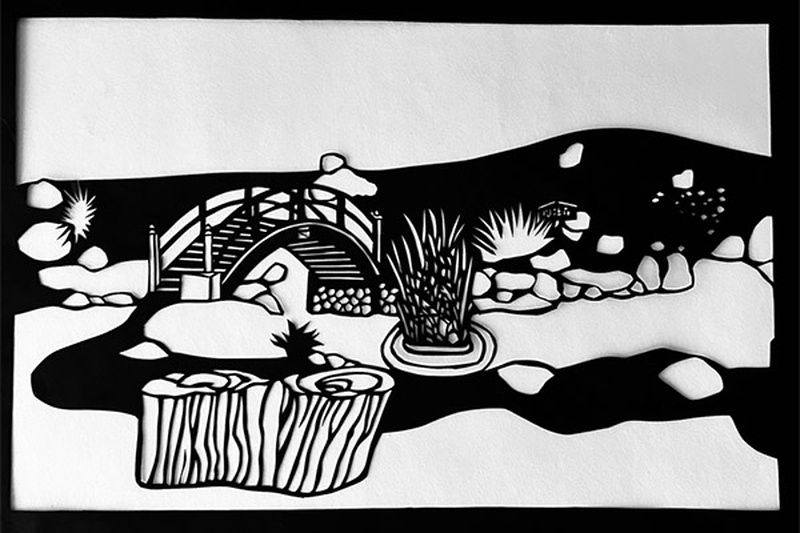

While the sakura were in full bloom outside the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, inside, a different kind of sakura blossomed, Japanese Australian artist Elysha Rei’s new installation called Strength in Sixty Sakura. Part of the JCCC’s new anniversary exhibit, 60 Years of Friendship Through Culture, the piece is constructed entirly of intricately cut paper, using kiri-e, a Japanese paper-cutting practice.

Two sakura branches reach out from opposite ends of the wall, adorned with 60 sakura, commemorating each year of education, partnership, and participation at the centre. The sakura represent the strength and resilience of the Japanese Canadian community, as captured in the history and programming of the JCCC.

“They’re just so vested in symbolism, even today, they’re almost part of the Canadian vernacular. They line the streets and are in so many different parts of the country, but there’s still that connection to Japan,” Rei tells Nikkei Voice n an interview.

“I thought they’re wrapped up with so much history and symbolism, and they would make really beautiful artwork.”

Rei is a Japanese Australian artist based in Brisbane who explores narratives of cultural identity and site-specific history through paper-cutting and public art. Currently completing her PhD at the Queensland University of Technology, her work has been exhibited across Australia, Japan, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Thailand, the U.S., and now Canada.

Rei was also drawn to the long history of cultural symbolism of sakura in Japan. Once a symbol of colonization, imperial Japan would plant sakura to transform foreign lands into Japanese territory. But following the Second World War, sakura became a symbol of peace and friendship between nations.

“In another sort of ironic twist, they became like olive branches or symbols of peace. Post Second World War and even in the ’30s, Japan gave sakura trees into certain cities in Canada as a gesture of peace and goodwill,” says Rei.

While the paper appears delicate, it’s heartier than it looks, just like the sakura. Made with a synthetic polymer paper, a plastic-like paper often used in advertising, it can be cut but not torn and is unaffected by water or humidity—made to endure the year-long anniversary exhibit.

Before visiting Toronto, Rei was in Victoria for an eight-week artist residency with the University of Victoria’s global project, Past Wrongs, Future Choices. During the residency, she researched Japanese Canadian, American, and Australian histories, also drawing upon her family history, to explore transcultural and ambivalent Nikkei identities in the postwar period.

During her time in Canada, she felt embraced by Japanese Canadian communities and felt an instant kinship with the Nikkei she met. Despite coming from different countries and backgrounds, in meeting and sharing stories, she found commonalities and shared experiences in their Nikkei identities.

“In between Japan and Canada and Australia, there’s this third space of Nikkei identity, and I think that’s where I’ve found that connection with people. We don’t quite fit in either of those other spaces, but in that third space, we can talk about the same things together,” says Rei.

“There’s a lot of parallels about the internment, the displacement, the dispossession, and so forth, but even about celebrating what we love about Japan. We don’t quite fit in when we’re over there either, but there’s still things about Japan that we can celebrate and ritualize in our everyday lives that maybe people without Japanese ancestry wouldn’t understand.”

Like many mixed-race Nikkei, Rei’s connection to her Japanese culture is deeply tied to her relationship with her grandmother. While her grandmother’s postwar experience in Australia differs from the Japanese Canadian experience, parallels run through.

Born and raised in Japan, Rei’s grandmother, Akiko, was working as a typist after the war when she met Glen, an Australian soldier stationed in Iwakuni, part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces. They fell in love, married in 1948, and their first daughter was born in Japan. After being stationed in Japan for eight or nine years, Glen wanted to return to Australia with his young family, but the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act prevented that, says Rei.

Also called the “White Australia policy,” the law aimed to limit non-white—and, particularly, Asian—immigration into Australia and wasn’t completely dismantled until 1973. In 1952, Australia granted Japanese wives, children, and fiancees of Australian servicemen entry into the country.

Similarly to Canada, Japanese immigrants began arriving and settling in Australia in the late 18th century. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Australia declared war on Japan, and within 24 hours, all Japanese Australians were rounded up and interned. The Australian Enemy Alien Registration Act was in place, and camps already existed for German and Italian prisoners of war. Following the war, almost all Australians of Japanese ancestry were deported to Japan, even if they were born in Australia. Only about 114 remained in the country.

In 1953, eight years after Japanese Australians were deported, Akiko was heading into a country with hostile attitudes towards the Japanese. She was among 650 war brides and their children immigrating to Australia, and by that point, she had not seen Glen for a couple of years.

Rei’s mother was born in 1954, the second of four children and the first baby born to a Japanese war bride in the Australian state of Queensland. Rei has photos of a local newspaper article featuring her grandmother and newborn mother on the cover.

“I think it was this big risk that she took because some war brides never managed to reunite with their Australian husbands—they may have already had a family back in Australia. She was really lucky to be reunited with him and was really embraced by his family, which also wasn’t the case for a lot of other war brides,” says Rei.

“I think she came to a country that was, for many people, not an easy one to come to if you were of Asian descent, let alone Japanese, because you were a former enemy of Australia.”

During the war, Japan had breached Australia’s home soil, bombing cities like Darwin and Townsville, and Australian prisoners of war from Japanese camps were returning home, sharing their horrific experiences. The anti-Japanese sentiment and racial discrimination against Japanese Australians “made it very difficult to be a Japanese person in the 50s and 60s in Australia,” says Rei.

The small Japanese Australian community assimilated to survive. Some changed or Anglicized their names. Rei’s grandmother only spoke English, even at home, to perfect her language skills. She cooked Western food and did not pass much Japanese culture and traditions to her children, says Rei.

“That was a real big loss of culture, and I think she tried to protect her children as much as she could by trying to assimilate them to the point where they wouldn’t be any different than they already looked… They just wanted to be Australian, and that was it. They weren’t Japanese Australian,” says Rei.

It wasn’t until Rei became a mother that she started thinking about her Japanese ancestry. She began asking her grandmother questions about her culture and past.

“That’s when you start to think about family history and ancestors, and I was really close to my grandmother, and she was passing these stories on to me, and it just sort of hits you, this is my culture as well,” says Rei.

Akiko taught Rei how to cook Japanese food, shared stories about their ancestors, and the two travelled to Japan together, visiting all the places from her grandmother’s past together. Akiko passed away last September at 95 years old. Rei recognizes that since her grandmother first immigrated and when her mother was growing up, there has been a shift in the public perception of Japanese culture.

“It’s probably very similar in Canada to Australia, where everybody loves Japanese culture, they love embracing all different parts of it, whether its karaoke, ikebana, or matcha lattes, it’s a very celebrated culture that people like to enjoy, but it’s taken only one generation to change that, and my mum’s generation would have never been anything like that at all,” says Rei.

During Rei’s time at the University of Victoria, she explored the tension between the generational experiences of her family as Nikkei in Australia. She explores the contrast in her identity as a third-generation Nikkei Australian, from her pride in her Japanese cultural heritage to the intergenerational remnants of pain from the racial discrimination her mother and grandmother experienced.

Researching oral histories and archival records for Canada, Australia, and the U.S., Rei created an art series called Kiri-e Nikkei: The interstices of diasporic displacement.

One piece recreates a photo from the Australian War Memorial of a charnel house built by Japanese Australian internees. Traditionally, a place to bury skeletal remains, Japanese Australians built the structure to commemorate fellow countrymen who passed away in the camp. With excruciating detail, Rei recreates details down to the fencing and stone work entirely out of cut paper.

In another piece, she creates a fuki plant, or Japanese butterbur, often used for Japanese home cooking. As Japanese Canadians were uprooted from their homes in coastal B.C., some took fuki seeds and planted them in internment sites as food and a reminder of home. Long after Japanese Canadians have left, fuki continue to grow there, like markers of what once happened. As Rei cuts away the paper, deciding which pieces to keep and which to let go, a narrative forms, visually and metaphorically.

“That positive and negative space and creating light and shadow is sort of a metaphor for illuminating certain things and bringing things out of the shadows. I like to hopefully put stories and histories in my work that need to be illuminated in some way and can enable people to learn something that maybe they didn’t know before,” says Rei.

By the time the JCCC’s 60th-anniversary exhibit opened, Rei had returned to Australia. One of the things she will miss the most about Canada is how she felt embraced by the Japanese Canadian communities in Victoria, Vancouver, and Toronto. The experience has strengthened her interest in learning about and connecting more global Nikkei communities and sharing Japanese Australian stories and histories.

“I feel like since I’ve come to Canada and have globalized my identity as a Nikkei person, I just want to meet more Nikkei people and embed myself in these communities,” says Rei. “I think our Nikkei community in Australia is so small comparatively, I’m going to miss being a part of the community in everyday life.”

* * * * *

To learn more about Elysha Rei, visit www.elysharei.com.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Voice on June 22, 2023.

© 2023 Kelly Fleck