Read part 1 >>

Having now provided a snapshot of the pre-World War II Japanese American community in Orange County during the so-called “Issei Pioneer Era,” we need to shift our attention to the main focus of my presentation tonight, which I have titled “Nikkei Agriculture in Orange County, California, the Masuda Farm Family, and the American Way of Redressing Racism.”

Based on two oral history interviews done in 2006 with Masao “Mas” Masuda by, respectively, Susan Shoho Uyemura, for the Japanese American Living Legacy organization, and Takamichi Go, for the Center for Oral and Public History and the Garden Grove Historical Society, we are able to construct a portrait of the pre-World War II Masuda family in Orange County and trace the diverse experiences of that family through World War II and into the postwar period commonly known as Japanese American resettlement.

The Masuda family’s Issei parents, Gensuke and Tamaye, were both born and raised in Wakayama, one of the seven prefectures in southwestern Japan that supplied most of the emigrants to the United States. When Gensuke, while still a boy, immigrated into the United States in 1898, he worked on the railroads in Oregon, along with many other Issei.

Some years later, Tamaye sailed to Vancouver, British Columbia, in Canada, and it was there that she and Gensuke were married. Gradually, the couple worked their way southward along the West Coast until, as I noted earlier, they settled in Orange County around 1906 or 1907.

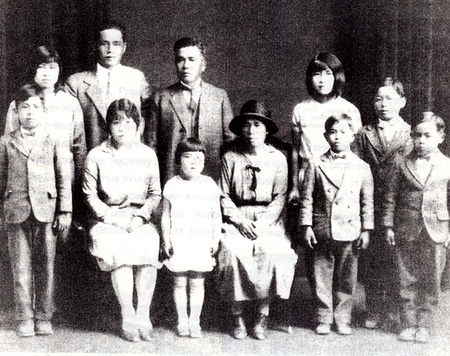

By 1908, the Masudas were blessed with the birth of the first of their ten children, eight of whom (four boys and four girls) would survive into adulthood. These Nisei offspring of the Masudas appeared on the scene in rapid succession: Takeo in 1908, Mary Fumi in 1909, Shiz in 1911, Hisako and Nobuo in 1913, Mitsuo in 1916, Masao in 1917, Kazuo in 1918, Takashi in 1920, and Masako June in 1922.

Early Photo of Masuda Family (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

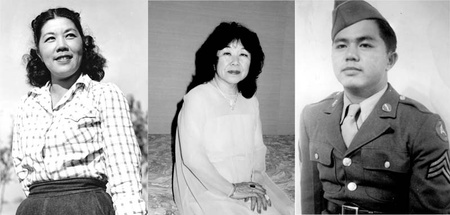

Although all eight of the Masuda progeny who reached maturity were loved by their parents and their other siblings and contributed to the family’s agricultural economy and well-being, three of them, as we shall soon see, would (because of their heroic deeds) assume a place of prominence on the historical stage of both Orange County and the United States. They were: Mary, the oldest daughter; June, the youngest daughter; and their brother Kazuo, or Kaz, the eighth child in the family.

From right to left: Mary, June, and Kazuo Masuda (Photo courtesy of Masao Masuda and Susan Shoho Uyehara, Japanese American Living Legacy/Nikkei Writers Guild)

At the time of Masao’s birth, in 1917, the same year the United States entered World War I, the Masuda family was farming 100 acres of sugar beets in the Orange County community of Westminster. Thereafter, the family moved to Tustin and grew mainly tomatoes. When Mas was in grammar school, around 1927-1928, the Masudas moved again, this time to Fountain Valley, then known as Talbert. There they grew strawberries, string beans, celery, cabbage—a lot of what is called “truck farming.” All of the Masuda kids, girls as well as boys, worked on the family farm. However, most of the girls married fairly young, since in those days they were among the oldest of the county’s Nisei generation, and consequently married the younger Issei who had migrated to Orange County and were seeking wives.

During the school year, the Masuda children went on weekdays to public grammar schools, including ones in Tustin, Fountain Valley, and Westminster, whose students were mostly Caucasian but included some Japanese Americans. The Westminster grammar school was destroyed by the devastating earthquake of 1933, which had its epicenter in Long Beach but caused a great deal of damage in Orange County. On Saturdays, the Masuda kids joined other Nisei in attending a nearby Japanese language school, or Gakuen.

Most of the Masuda brood matriculated at and became graduates of Huntington Beach High School, where the boys developed reputations as good athletes. Mas, for example, played football, basketball, and track, in which his specialty event was the shot-put. As for his younger brother Kaz, he was active in football, boxing, swimming, track, and cross-country running. After high school, the Masuda boys lived and worked with their parents and siblings growing mostly chili peppers on the Masuda farm, a 200-acre property located on Newhope Road in Fountain Valley.

On Sundays the Masudas would periodically attend religious services with other Nikkei pioneer families, who lived scattered apart at roughly quarter-mile intervals, at the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission. This structure had been built in 1910 upon an acre of land owned by Charles Furuta on Warner Avenue in Huntington Beach.

Then, in 1934, it was supplanted on the very same property by a new building that carried the name reflective of the enhanced status the congregation had gained four years earlier: the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church. It should be stated that most of the Nikkei families in Orange County could not attend the Wintersburg church or other community churches on a regular basis. This is because they were mostly farm families, which meant that family members usually had to harvest crops on Sundays so they could take them to the market on Monday mornings.

* This was a presentation at a public program in support of New Birth of Freedom: Civil War to Civil Rights in Californiaat the Orange County Agricultural and Nikkei Heritage Museum, Fullerton Arboretum, California State University, Fullerton on October 19, 2011

© 2011 Arthur A. Hansen