As mentioned in “Amache Arrival”, our father, Sam Masami Ono, 29 (a San Franciscan) and George Dote (a Los Angeleno), were both released February 10, 1943 from Amache, the Colorado War Relocation Authority camp near the small town of Granada, Colorado. They were invited to go to Denver to audition/interview for translation and broadcasting jobs with the British Political Warfare Mission (BPWM). The British agency partnered with the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) in a “Joint Anglo-American Program of Radio Propaganda Program,” to broadcast to war-enemy Japan. The OWI had a staff of up to eight Japanese Americans. The BPWM had only four.

In the letter inviting Dote and our father to come to Denver and audition, it basically stated, “Be prepared to stay, if hired.” They were hired and were joined with Gish Endo out of Heart Mountain, Wyoming and Frank Hattori from Minidoka, Idaho, recruited from those WRA camps to complete the BPWM team with their British supervisor. Denver was chosen because Japanese Americans were not permitted on the West Coast, especially in San Francisco, where the OWI had initially established a broadcasting studio before the start of the war.

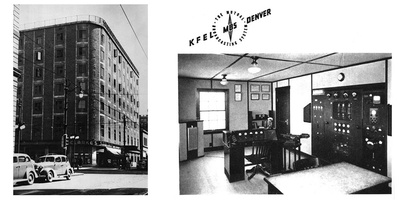

They were all Kibei, (Nisei, partially educated in Japan), with one exception, Chiyo Wada, a San Francisco Nisei who was studying Japanese language at UC Berkeley. She was also the only woman (#2 in group picture below) hired in either group. The OWI and the BPWM shared the KFEL Radio Station facility and engineers in the Hotel Albany downtown and took different shifts working around the clock translating news and other war information into Japanese and then broadcasting that material through the San Francisco broadcasting studio operation that packaged fuller programs by editing in music to broadcast to Japan over the short-wave radio signals.

Contrary to what Japan’s Radio Tokyo was doing with “Tokyo Rose” and the “Zero Hour,” the OWI and the BPWM always told the truth. Although, it can be said that careful editing and omission was commonly practiced, so that only what the Allies wanted broadcast was transmitted. The British group broadcast names of Japanese POW, while the OWI policy forbade that practice; otherwise their programs were similar.

The radio broadcasters and their families lived fairly well in Denver because their pay of $200.00 per month was very good for those days! In contrast, the internees—professionals, skilled labor & unskilled laborers—were earning $19.00 to $12.00 in the WRA camps. Except for occasionally being un-served by some businesses based on race, the broadcasters and their family enjoyed the parks and other entertainment amenities and most businesses of Denver. However, they were cautioned by their supervisors not to talk about the work they were doing.

Chiyo Wada told of an experience she had:

I was in the Albany Hotel elevator inside by myself when the door opened and a Caucasian woman and two gentlemen were about to enter. All of a sudden this woman said, “I can’t go in there.rdquo; And she said something in another tone “Irsquo;m not going in there with that woman in there.rdquo; I assumed because I was Asian or she assumed I was Japanese, I don’t know.

Many of the broadcasters, including my father, learned to play golf taught by Frank Hattori from Seattle and almost all of them continued playing long after the war ended ‘til they were into their eighties. Gish Endo, into his nineties today—and that’s his age, not his golf average!

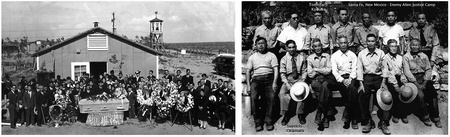

In this group photograph taken at a picnic outing, the OWI and BPWM employees and their family and friends are shown enjoying a day at the park. I believe this was taken before my mother, brother, sister and I joined our father in Denver, placing the date of this photograph before July 1943. My father is number 4, Gish Endo (#6) and George Dote (#20). Two were KFEL Radio Station employees (#7 & 10). Chiyo (Nao) Wada is number 2.

Click to enlarge: 1. Akira George Yoshida, OWI; 2. Chiyo (Nao) Wada, OWI; 3. Robert Tetsuro Yamasaki, OWI; 4. Sam Masami Ono, BPWM; 5. Hisako Nonaka, (F) (Family or Friend); 6. Gish Takeshi Endo, BPWM; 7. "Andy" Anderson, KFEL Radio Station, Eng.; 8. Shirow Uyeno, OWI; 9. Hiroko Baba, (F); 10. Mark Crandall, Mutual Broadcasting Co.; 11. Takehiko Yoshihashi, OWI; Toshiko (Sagimori) Yoshida, (F); 13. Patricia Yoshida, (F); 14. Frank Shozo Baba, OWI; 15. Kiku Yoshihashi, (F); 16. Spencer Baba, (F); 17. Fumiye (Nishida) Baba, (F); 18. Kimiye Okubo, (F); 19. Tommy Hamai, (F); 20. George Yasuo Dote, BPWM; 21. Kathryn (Dote) Hamai, (F); 22. Chiyo (Nonaka) Yoshihashi, (F); 23. Grace (Hamai) Uyeno, (F).

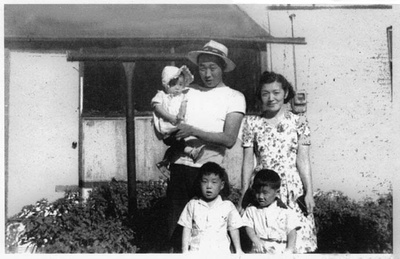

On June 8th, 1943, Uncle Hiroshi Okamura, 27, the eldest son of our mother’s siblings died in the Amache hospital as a result of injuries sustained in a canal construction accident. He is seen in this Amache family photograph with wife, Dorothy Yoshiko, holding Yaeko Phyllis, 2-1/2 and son Hiroichi Kenneth, 3-1/2 stands before his dad. Just one month following his death, Carol Hiroko was born on July 5, 1943.

Hiroshi’s father, Suyeichi Okamura, 57, who had been arrested Dec. 8, 1941 was released from the Santa Fe, New Mexico Enemy Alien prison camp (R) to attend the Amache funeral (L). He had not been seen by his family for over a year and a half! My father is in the photograph (L - near doorway, holding me), so he must have been given leave from his Denver job to attend the funeral. This barrack in Block 12G was the Buddhist Church located on the mid-southern edge of Amache. Notice one of the guard towers. Amache had the distinction of having unique octagonal shaped guard houses with eight windows.

According to WRA records, my mother, brother, sister and I were released from Amache on July 1, 1943 to join our father in Denver, so I would guess that was shortly after the funeral. Our grandfather was sent back to Santa Fe to further grieve, alone. (He is seated second from left) His eldest son Hiroshi was operating the family Cortez farm before the war, so Jiichan had to decide who would do so after. He was eventually paroled to rejoin his family on January 30, 1944. By then, two of his sons joined the US Army and another went to work as an auto mechanic in Chicago. Jiichan’s wife, Owai; daughter, Yuki, 24; and the youngest son, Togo, 12, were all that remained of his direct family in Amache.

Initially, our Ono family moved to 1521 Curtis Street in an active movie theater district. We lived in a walled-off area in the balcony of an older theater, where through a separation in the partition we could see movies playing. Later, we are shown in front of a house we moved to on E. 32nd Avenue near downtown Denver. At about this time, my mother required surgery, details of which I have none.

Amache WRA records show that our grandmother, Owai Okamura, 51, was released from camp October 24, 1943 to travel alone to Denver to help care for us children. Bachan Okamura who had medical problems of her own is shown (center picture below) near her barrack 6B, Block 10E. An Amache doctor’s letter indicated she had high blood pressure and a hernial condition.

As mentioned in “Amache Arrival,” on May 27, 1944, my mother, 26, gave birth to a new brother, Victor Katsumi in a Denver hospital. Unfortunately, she was diagnosed as having tuberculosis and when Victor was only a month-old, our mother was quarantined to a TB sanitarium in Boulder, Colorado. We children had to be cared for by our grandmother Owai and auntie Yuki again. Infant Victor was placed in the care of our paternal grandparents (L), Kinsuke, 69 and Kotora, 63 who lived in block 12F in Amache. They were from Graton, near Sebastopol, California.

I now realize that many of the Amache pictures of us children were taken and sent to my mother in the sanitarium in Boulder. L-R below: Cousin Yae Okamura, Gary, Sandra, Stanley & un-ID friend; Sandra & Gary; Block 10E kids with Margarette Masuoka, 14. She is the youngest and only girl of seven siblings of the Masuoka family. Margarette became the sister-in-law to our auntie Yuki (Okamura) Masuoka.

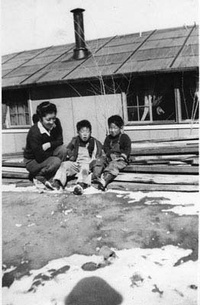

About 5 months later, much rested and healthy again, our mother rejoined us in Amache. Notice the patches of snow on the ground and my mother folding her arms to keep warm.

Our father continued to do his broadcasting work for the BPWM and near the end of WWII, the Denver radiobroadcasting program was shut down and the whole OWI & BPWM Staff was transferred to the San Francisco operation in February 1945, where the broadcasting effort focused on encouraging Japan to surrender. We joined him in San Francisco in the late spring of 1945, before the end of WWII.

Then, in August, the horrific nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which some argue hastened the end of the war. I think maybe the Hiroshima bombing would have accomplished that, but not the additional bomb dropped on Nagasaki. That, I and many believe, was a ghoulish scientific experiment to test a different type of nuclear device.

I think the memories of the attack on Pearl Harbor, her father’s arrest, World War II, the death of her brother in Amache, her illnesses in Denver and the nuclear bombings of Japan were placed in a box high and hidden on a dark distant closet shelf by my mother. She, like many others, didn’t talk about those dark “camp days” until the 1980s. Who can really blame her?

© 2010 Gary T. Ono