone Directory September 1942.

5. Chicago Telephone Directory January 1945.

6. 1948 Japanese American yearbook.

7. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 7, 2022.

8. Ibid.

9. Nippu Jiji, February 12, 1940.

10. Nippu Jiji, June 30 and August 25, 1941.

11. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 7, 2022.

12. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 9, 2022.

13. Hawaii Times, February 25, 1954.

14. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, August 11, 2023.

15. Ibid.

16. Chicago Tribune, December 21, 1983; Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 7, 2022.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Chicago Tribune, December 21, 1983.

20. Chicago Tribune, January 3, 1969.

21. Ryoichi Fujii, Shikago Nikkeijin-shi, pages 340-341.

22. Chicago Tribune, December 21, 1983.

23. News Journal, June 27, 1973.

24. Chicago Tribune, December 21, 1983.

*All photos courtesy of Wayne Tashiro.

© 2024 Takako Day