I remember walking through my Grandma Kuida’s garden as a child. She had ten or twelve rows of different vegetables growing, and lots of old rusty cans and tools. Along with a bountiful lemon tree, her small backyard garden near Crenshaw and Jefferson was filled with delicious tomatoes, Japanese cucumbers, and zucchinis. When she hunched over with her apron full of fresh-picked vegetables to send home with us, she was 4½ feet tall. But to me, she was a gardening giant.

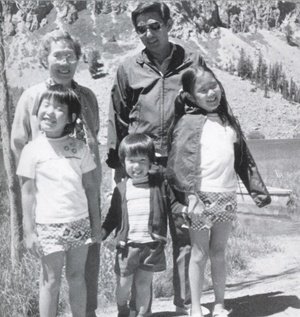

Before the War, my Issei grandma lived on a cantaloupe farm in Canoga Park, at the west end of San Fernando Valley. Of course, Grandma and Grandpa didn’t own the farm because of the Alien Land Law, but they rented it from an Italian family. My dad tells me how primitive it was—no running water or hot water. The only electricity was a single light bulb hanging in the kitchen. They had chickens and an outhouse, and I’m guessing they ate a lot of cantaloupe.

In the last dozen years or so, I’ve become a backyard gardener, too. It ties me to my Japanese American family roots, my community activities, and interests. When I’m gardening, I think about my grandma. I recall how in her late-80s, she broke her back digging in her garden, and kept on going. She was that much of a bad ass. But as she got older, her backyard garden got smaller and smaller.

One of the best things about growing your own food is the sense of accomplishment it brings. It’s hard work. Preparing the soil, digging out old roots, composting vegetable scraps; it all takes extra time and effort. It can also be a bit stressful—dealing with green tomato horn worms, birds, blossom rot, blight, you name it. But biting into a juicy homegrown organic tomato after watching it grow and develop, is an incredible taste sensation. Sharing zucchinis with friends and relatives like Grandma did makes me feel connected to her.

For me, gardening and farming are also political. It means less time in the grocery store spending my money on tasteless fruits and vegetables that have traveled from faraway countries I have never visited. Instead, I try to go to the Farmer’s Market to buy organic, pesticide-free, and locally grown foods as often as I can. I even participate in a food co-op at Little Tokyo Service Center where I work. A few of us go down to the produce market every two weeks at 7 a.m. to buy fruits and vegetables and then sell them at cost to people at the office.

My interest in gardening has taken me to Detroit, Michigan, a dozen times, where I have worked alongside young people from an organization called Detroit Summer. The youth in Detroit see community gardening as a way of beautifying the city. They take over empty lots, and turn them into vegetable gardens, all part of “rebuilding and re-spiriting” Detroit.

I have even been to Cuba with the first Japanese American delegation in 2001, where we met Miguel Harada, a Japanese Cuban Nisei whose family farm produces most of the watermelon on Isla de la Juventud. It was the juiciest watermelon I’ve ever tasted. We also visited another Japanese Cuban farm near Havana, where the lack of access to gasoline and fertilizers has allowed them to practice organic farming, and they even use rabbit poop as fertilizer.

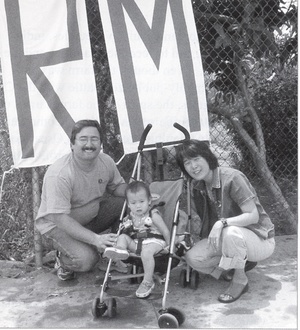

I also have been able to share my passion for gardening and activism with my daughter Maiya. Back in Summer 2006, when Maiya was just barely learning to walk, my husband Tony Osumi and I got involved with the South Central Farmers’ struggle, going to the 14-acre farm several times a week to join the candlelight vigils and marches around the farm.

In a community marked by warehouses and urban blight, the South Central Farm was lovingly tended by hundreds of people for fourteen years. Where immigrants came together to plant seeds, grow organic fruits, vegetables, indigenous herbs, and to feed their families and the community. Even though the farm was bulldozed in a highly-publicized battle with the City of Los Angeles, the spirit of the farm carries on today with their Farmer’s Markets, Community Supported Agriculture ventures, an Oscar-nominated documentary, and a new nonprofit cultural and community center located adjacent to the farm.

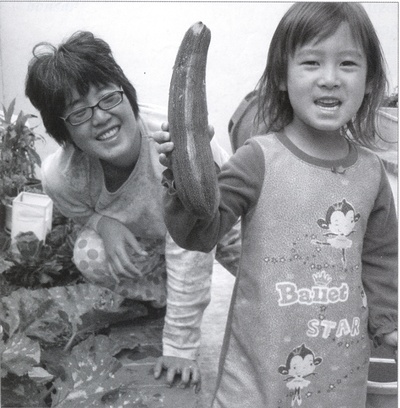

When Maiya was three years old, she and I planted her first garden together in small pots in the backyard. She helped dig, plant seedlings, watered the plants, picked and ate ripe strawberries directly from the backyard. In these moments, I am teaching her some of my grandma’s values of hard work, patience, and resilience. She is also learning to love the taste of fresh fruits and vegetables, learning about healthy foods, and learning that food doesn’t only come from the store, but from our own backyard.

Last year, we moved to a new house in Culver City, just a few miles from where my grandma grew her garden for over forty years, until her death in the early ’90s. Maiya and I eagerly planted tomatoes, cucumbers, yellow squash, zucchinis, strawberries, beets, peppers, and herbs. We even took a plate of tomatoes to our new neighbors. I couldn’t help but think of my grandma, and the legacy of gardening that she passed on to me, that I am passing on down to my daughter.

* This article was originally published in the Nanka Nikkei Voices: The Japanese American Family (Volume IV) in 2010. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2010 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California