On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which allowed U.S. military commanders to designate military areas as “exclusion zones” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” This action came two and a half months after Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack upon Pearl Harbor—the U.S. naval station in the Territory of Hawaii then home to the main part of the American fleet—which precipitated the United States’s entry into World War II.

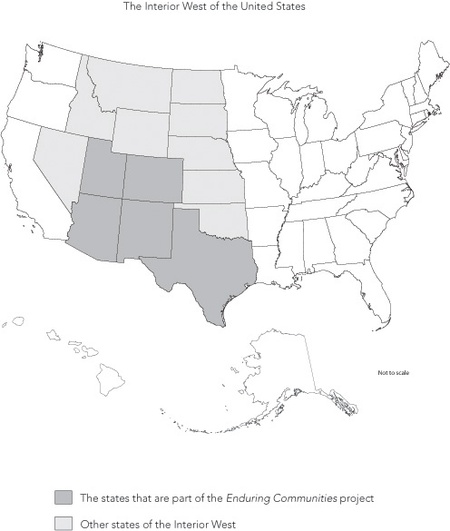

Although it did not specifically mention Japanese Americans, E.O. 9066 led to the decision by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, the Western Defense Command head, to exclude people of Japanese ancestry–both Issei (Japan-born aliens ineligible for American naturalization) and native-born Nisei, who were U.S. citizens–from California, the western halves of Washington and Oregon, and southern Arizona. Of the roughly 127,000 pre-World War II U.S. Nikkei (Japanese Americans), two-thirds were U.S. citizens and the overwhelming majority lived in the three excluded states bordering the Pacific Ocean. Approximately 94,000 Nikkei resided in California.

Initially, General DeWitt opted for “voluntary” resettlement: this allowed the “excluded” Nikkei to move—at their own expense—to any unrestricted area in the country.1 As a result, 1,963 people moved to Colorado, 1,519 to Utah, 305 to Idaho, 208 to eastern Washington, 115 to eastern Oregon, 105 to northern Arizona, 83 to Wyoming, 72 to Illinois, 69 to Nebraska, and 366 to other states (including New Mexico and Texas). There were many other potential refugees, however, who were thwarted in their attempts to move inland by the unwillingness of some states to accept them, difficulties in obtaining lodging and automobile fuel en route to their destinations, and upon their arrival, hostile “No Japs Wanted” “reception” committees, both public and private.

Consider the case of Clarence Iwao Nishizu, a 31-year-old Orange County (California) Nisei farmer. Having decided in early March 1942 that he preferred to have his family voluntarily move out of California and resettle inland, he drove his recently purchased 1941 Chevrolet to Colorado to check out possibilities there; he was accompanied by a younger brother, John, and a longtime Nisei friend, Jack Tsuhara. They were well aware that Colorado−thanks to the courageous civil libertarian commitments of its governor, Ralph Carr−and Utah (to a lesser extent) were the only western states willing to have excluded Japanese American citizens become residents.2

As restricted citizens under curfew on the Pacific Coast, the Orange County Nisei trio was required to carry travel permits, and they were not allowed to be out any later than eight o’clock in the evening. Before their early morning departure from southern California, they had heard rumors that no gas would be sold to Japanese travelers. After passing through Las Vegas on their first evening on the road, they were obliged to test the veracity of these rumors in the gateway southwestern Utah city of St. George. There, practically out of fuel, they stopped at the first filling station they encountered. It was closed, but when they saw someone sleeping inside the station they knocked on the door, and were greeted by a tough, burly man toting a shotgun, who growled: “What do you want?” To which Jack Tsuhara replied, “We’re out of gas, can you sell us some?” Surprisingly, the man responded in the affirmative. Relieved, and now with a full tank of gas, the pilgrims drove to Salt Lake City, via Vernal, Utah, where they bought alcohol for the car’s radiator to prevent it from freezing.

It was after midnight when the Nisei travelers crossed the state line into Colorado, after which they drove past Steamboat Springs up to the 12,000-foot summit of the Rockies. There it was snowing, a cold wind was blowing, and the temperature was 35 degrees below zero—and the water in the car’s radiator had completely boiled out. While the men initially contemplated filling the radiator with tea, they ultimate rejected this plan due to the tea’s high tannic acid content. Instead, they used a roadside cedar post to make a fire and so were able to melt snow for radiator water. With that problem solved, they continued their Colorado journey to Loveland and then on to Denver. There they succumbed in the early morning to their desperate need for sleep, only to be awakened by a policeman who inquired what they were doing sleeping in their car in the daytime. They replied, “Getting some rest after driving all night from California.”

Fortified with a letter of introduction from a produce shipper back home in southern California, the three Nisei went to see the head of a seed company in Littleton, a town south of Denver, and he kindly offered to let them stay at his home. After looking around Littleton, however, they realized that there was little hope of their families establishing a footing in that community. They then traveled to San Luis, Colorado’s oldest city, in search of suitable agricultural property to farm, but there they found nothing but alkaline soil, so they drove on to La Jara, a town near the Colorado/New Mexico border, to meet with one of the oldest pioneer Issei farmers in the state. Already reluctant to accommodate Nikkei “outsiders,” this patriarch apparently used the pretext of an earthy utterance by Clarence Nishizu, made in earshot of several of his ten daughters, to refrain from even inviting the three travelers into his home to discuss resettlement prospects.

After a visit to the alien internment center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to visit Issei relatives and family friends detained there, the three Nisei drove south to Las Cruces. There they met an Issei who was farming chilies—the crop their own families grew in the world’s chili capital, Orange County, California. Known as the “chili king” of Las Cruces, this Issei obviously feared potential competition and so offered his Nisei visitors no encouragement whatsoever to resettle in his area. Before leaving New Mexico, the threesome traveled west to Deming, a town they left in a hurry after an incident in a bar: an edgy local drinker inquired as to whether they were Chinese or Japanese, explaining, ominously, that “I can’t tell the difference between a [good] Chinese and a bad Jap.” Going next to El Paso, Texas, they met with yet another unfriendly reception, this time from the staff of the Chinese restaurant where they stopped to eat. Following a meal punctuated by shouts from the restaurant’s noticeably agitated personnel, the Nisei returned to their car, only to be menaced by the sight of a knife placed under a tire in order to puncture it.

Clearly it was time to return to California, but even as they attempted to get home the group met with further degradation. Driving through Chandler, Arizona, they were stopped by a state highway patrolman. After informing the Nikkei travelers that they were in a restricted zone, the lawman reminded them that there was a curfew in effect and asked if they possessed an authorized travel permit. When Jack Tsuhara flashed the obligatory document for inspection, the patrolman then patronizingly announced that they were headed in the wrong direction and smugly corrected their mistake.

In May of 1942, Clarence Nishizu’s family was detained first at the Pomona Assembly Center on the site of the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds; in August 1942 they were moved to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in northwestern Wyoming. At the time, almost all of the nearly 2,000 Nikkei in Orange County had been evicted from their homes and were incarcerated at the large concentration camp called Poston Relocation Center, located on Colorado River Indian tribal land in southwestern Arizona. After being declared ineligible for military service, in 1944 Clarence resettled with his wife, Helen, and their two young daughters in Caldwell, Idaho (near Boise), where he worked hauling potatoes. Around the same time, his parents and his two brothers, John and Henry, resettled in Ordway, Colorado, where they attempted to farm, unsuccessfully, on leased land. During the winter of 1945, with the West Coast now reopened to Japanese Americans, the entire Nishizu clan returned to southern California.3

NOTES:

1. See Janis Takamoto, “The Effects of World War II and Wartime Sentiment on Japanese and Japanese American ‘Voluntary’ Evacuees” (master’s thesis, California State University, Long Beach, 1991).

2. For a full assessment of Governor Ralph Carr’s actions in relation to Japanese Americans during World War II, consult the biographical study by Adam Schrager, The Principled Politician: The Ralph Carr Story (Golden, Colo.: Fulcrum, 2008).

3. See Clarence Iwao Nishizu, interview by Arthur A. Hansen, June 14, 1982, interview 5b, Japanese American Oral History Project, Oral History Program [Center for Oral and Public History], California State University, Fullerton. This interview was published as a bound volume (edited, illustrated, and indexed) in 1991 by the CSUF Oral History Program. For the resettlement narrative featured here, see pp. 142-44.

© 2009 Arthur A. Hansen