“When I was seventy-four years old, I was invited to participate in a writing class and began writing about those war years. The damn broke loose when those emotions and tears I repressed for decades broke through, at times seemingly uncontrollable. At last, I was telling my story – a Nisei no longer willing to be silent.” Author Mary Matsuda Gruenewald (1925- ), Looking Like The Enemy (2005)

I hope that you’ll forgive me for venting a little, but it seems to me that interest in the Japanese Canadian immigrant story has been rapidly diminishing since the Redress settlement in 1988, and our community has not yet woken to the reality that this legacy is quickly slipping away.

As I write here, I imagine doing so to a young Nikkei who might be groping in the dark for some sense of cultural identity, which was definitely the personal crossroads that I was at 20 years ago. Where does one turn to hear the stories of where we come from?

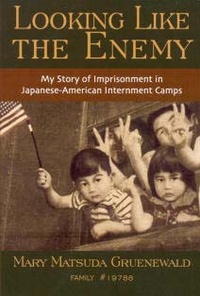

One’s family is a good start: pester anybody who might remember any of the old stories. It’s your birthright. There are also the books. My own literary journey has included the works of Ken Adachi (The Enemy That Never Was), Takeo Doi, MD (The Anatomy of Self and the Anatomy of Independence), scholar Ronald Takagi, Filipino writer Carlos Bulosan, cultural anthropologist Ruth Benedict, novelist Joy Kogawa (Obasan and Naomi’s Road), Shizuye Takashima’s A Child in Prison Camp, the short stories of Toshio Mori, John Okada’s seminal novel, No-No Boy, retired academic and poet Roy Miki’s book Redress, and most recently, Looking Like The Enemy by Mary Matsuda Gruenewald.

When I pulled Looking Like The Enemy off of the bookshelf at my parents’ place, I didn’t know what to expect. I’ve read a ‘few’ books about the internment experience as I am always looking for new ways to ‘see’ the Nisei experience, which begins with a complex mash of cultures, politics and economic circumstances that were beyond the control of any non-white community at the time. Look more closely at the complexities of the pre-World War Two Nikkei community (there were ‘rival’ groups), the country and even the province or state in which they were located, considering that every family circumstance was unique, too. Then you begin to get some idea about the impossibility of saying that any experience was definitive in any way.

Mary Matsuda Gruenewald’s courageous memoir of her family’s experience in American internment camps, after being exiled from Washington State’s Vashon Island, was so compelling for the plain honesty with which it was told (I could imagine my aunts of the same age telling it) and the familiar immigrant beginning and internment experiences, that were very much like our own Canadians one.

Heisuke and Mitsuno Matsuda brought Mary then 2 and brother Yoneichi, 4, to Vashon Island in 1927, where they first leased a small farm. By 1936, there were 37 Japanese families living on the island. Their story is one of the Issei’s remarkable work ethic and honesty, their “gaman” (perseverance) and “shikataganai” (a fatalistic feeling of ‘it cannot be helped’) that were the Japanese cultural values that sustained them through the toughest of times.

Like a many pre-World War Two rural Nikkei families, the Matsudas were hard working strawberry farmers. They were finally able to purchase their own farm on Vashon Island shortly before they were interned. When the foreign power of Japan attacked the United States in 1941, the Nikkei community was minding its own business, working hard to realize the American Dream even though there were so many obstacles before them. Like I said, the Nikkei community was not doing anything illegal. They were in fact model citizens by most accounts. So, even though the US and Canada were at war with other countries, too, the Nikkei who were living on the west coast of both countries were a target for the racially, economically and politically motivated politicians and the general public didn’t know any better than to believe all of the “Jap” propaganda that they were reading and hearing in the media.

Remembering that the Nikkei on Hawaii, which was a lot closer to Japan, weren’t interned, the west coast lives of 120,000 (US) and 22,000 (Canada) innocent Nikkei were irrevocably torn apart by this ‘perfect storm’ of hysteria, where racist attitudes were the norm. Remember: we were still decades away from the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. Blacks in the United States and Canada were openly discriminated against and the Ku Klux Klan’s reign of race-driven terror ran unabated.

Mary Matsuda was just 17 and a high school student when her family was sent to an internment camp along with all people of Japanese descent living in western Washington, Oregon and California. The family had a couple of weeks to pack their belongings and make sure that their Filipino lead hand understood what he needed to do while the family was being incarcerated. I expect that the average Nisei teen didn’t expect their own incarceration to be very long either. When the government began confiscating personal property, including homes, fishing boats, farms and businesses, it was with the expectation that they would soon be able to return to their coastal communities after the hysteria had settled down.

First there was the ‘Evacuation Order” for “all persons of Japanese ancestry” to vacate Vashon Island by May 16, 1942: “How long will we be gone?” “Why are they making us go?” Even, “Are we going to be treated like prisoners of war and executed?” These are questions that I could hear teenagers today asking if they were in the same situation.

The Matsudas were first sent to Pinedale Assembly Center, located close to Fresno, California.

Mary recalls: “As we entered the camp I stared at the barbed wire. Why is the barbed wire facing inward? I thought. Isn’t the government putting us here for our protection?”

“I often wondered, How can they (the Issei) be so endlessly stoic? On reflection much later, I realized that was the way they had always looked at life – with thoughtful planning, patience, faith and hope.” (p.57)

Next stop for the Matsudas was Tule Lake Internment Camp that had a peak population of 18,789, followed by Heart Mountain, and finally, Minidoka Internment Camp, Idaho.

Mary’s observations of the generational differences between the Nisei and Issei were striking:

“For the Isseis, group solidarity and maintaining meaningful parts of the Japanese culture had been essential for their survival. Most of the products and services used by the Issei, such as Japanese food, clothing entertainment, language school… had been an established part of Japantown for many years. They did not exist in the same way here in camp. Exposed to the norms of the white community back home, I began to feel disconnected in this environment… For example, boys and girls were pairing off, something we never did back in our pre-war lives. Mealtimes were no longer for the family to be together. I felt squeezed between two cultures. I had no guide to help me.” (p.88)

One of the most significant differences between the American and Canadian internment experiences was that the interned Americans were asked to sign a questionnaire that included these two loaded questions:

27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?

All Issei of both sexes and all female Nisei over 17 had to answer a different question 27:

If the opportunity presents itself and you are found qualified, would you be willing to volunteer for the Army Nurse Corps or WAAC?

Despite the threat of a $10,000 fine and up to 20 years imprisonment under the Espionage Act, those answering no to both questions, the “No-No” people stood their ground. (Read Okada’s compelling novel No-No Boy about the subject.) Mary, with some soul struggling decided to vote “Yes-Yes” as did the rest of her family including Yoneichi who enlisted in the army. Mary went to nursing school in Iowa, finished her training in 1947 and retired in 1990. After being discharged, Yoneichi became a Seattle high school teacher, passing away three months after retiring in 1985.

When I first started writing about the Canadian Nikkei community almost 20 years ago, it was with some alarm, even then, that we were doing such a poor job of documenting the stories of internment, racism, heroic battles to become the first doctors or police officers or teachers or lawyers of Japanese descent and our other remarkable Canadian stories. Today, the need to create opportunities to tell these stories in forums that will foster the telling of them is urgent. All of these stories then need to be put into some kind of permanent and easily accessible database that all Canadian can access.

In addition, especially in the absence of university programs that focus on Asian studies, there is a need to encourage more aspiring scholars and writers to step forward. We need to listen more carefully to our Canadian elders like Nisei Harold Yutaka Yoneyama (An Evacuee’s Memoir), 86, and provide whatever assistance they need to record their personal stories on DVD or tape while they still can. As a community we have to wake up to the reality that the Nisei are well into their twilight years.

We owe it to the Nisei to do a much better job of honoring their legacy than we managed to do for the Issei. We at least owe them that much.

I have been half-seriously wondering these days if we, as a community, have in fact integrated so well into mainstream Canada that we no longer need to remember the stories of how we got here. Is there any point to preserve the remarkable pioneer stories of the Issei? Was the internment experience really that ‘big a deal’ or, rather, an action that was truly necessary under the circumstances? As nobody has called me a “Jap” or “Nip”, at least not openly in recent years, why don’t we just shut up and be the good Canadians we are? Hasn’t society evolved past the point where racism and targeting ethnic groups is no longer a ‘serious’ concern? We are all equal now, aren’t we?

Looking Like The Enemy provides timely context to remind us about the reasons why it is important to appreciate (kansha) all that has been done by so many before us, for our sake. Is it really necessary to remember and learn from our community’s experiences both before and after World War Two? Could the learning of this make us more complete, even ‘better’ Canadians? I, for one, will answer with an emphatic “Yes Yes” to both of these possibilities.

Looking Like The Enemy, Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, pp227. (2005). NewSage Press. $15 (US).

© 2010 Norm Ibuki