I will begin with a story. Over a century ago, Japanese immigrants landed on North America’s shores brought by the warm waters of the “Kuroshio,” or Black Current, which travels a perpetual circle from Japan south to the Pacific Islands and then up along North America’s west coast and back again. Transplanted adventurous peasants from a feudal island, we helped to clear the forests, to harvest the seas, and to develop a virgin country.

In those days, Japanese fishermen attached clear glass balls the shape of grapefruits or small watermelons to their fishing nets to keep them afloat. Thousands of these balls freed themselves and have been drifting on the waves of the Black Current, eventually to be washed up on Canada’s shores. Buffeted by the sea and the winds, the glass balls are by now, a beautiful opaque bluish green colour. For some, they are simply the flotsam and jetsam tossed onto the beach, for others they are exotic objects of interest, collector’s items.

Carried here by the warm waters of the Black Current, we Japanese Canadians were also pummeled by the sea and the winds, and over the years our skins have been sandpapered by the hostilities we have endured. We also have been rubbed raw and rubbed smooth.

Let me tell you of my community’s experience in Canada. It is a tale initially of relentless discrimination to final acceptance by the white majority through virtual assimilation. I will start at the beginning. Japanese migrated to Canada from the late 1870s to the 1920s.

Fishing boats along the Fraser River at Steveston, BC. (British Columbia Archives; Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre Archives. Photo courtesy of JCCC)

The first Canadian census of Japanese immigrants in 1901 indicated some 4,738 (primarily single males). From 1905-1907 a further influx of 12,000 was recorded.1 This sudden mass arrival of Asians (i.e. Chinese and Japanese) culminated in 1907 with race riots, when gangs of whites vandalized and terrorized Vancouver’s China and Japan towns. The “yellow peril” problem was addressed through the 1908 Hayashi-Lemieux “Gentlemen’s Agreement” that restricted immigration from Japan.2 With limited immigration and with an 80% return migration to Japan, by the outbreak of World War II, the Japanese Canadian community numbered some 23,000 living primarily along the coast of British Columbia.

Upon landing in Canada, Japanese Canadians have been subject to virulent racism.3 At one time, we were visible, shunned, and discriminated against…the most hated minority in the country. Yet our history of racism did not begin at the outbreak of WWII but stretched back to our arrival on North America’s shores.

Noteworthy are the following facts: in 1895, the British Columbia provincial “Elections Act” which had deprived the Chinese and East Indians of the right to vote was amended to include Japanese immigrants and their children born in Canada.4 As a result Japanese Canadians were denied most of the rights whites took for granted. Since being on the provincial voters’ list was a frequent job requirement, many employment doors were slammed shut. (Effectively Japanese Canadians could not obtain timber leases, log on Crown lands, receive government contracts, or work as public school teachers, underground miners, and provincial or municipal civil servants. They were also denied entry into professions, such as law and pharmacy.) Japanese Canadians were refused basic civil liberties as the right to vote, serve on juries, and to run for political office. The prohibition of the franchise and citizenship rights remained in place until 1948 for Canadian Chinese and East Indians and 1949 for Japanese Canadians. Many felt trapped in Canada.

We could not forget,

Nor yet go back to Japan.

Without our homeland

Most of us Issei were like

Trees that were slowly dying.—Kimiko Ono, an Issei immigrant

Anti-Asian Riots, September 8-9, 1907, Vancouver, B.C. (Public Archives Canada, Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre Archives. Photo courtesy of JCCC)

The War Years

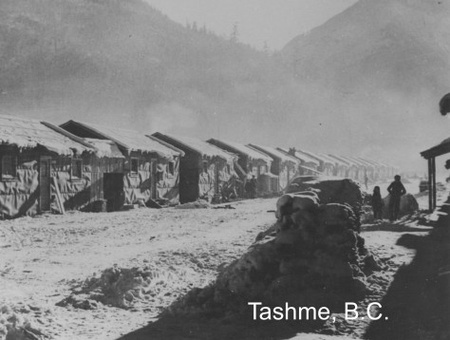

In early 1942, after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, my family like all Japanese Canadians was deemed a security risk and uprooted and relocated into a prison camp deep in the British Columbia interior. Families were broken up. Men sent to work gangs; women and children to internment camps.

This was done despite advice from the Canadian military to Prime Minister McKenzie King’s government that Japanese Canadians did not pose a defence threat. In 1943, the Canadian government seized and sold the internees’ property and used the proceeds to pay for the cost of their imprisonment.

After the war in 1946, the Canadian government attempted to deport and exile Japanese Canadians to war-decimated Japan. By 1947, some 20% (4,319) had left on American troop carriers for Japan, a country most did not know. The remainder still held in camps were dispersed across Canada and prohibited from returning to the West Coast of B.C. until 1949. My family, like 80% (18,000+) of Japanese Canadians decided to resettle in eastern Canada, where it was whispered, there was less racism. In 1948, when my family was released from the internment camps, they relocated to Hamilton, Ontario, where I was born, partly because my mother, who had been born near the snow-capped Rockie mountains in northern British Columbia, had heard there was a “mountain” there.

In leaving B.C.,

We left family and friends.

Many were reunited but it was not the same.

Nor will it ever be the same.

And in going forward we tried

with many a backward glance to keep in sight

all that we held dear to our hearts.

The time comes when we must lose

the last link to these too,

and until the moment when one takes

the last step into oblivion,

one remembers the sound of fading footsteps,

the quiet sadness of a silent farewell.—Muriel Kitagawa, 1946

Winter at Tashme internment camp, B.C. The houses were not insulated. (Public Archives of Canada, Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre Archives. Photo courtesy of JCCC)

The Hamilton (Canada’s Pittsburgh) of the 1950s and ‘60s that I remember was white, a multi-cultural mix of immigrants who were escaping poverty and wartime displacement in Europe. I didn’t need my reflection in the mirror to tell me that I was different, that alien blood flowed through my veins. One evening when I was a young child, my father came to walk me home from a Brownie meeting. As I excitedly described the secret knots I had just learned, a group of boys yelled at us: “Chink, Chink.” I immediately dropped his hand and if I could have I would have crossed the street. We walked home in silence. Early on we were taught to denigrate our parents and ourselves. I still carry with me, my childhood feelings of fear and self-hatred. Scar tissue has formed to cover those scrapes and I cannot say that they were unhappy days.

At just over 77,000, my community is one of Canada’s smallest minority groups. Strung out in tiny numbers, across the country along the tracks of the national railway, today there is no “Japantown”, no geographical heart where the community’s pulse can still be felt. Today, we are per capita among the country’s most highly paid, educated, and assimilated, in short an ethnic “success story”.6 With virtually no immigration from Japan, an intermarriage rate of about 96% and a fifth generation being born of only ¼ Japanese ancestry, our fate is sealed. Like dinosaurs, we are facing extinction. In the words of an old Japanese saying: “When the river enters the sea, the muddy river water mixes with the sea and is gone forever.”

After the war, my shattered community strove to become one hundred per cent Canadian, all the while fearful of the ever-present nightmare of a resurgence of racism. Canadian-born Japanese of my parents’ generation were prepared to pay the outward price of Canadian citizenship: total submersion. Offspring of proud Meiji pioneers, they spoke Japanese and uncomfortably had their feet planted in both cultures. My generation was consciously raised to no longer share the language, religion, and culture of our grandparents. My father fluently spoke, read, and wrote Japanese yet he talked to me only in English. While he attended Buddhist temple in Hamilton, I was sent to a Christian Sunday school. Cut off from my roots, nonetheless my reflection in the mirror spoke the truth that an alien blood flowed in my veins.

Although in 1947-48 there had been a very brief discussion by Japanese Canadian community leaders “about the possibility of redress,” the idea was quickly abandoned as “being so remote as not to be worth fighting for.”7 Still, our wartime history was a wound that festered within my community for almost four decades.

Perhaps we want nothing better

than to forget the raw wounds of yesterday;

to cover the scar with delusions of security,

but what was once taken away

can be taken away again.

Who knows but that the next time

will be made easier for the plunderers

because we shrugged and said “Shikataganai”

(it can’t helped)—Muriel Kitagawa, 1946

The idea of redress was to resurface thirty years later, occasioned in 1977 by our celebration of our first hundred years in Canada.

Notes:

1. Dermot Vibert, “Asian Migration to Canada in Historical Context”, (The Canadian Geographer 32, no. 4, 1988), p.352

2. Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was: A History of Japanese Canadians, (Toronto, McClelland and Stewart) 1979, chap. 3 See Adachi for a detailed history of Japanese Canadians pre-redress. 2nd ed. 1991.

3. Bruce Ryder, “Racism & the Constitution: The Constitutional Fate of British Columbia Anti-Asian Immigration Legislation, 1884-1909” (1991) 29 Osgoode Hall Journal 619. Ryder documents over 100 provincial statutes enacted between 1872 and 1922 discriminating against Chinese and Japanese.

4. Adachi, p.41

5. Ann Gomer Sunahara, The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War, (Toronto: Lorimer, 1981), pp. 118-128. Sunahara maintains that the repatriates did so under duress, amidst great confusion and misinformation.

6. Audrey Kobayashi, “A Demographic Profile of Japanese Canadians and Social Implications for the Future”, a Report for the Department of Secretary of State, Canada, Sept. 1989.

7. Tom Shoyama, “Redress and the War Time Years,” (Toronto: The New Canadian Newspaper, Vol. 49, No. 4 [January 18, 1985]), pp. 1-2.

The paper “Lessons from the JC Experience” was given on May 21, 2002 at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire. The Honourable Madam Justice Maryka Omatsu was the William Timbers lecturer, a guest of the Nelson Rockefeller Center & the Dartmouth Lawyers Association.

* * *

* Maryka Omatsu will be speaking at "Border Crossings: A Comparative Assessment of Japanese American and Japanese Canadian Redress" session at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity on July 4-7, 2013 in Seattle, Washington. For more information about the conference, including how to register, visit janm.org/conference2013.

© 2002 Maryka Omatsu