John Christgau had just finished his first book, a novel called Spoon, when he began to search for a good story idea for his next project. The resulting work of non-fiction, Enemies: World War II Alien Internment, was more than a good story, and the issues Christgau raised therein still resonate decades later.

Originally published in 1985, Enemies has just been reprinted with a new afterword by the author. The character-driven narrative features individuals of German, Jewish and Japanese descent. Especially since the events of September 11, 2001 in this country, identifying “enemy aliens” in the name of national security has once again lead to the victimization of ordinary people.

John Christgau had been especially interested in escape stories, so when his elderly neighbor reminisced about his war-time experiences as a guard at a prison camp in North Dakota, Christgau was immediately intrigued. The neighbor revealed that he had not guarded prisoners of war, as Christgau assumed, but rather German aliens at Ft. Lincoln Internment Camp. And yes, there had been an escape. “My interest was at two levels, not just as an exciting story. I was also interested because I recalled stories from my grandfather,” said Christgau, recalling the family tales of prejudice and hysteria that circulated in the German community of southern Minnesota where he was born. Although Christgau recalled the portrayal of Germans as victims of ethnic hysteria in the 1955 movie East of Eden, these injustices leveled at German aliens during World War II had not yet been widely written about.

Starting in 1979, Christgau tracked down stories of a number of Ft. Lincoln prisoners through oral history interviews and numerous boxes of government records held at the National Archives. One of his [qualifier] subjects was Dr. Arthur Sonnenberg, a German national who had emigrated to the United States in the 1920s. A physician in Germany, Sonnenberg had passed the California State Boards, set up a practice in San Francisco, and in 1938, applied for U.S. citizenship. Nonetheless, FBI agents arrested him on December 8, 1941 and he became one of the 31,275 prisoners of the Enemy Alien Internment Program.

Christgau’s research led him to a personal interview with another former prisoner of Ft. Lincoln. Hironori “Hiro” Tanaka was a Japanese American Kibei. Born in California to immigrant parents, Hiro had been educated in Japan before returning to his family in the U.S. Kibei, even more so than other Japanese Americans, were presumed loyal to Japan regardless of citizenship or residency, thereby considered a threat to national security. Hiro did, in fact, renounce his American citizenship but like many others, he did so in order to keep his family together if repatriated to Japan. It would be many years before the resolution of Hiro’s case, allowing him to remain in this country.

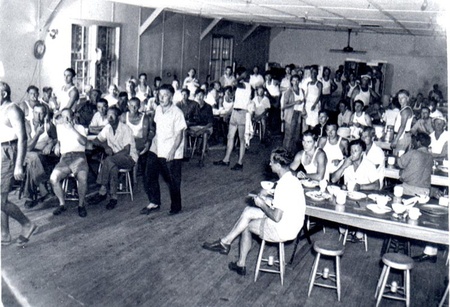

The first Japanese internees at Ft. Lincoln were aliens mainly from the Terminal Island area in Los Angeles. Arrested December 7th and 8th, 1941, they were sent across country in prison trains, and unloaded under armed guard at Ft. Lincoln, December 18, 1941. Photo from the John Christgau Collection.

Non-Japanese, however, have long argued that the Japanese did not have a monopoly on ethnic oppression. The German American Internee Coalition made up of World War II internees and their families charged that the presumption of disloyalty based on ethnicity affected them, too. Although, only Japanese Americans were forced to sign loyalty oaths, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 continued to have a sweeping impact on all persecuted ethnicities. John Christgau maintains, “if we ignore the injustice they [Germans] suffered, then we miss the impact of how wide the dragnet really was that affected so many innocent people.” While a very small number of suspected foreign operatives warranted legitimate concern for national security, prejudice and paranoia produced internment policies that conflated enemy nation with enemy race, making evidence of wrongdoing irrelevant.

That innocent people suffered displacement, separation from family and often, financial ruin was clear. But the prisoners of Christgau’s Enemies also suffered from gitterkrankheit. Christgau defined gitterkrankheit, German for “fence sickness,” as “what you feel after you’re behind bars. You feel you’ve done something wrong even if you haven’t.” The guilty feelings of the innocent made the readjustment process once released even more difficult for these prisoners.

The prisoners of Fort Lincoln, like those at dozens of internment facilities were mostly resigned to injustice. However, at least one notorious prisoner was the subject of an escape story that Christgau had initially sought. Karl “Fred” Fengler, born in Germany, emigrated to the United States in 1933. Within a year, he was convicted of shooting a car salesman while trying to steal a car during a test drive. Deemed “unstable” by a prison psychiatrist, he was arrested upon release from prison and transferred to Ft. Lincoln. The story of Fengler’s escape and subsequent capture four months later was a fascinating departure from the unwarranted suffering of the other internees.

Ft. Lincoln Internment Camp, Bismarck, ND August 24, 1943. Left to right: Chief Internal Security Off. W.C. Robbins, Op. Advisor E.E. Salisbury, Asst. Comm. for Alien Control W.F. Kelly, Comm. of I & N Earl G. Harrison, Director of Alien Enemy Control Unit Edward J. Ennis. Entering scullery on inspection trip of the Ft. Lincoln scullery, beneath which the escape tunnel began. Photo from the John Christgau Collection.

After years of research and writing, John Christgau’s Enemies finally made its way through the lengthy process of academic review typical of university presses, and was published by Iowa State University Press in 1985. But of that first edition of Enemies, Christgau said, “I was way ahead of my time and nobody gave a damn.” The subject of alien internment, perhaps because of lingering racism, did not receive a great deal of attention, and the book eventually went out of print. A few years later, however, Christgau started to receive letters mostly from daughters of German internees engaged in family research. Those inquiries prompted him to put the book back into print. But the event that brought Enemies renewed interest on a much wider scale was the bombing of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Once again, intolerance was on the rise, this time towards the Muslim religion and its adherents, regardless of nationality.

Several years ago, dissenters of America’s “war on terror” alleged that the United States government eliminated vital Constitutional protections for its citizens and unevenly applied the standards delineated by the Geneva Convention agreements towards enemy detainees. Policies that allowed racial stereotyping and the indefinite detainment of foreigners without charge illustrate the continued relevance of Enemies. Historian Arnold Krammer believed that “the arrest of thousands of noncitizens on mere suspicion of potential danger caused a crack in the Constitution that allowed McCarthyism and the communist witch hunts of the late 1940s and early 1950s.” The repetition of prejudice towards many based on the action of a few continues today.

It is because of this current political climate that the University of Nebraska Press approached John Christgau about reprinting of Enemies: World War II Alien Internment in 2009. His new afterward includes recently uncovered stories of unjustly-designated “alien enemies.” He also addresses his concerns about growing religious intolerance and prejudice towards the Muslim community. Says Christgau, “the issue has not become less important but rather more important. If there’s anything I can do to bring this important subject to a wider audience, I’ll go anywhere, any time, any place.”

* * *

Christgau is a prolific and prize-winning author of many books including Kokomo Joe (Nebraska 2009), The Gambler and the Bug Boy (Nebraska 2007), and The Origins of the Jump Shot: Eight Men Who Shook the World of Basketball, available in a Bison Books edition. His 1985 monograph, “Collins Versus the World: The Fight to Restore Citizenship to Japanese American Renunciants of World War II” appeared in the Pacific Historical Review (University of California Press.)

© 2010 Japanese American National Museum