In the spring of 1945, a young man showed up at Walt Disney Studios hoping to find a job in their animation department. He brought with him no experience to speak of, but a “portfolio” consisting of two notepads bought at the five-and-dime store, filled with drawings. The other men in the Disney waiting room with him were older, and carried large, impressive, black leather portfolios, but in the end, it was the inexperienced, young man who was taken in and given a job. This man, the 20-year-old Iwao Takamoto, began at Disney as an “in-betweener,” filling in the gaps between one animated pose and the next.

Within nine years, Takamoto had gone on to become the key artist in charge of Lady of Lady and the Tramp, and by 1969 he had cemented his status as an American legend with the design of the iconic character, Scooby Doo.

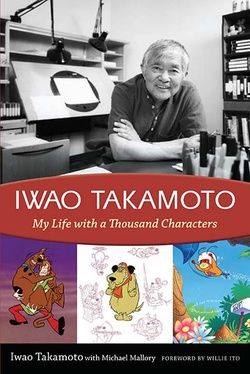

Takamoto’s autobiography, My Life with a Thousand Characters, co-written by Mike Mallory, documents his journey to prominence in the animation industry. This book chronicles his career from his humble beginnings at Disney Studios through his time at Hanna-Barbera, including his experiences working on such titles as Scooby-Doo, Where Are You; Jonny Quest; and Charlotte’s Web. However, this is not simply the story of a great creative mind. It is also the memoir of a Japanese American man who experienced life in one of the concentration camps of WWII, and went on to build a life for himself during a time of strong anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States.

In a way it was his time at Manzanar, a concentration camp located in the Owens Valley, about 200 miles northeast of Los Angeles, that led him to begin his career in animation. It was at Manzanar where he met Dr. Genevieve Carter, the educational director at the camp, who noticed his adeptness at sketching and gave him the supplies and encouragement necessary to improve his skills. He passed the time by sketching his impressions of camp at every opportunity. “Even without [Dr. Carter’s] encouragement, chances are he would have drawn anyway,” says Mike Mallory. “It was something that was within him. Iwao was like a photojournalist with a pencil; he loved watching people and capturing their attitudes and actions in a drawing.”

Despite the resentment that came with being forced to spend his teenage years in a concentration camp, Takamoto tried to make the best of his situation. “Iwao used to invoke the Japanese term, shikata ga nai,” says Mallory, “which he equated to something like ‘go with the flow’.” And all things considered, “going with the flow” seemed to work remarkably well for him. Apart from meeting Dr. Carter, Takamoto also encountered two men who worked as art directors in Hollywood. These men, having seen Takamoto’s sketches and recognizing his talent, encouraged him to consider entering the field of commercial artwork.

Once the war ended and all the Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated were released, Takamoto made a phone call to Disney Studios to request an interview. And the rest, you could say, is history.

At Disney, he found himself in the midst of an industry which he still knew very little about. However, he “quickly learned to learn,” he writes in his autobiography. It was maybe this enthusiasm, combined with his greenness, his “trainability,” as he puts it, that made him so appealing to Disney.

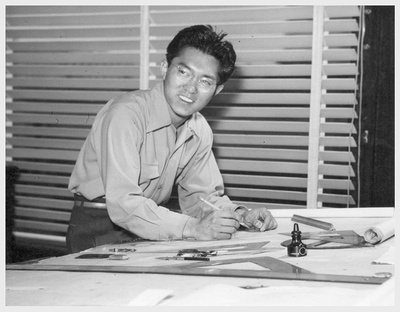

This photo of 20-year-old Iwao Takamoto, taken right after he had joined the Walt Disney Studios in 1945, was distributed to the Japanese-American internees to try and convince them that opportunity awaited outside the camps. Courtesy of Barbara Takamoto.

By 1960, a much more experienced Takamoto had left Disney and become the key studio designer for Hanna-Barbera. There, he worked on numerous shows, creating a wide variety of characters. “He strove to vary the graphic look of the Hanna-Barbera shows and particularly liked those that had a very distinctive design (such as Wait Till Your Father Gets Home),” explains Mallory, adding that “[he] was annoyed when people who hadn’t done their homework would refer to ‘the Hanna-Barbera look’, as though there was only one.”

Takamoto was a man who seemed to appreciate variety and well-roundedness. Says Mallory, “Iwao strongly believed that all artists should not only study art, but also history, literature, social studies, film… just about everything.” In fact, Mallory continues, “he could speak knowledgeably on virtually any subject, and with an understanding of it that was sagacious. I joked that after a while, our sessions together became less Iwao and Mike, and more like Yoda and Luke Skywalker.”

My Life with a Thousand Characters is a memoir peppered throughout with amusing anecdotes related in Takamoto’s direct and unassumingly humorous voice. On being called “legendary,” he writes, “I actually hear that word used in reference to me and, frankly, I often wonder what [people] are talking about. From the perspective of show business, which loves to pin labels on people, ‘legendary’ is a term that fundamentally applies to anybody who has managed to hang around for over fifty years. Since I am still hanging around and coming into work everyday… I guess I’ll have to bear up under the weight of the term.”

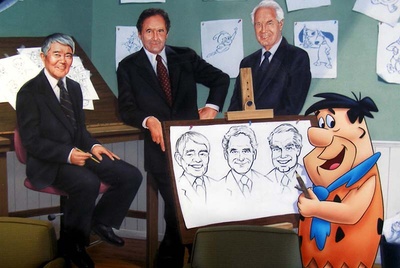

The key creative forces of Hanna-Barbera Studios: Iwao Takamoto, Joe Barbera and Bill Hanna, immortalized in a mural that adorned the Warner Bros. Animation building. Hanna-Barbera. All rights reserved.

Takamoto has become not only a legend, but also an inspiration. “Iwao Takamoto has left a legacy to the animation industry and also to the many Nikkeis who are following his path,” says Willie Ito, another Nikkei cartoonist, in his foreword to My Life.

As his autobiography was in the final stages of production, Takamoto suddenly died at the age of 81. “It was a shocking tragedy,” writes Mallory in a note at the beginning of the book. “But this book is not about sadness, since Iwao Takamoto was not about sadness. He was about joy and laughter and warmth and mirth and wisdom; he was a man who brightened the days of everyone who knew him… This is his story, in his words, and it remains as alive and vibrant as his legacy.”

“This was not simply the story of a great cartoonist, not just the story of a remarkable Nisei artist,” says Mallory, “this was the story of a great American life. I am thrilled and grateful to be a part of its telling.”

* * *

On Sunday, November 8, 2009, the Japanese American National Museum will put on a special one-day exhibition of Takamoto’s work. Mike Mallory and Takamoto’s wife, Barbara Takamoto, will be present to sign copies of My Life with a Thousand Characters.

* This article was originally written for the Japanese American National Museum Store Online in October 2009.

© 2009 Japanese American National Museum