“I won’t sell. You can murder me, you can throw me into the sea, and I won’t sell.”

Mr. Jukichi Harada’s sharp yet courageous response was unlikely to be the type of exchange he envisioned carrying on with his American neighbors when he left Japan permanently in 1903, never to see his parents, brother, or sisters again. For Issei, such as Mr. Harada, who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship, owning a building or land became that much more significant in representing a long-term, if not permanent, stake in this country. Unfortunately, having the state of California try to remove his family from their home was his heartbreaking reality.

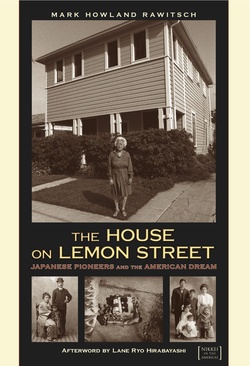

Mark H. Rawitsch, who authored The House on Lemon Street and is Dean of Instruction at Mendocino College, grew up in nearby Whittier. He went to school with a few Nikkei friends and his family dentist was Japanese. In his early twenties, Mark lived for a time in Hawaii and “worked as a security guard at the front door of the Waikiki duty-free store where most other employees were Japanese immigrants or Japanese American Hawaiians.”

He returned from Hawaii to study anthropology and archaeology in college. While participating in several archaeological excavations in the early 1970s, Mark soon realized that it was “next to impossible to determine with certainty what kinds of events actually occurred on a daily basis, or what sorts of emotions were expressed at a long-vacant habitation site.”

Enter the Harada family

When Mark first visited Jukichi’s daughter, Sumi, at the Harada House on Lemon Street in 1976, “[he] was struck that a 1942 calendar was still there hanging on the wall, and that nothing much had changed inside Sumi’s house since before World War II.

Some of the personal effects and even the clothing of Sumi’s father Jukichi and mother Ken Harada were still in the closets, even though Mr. and Mrs. Harada had both died 30 years before at Topaz—it was as if [Mark] had entered an aboveground archaeological site that was still inhabited by someone who could tell [him] her family’s story in detail.”

Mark would later describe that initial visit as entering a time warp in the Twilight Zone or discovering the untouched King Tut’s tomb of Japanese American history.

We are grateful to Mark for seeing his book through to the end because compared to the volumes written about Japanese American life during and post-WWII, relatively little is known about day-to-day lives of first- and second-generation families prior to WWII. The preservation of the Harada House, as well as the writing of this book, considerably improves that landscape.

Mark was fully aware of this gap when writing his book.

When he first developed the story of Mr. Harada’s court case, “which involved telling the story of the Nikkei community in the early 1900s and the challenges they faced with citizenship and the desire for home ownership, [Mark] introduced that story by saying that most Americans think that Japanese American history began ‘somewhere behind the barbed wire fences of America’s concentration camps.’”

In other words, Mark meant “that many of us do not do very well in understanding the longstanding forces that gradually lead us to the more dramatic moments in history.” As readers have commented to Mark, many Americans have “no idea how many years before Pearl Harbor the Japanese in the U.S. were struggling for acceptance and confronting numerous legal challenges to their very existence.

Readers have said that they now have a much better understanding of the forced removal because of what they have learned about that earlier Nikkei story. Mark believes such a well-rounded understanding—of not only the Japanese American incarceration, but also of other more recent tragic events in our country—can only help people “more fully realize how the apparent ‘surprises’ in history really are often not surprises at all.”

Mark takes great pride in publishing a book that paints this fuller picture of Japanese American history. As Mark puts it, “Each time a reader tells me that they appreciated having a version of the entire Japanese American story in one book (pre-war, wartime, post-war), it makes me proud to have been able to tell the story in a way that seems to resonate for people.”

Even though this fuller picture unfolds with the Harada family’s experiences, The House on Lemon Street stands out from other published memoirs in that Mark does not merely incorporate the historical context as an afterthought or gloss over it with broad strokes; he practically gives it a life of its own.

By so doing, Mark ensured that this book would not be limited to a story of how one particular family coped with Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066, and camp life. Rather, by committing over half of the book’s pages to a detailed narrative of the several decades leading up to WWII in both American and the Harada family’s histories, Mark has performed a far greater service for our collective understanding of the forces that gradually led America to the appalling, singular moment of Japanese American incarceration.

We have been fortunate to have so many people publish their painful memories of those dark days of incarceration, but we have not always had the same occasions to revisit Japanese lives prior to WWII, much less prior to WWI.

Dr. Harold Shigetaka Harada and Mark Rawitsch, 2000: Photo by Dana Neitzel, Riverside Metropolitan Museum Collection

Throughout its pages, especially Chapter 3, the book provides a great historical overview of the tense sociopolitical climate of pre-war America and its Asian immigrants. Also, Chapter 4 thoroughly discusses Riverside, home of the Harada House, around the turn of the twentieth century that most of us will find as a new and enjoyable read. Sufficient for this article, however, is that Mr. Harada arrived in California during a period consumed by “50 years of anti-Chinese agitation and greeted by a robust heritage of anti-Asian legislation in most western states” and when Issei “were met with hostility and the belief that people of color did not qualify for equal treatment under U.S. law.”

Additionally, the anti-Japanese movement gained steam early in 1905 with a series of San Francisco Chronicle articles criticizing the Japanese and prompting the California legislature’s unanimous passage of an anti-Japanese resolution.

Moreover, despite the perception that President Theodore Roosevelt and international politics complicated such ignorant hostility in California, the Alien Land Law of 1913 was passed.

The law, which denied real estate ownership to aliens ineligible for citizenship, would later be described in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision of Oyama v. CA as “the first official act of discrimination aimed at the Japanese.”

Supposedly the rationale behind the law centered around the competition for agricultural land; however, it is significant and rather revealing that the first challenge brought under the Alien Land Law (case against Mr. Harada) stemmed from “the worry and agitation over the purchase of residential property by a Japanese American family trying to live among white neighbors” in a place some insisted had been and should always be, as US Senator James. D. Phelan had said, “White Man’s Country.”

People v. Harada garnered nationwide coverage, including the New York Times and the Washington Post. Mr. Harada believed the best chance to provide a safe and permanent home for his children was to rest the interest of the house in his three youngest, American-born children, so he arranged to record ownership of the property in their names.

Ultimately, the case was ruled in favor of Mr. Harada and the Harada family continued living on Lemon Street. The judge in the case explained that Issei’s children born on American soil were entitled to the same constitutional guarantees and privileges as that of every other US citizen. Furthermore, the judge stated that the deed did not include Mr. Harada, so he could never claim a legal interest in the property, even if there were no Alien Land Law.

Unfortunately, unbeknownst to the Harada family, the WWII removal and incarceration were still ahead.

In The House on Lemon Street, one message that rang through loud and clear was that “ordinary people can respond to challenges with extraordinary courage.” Immigrants with limited resources, such as Mr. Harada, who stuck to their principles and dedicated their lives to make a better life for their families, should all be commended for their extraordinary courage. As to Mr. Harada specifically, it no doubt took extraordinary courage to stand up to his neighbors so that his family might remain in their home.

For the younger generations today, the role models in The House on Lemon Street do not end with the Japanese immigrants and the Japanese Americans. One can only imagine the extraordinary courage necessary for Caucasians to support or befriend the Japanese and Japanese Americans at the time.

Strong examples of courageous Caucasians that readers can find in the book are Frank Miller of the Mission Inn, the attorneys that defended Mr. Harada, the judge that found in Mr. Harada’s favor, and Jess Stebler who cared for the Haradas’ home during incarceration. Mark depicted these community members assisting the Harada family in his book to show that, “in future times of conflict, other ordinary people can and should come forward to help those in distress.”

Individuals in his book are not the only people for which Mark is grateful. He also has been “moved and humbled by the willingness of [Harada] family members to share their stories.” He will cherish being able “to work with, or obtain information from, four generations of the family.”

He is also appreciative for those who have thanked him “and, by extension, the Harada family, for [their] efforts to tell stories that have resonated with other Nikkei families within which little or nothing was said of the experiences of WWII.” Sadly, some of Mark’s own friends never knew their relatives had been sent to the camps until after they had passed away.

So the takeaway? According to Mark: “Talk to your elders!” To be clear, Mark’s message is not intended for only Japanese Americans. While some may think that the unique circumstances faced by the Nikkei community make its members very different from other Americans, Mark contends “that all American families have meaningful stories to tell.

Without knowing about your own family’s past, and making an effort to understand the struggles experienced by most of our immigrant ancestors, regardless of their ethnicity, [Mark] “believe[s] Americans in general cannot comprehend the promise and possibilities of the American Dream.”

In the end, this book may be more about America itself than about either the Harada family or the pre-war Japanese experience. Mark really wants readers to understand “that the forced removal of WWII did not simply spring from the few minutes after Pearl Harbor—that there was a much wider arc of earlier discriminatory events that, over many years, eventually culminated in that event.”

While Mark understands the Nikkei focus on the wartime removal, he also believes “it is critical for everyone to understand that it is oftentimes possible to see things coming well ahead of time and, if people would pay more attention to some of the current themes and responses to things like immigration policy, for example, they might work harder to adjust our society to accommodate change more smoothly. As a result, we might be able to avert future mistakes that take decades to resolve.”

Mark believes that “all Americans need to understand that each wave of immigrants has brought great energy, renewal, and promise to the future of the U.S., and that each group has struggled with acceptance.” For example, “the African American experience, which grew from an earlier forced removal from native lands, has parallels with the Nikkei experience of the loss of home in the 1940s.” Also, the Irish American experience in the nineteenth century, which grew from conflict over labor, workplace rights, and social acceptance, has parallels with the present-day Latino American experience.

“Through a more comprehensive understanding of this commonality of experience, centered around the wish to make a better life for one’s family and descendants—described by some as the American Dream—[Mark] think[s] all of us today should be able to do a much better job of understanding and assisting immigrants with their own quest to realize their own version of the dream.”

Today, Mark is extremely proud that, while based on his and Sumi Harada’s initial efforts to nominate the Harada House as a local historical landmark in Riverside, others elsewhere saw fit to nominate and follow through with the designation of the house as a National Historic Landmark. Sure, the Harada House will be historically significant because of its association with the first Japanese American court test of the California Alien Land Law of 1913 and for its later link to the experiences of the forced removal and return. Perhaps, more importantly, however, it will leave a broader, more encompassing legacy.

It “will tell its proud American story for many years to come—a place for teaching, learning, and personal reflection about the struggle for the American Dream; a reflection of the opportunities and responsibilities of freedom, family, and citizenship; and a story of our successes and failures as different Americans seek to find their place in the world.” In this light, as only Mark would have it, the Harada House will undoubtedly become known to be truly more than just a house.

Mark was honored that his book was chosen as the first work in the George and Sakaye Aratani Nikkei in the Americas Series, developed by Dr. Lane Hirabayashi, Professor of the Japanese American Incarceration, Redress, and Community at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University Press of Colorado. He was also honored with recognition for his book outside the Nikkei community with the inaugural Crader Family Book Prize in American Values.

Please join us on August 3, 2013, at 2 p.m., as the Japanese American National Museum hosts author Mark H. Rawitsch for a book discussion regarding his work, The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream.

(For more info >>)

If you are unable to make this book event, it is available for purchase in the Museum Store or online at http://janmstore.com.

Upcoming projects

Mark is interested in working again with the Riverside Metropolitan Museum and maybe JANM “to develop a catalog of the Harada family collections, promote new exhibits and, perhaps, a documentary or motion picture about the story of The House on Lemon Street.” He would be grateful for any referral suggestions to get the ball rolling on some of these potential projects.

© 2013 Edward Yoshida