R. Buckminster Fuller once wrote, “Dare to be naive.”

In these days of non-stop irony, cynicism, and the constant overwhelming evidence that the fix is in, that we’re all screwed, screwed in ways we can’t even imagine, it’s hard to be willfully naive, especially since it’s so uncool.

When we first started talking about the idea of doing a staged adaptation of NO-NO BOY (playing at the Miles Memorial Playhouse Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays until April 18, 2010—please visit nonoboy2010.com for more details), there were some who warned us that we’d have a hard time getting support from some of the Japanese American institutions and community organizations for which this subject was still a painful one. Part of the reason we wanted to do this adaptation was to heal what we saw as a sort of hidden rift in the community, though some argued that the veterans would never come to a play called NO-NO BOY, and some of the draft resisters and No-No Boys themselves were not necessarily fans of the book, so there was a chance that the only people who would come would be a younger audience who saw the book as literature rather than a disputation of fact. We could do this project on its artistic merits alone but we had a greater hope, perhaps a naive one: That a play could actually promote healing.

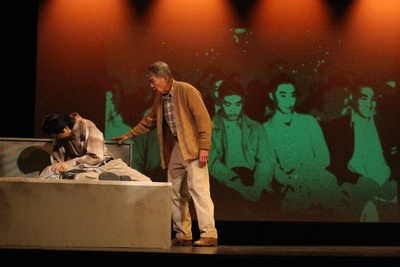

Keiko Agena and Greg Watanabe from production of NO-NO BOY. Photo by Emily Kuroda, courtesy of Ken Narasaki.

One can reasonably argue that the Nisei soldiers who threw themselves into suicide missions were naive to think they weren’t simply being used as cannon fodder, but one would be wrong: So many of them were like my father, who considered that possibility, but rejected it, deciding that this was the chance he was willing to take for his family here in this country.

One can reasonably argue that the No-No Boys and the draft resisters were naive to think that their stand, their statement, could possibly make a difference when the odds were already so stacked against them: Public opinion, which had already been manipulated to the point where the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese American men, women, and children was deemed necessary despite the fact that it went against the very principles this country was founded upon; a war that is still looked upon as the last “good” war where the enemy was clearly evil and the Allies were clearly good; and a community in which one of the guiding principles was “The nail that sticks its head up gets pounded down.” But again—one would be wrong. It may have taken decades, and the split in the community certainly is far from healed, but more and more people are looking at history, looking at the statements made by the ten percent of draft age men who either refused to sign the loyalty oath or refused the draft, and understanding that the ones who refused to fight also served the cause of liberty.

One can reasonably argue that it is foolish to think that this split could ever be healed: After all, most of the people old enough to have either fought in the war or refused to assent to Questions 27 and 28 are either in their 80s and 90s or are already dead. The common wisdom that we encountered in trying to address this subject has been this: You won’t get funding. You won’t get an audience. You won’t get support from the community which still regards this subject as an untouchable third rail. Luckily for us, we did get funding from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program; we got support from community partners Keiro Senior Health Care, The Rafu Shimpo, the Japanese American National Museum, East West Players, and the Tuesday Night Project, not to mention Discover Nikkei. We’ve also got a pretty dang healthy audience with a sold-out opening weekend, sold out matinees, and a run that’s approaching 75% sold. We also got the support of numerous artists who worked for far less than they were used to getting, with far smaller budgets, or playing far smaller roles, simply because they believed in this project. In other words, so far, our naivete is paying off.

I want to honor my parents, who were among the people who went willingly to the internment camps, believing it was their duty as Americans to go along with what their country told them to do. I want to honor my father, who risked his life in the 442 because this was his country, right or wrong, and he believed that he owed his country the ultimate sacrifice if that’s what they asked him to do. I want to honor the guys who risked everything, including their place in their community, for a principle, one of the bedrock principles upon which this country was founded: Civil disobedience. I believe this play is doing all of that by showing a cross-section of characters with differing emotional responses to a world gone crazy. I believe this play honors the veterans by giving voice to the principles for which they decided to fight, and I believe this play honors the draft resisters and No-No Boys by giving voice to their thinking as well as dramatizing the ostracism felt by many. Still, the question of whether or not a play can promote healing when the wounds themselves are over 65 years old is an open one.

Is it naive to hope for this? Then I have plenty of proof in my own heritage that it’s worth it to dare to be naive.

*Ken Narasaki is an actor/playwright whose world premiere adaptation of John Okada’s NO-NO BOY is currently running at the Miles Memorial Playhouse in Santa Monica (http://milesplayhouse.org/) Fridays and Saturdays at 8pm, Saturdays and Sundays at 3pm until April 18. Due to overwhelming demand for tickets, another show has been added for Sunday, April 11th at 7pm. This performance will be a benefit for the actors and tickets will be available at www.nonoboy2010.com.

More information can be found at www.nonoboy2010.com

© 2010 Ken Narasaki