On a February morning when a faint hint of spring was in the air, a diverse group of Chicagoans gathered at the Indo-American Center on North California Avenue to discuss how attire and appearance impact the Japanese American and Asian Indian American communities. Present were representatives from the Field Museum, the Indo-American Center, and the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society.

This was the second planning session for Cultural Connections Program, a program administered by the Field Museum’s Center for Cultural Understanding and Change (CCUC). The CCUC brings the museum’s anthropological mission into the neighborhoods of Chicago by partnering with more than twenty ethnic museums and cultural centers. The theme for this year’s programs is “The Language of Looks.”

I was asked to join because in the twenty years I have been associated with the Chado Urasenke Tankokai Chicago Association, I have become adept at the arcane practice of wearing kimono. Our association consists of teachers and students dedicated to the study of Chanoyu, the Tea Ceremony. To that end, I have acquired a custom made, dark blue silk kimono with all the accompanying accessories. More importantly, I have learned how to wear it properly. My first thought on being asked was why not ask a Japanese-American male to model kimono? Little did I know that this seemingly simple question contained within it the basic conundrum of the entire program.

Although we were there to plan the event, I found myself in the midst of one of the best history classes I had ever attended. My fellow attendees commented not only on history, but also on demographics, anthropology, theology, philosophy, and no less important, fashion design.

I learned that Japanese history in the United States began with the Meiji period, some 150 years ago when Commodore Perry's “Black Ships” forced Japan to open its doors to the West. The first Japanese immigrants to America were farmers and agricultural workers. Their history in America was complicated by import quotas, exclusion laws, picture-brides and darkest of all, forced internment and resettlement.

This contrasts with the more recent history of an urban Asian Indian culture that migrated to America in the 1960s during the Cold War in response to a need for professionals, mainly scientists, engineers and doctors. They had the advantage of speaking English and being able to settle wherever the jobs took them. There was no need for them to be segregated into towns, as the Japanese were on the West coast.

Their disparate backgrounds have seen the Japanese strive for inclusion while the Asian Indian's inclination has been to blend and reshape American culture. To think of this in real-time, count how many women you have seen in sari versus kimono. It would be thousands to one.

The title of the program is “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall…How Am I Perceived By All?” As the afternoon proceeded, I watched various presenters discuss how history, politics, economics and culture play a role in how they dress as individuals. It became apparent that social status, gender, group affiliation, profession, values and taste all contribute to the every day decision of what to wear.

To complicate matters even more, all the above is dependent on the resources available to us. Our communities' accumulated knowledge and creativity combined to affect how we perceive ourselves and how we are perceived by the society at large. And you thought dressing for work in the morning was simple.

My experience prior to the conference had been with my colleagues in the world of Tea where not wearing a kimono is noticed more than wearing one. Individuals that revel in their ethnic dress have surrounded me and left me ill prepared for the numerous issues and the intensity of emotion related to dress. As culturally aware as I think I am, I am still a white male living in a world designed by and for white males, and before the Cultural Connections event I would have never understood this depth of feeling.

Part of our presentation was to demonstrate the complexity of dressing in kimono. In our casual age of buttons, zippers and Velcro, the art of dressing has been lost to most of us. Of course we learn to tie a scarf or a tie, but these pale in comparison to tying an obi.

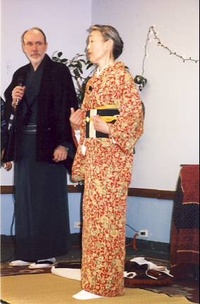

Joyce Kubose, a long time student and teacher in the Urasenke tradition of Tea, performed the seemingly impossible task of applying her obi in less than ten minutes. This task would take most of us not only much longer, but also would require an assistant. She perfected this skill while training at the Urasenke Headquarters in Kyoto for three years where kimono was the mandatory daily dress. Because of this unique experience, she differs from the vast majority of Japanese–Americans.

My initiation into wearing kimono began at the direction of Joyce Kubose, my tea sensei. She was the first teacher to encourage me to wear kimono. She understands that kimono is integral to the study of tea and not just a costume. I have become accustomed to and comfortable in my kimono and never forget that it is not a direct part of my cultural heritage, but a privilege extended to me by the Japanese-American community.

What is ethnic dress after all but cloth? It is just there, unless drawn attention to, as in couture. It is what grandma and grandpa wear, and what culturally aware youth use to play off of: sari with jeans and high heels, coats and accessories made out of antique kimono fabric. For most, ethnic dress is only brought out of the closet for important milestones: birth, coming of age, marriage and death. It is not a comfortable part of life for many people.

A perfect example of this was the story told by a young college-aged Asian Indian woman concerning nose piercing. Her mother was shocked to find out she had gotten her nose pierced while away at college, but her grandmother was so happy that she bought her multiple nose rings. It was as if her ethnicity skipped a generation before reasserting itself. Her mother had done what she could to fit in and her daughter had found a way to blend tradition with the fashion of the day to make a strong personal statement.

When I look out at the audiences that come to see us demonstrate the Tea Ceremony, I often wonder why there are not more Japanese-Americans, especially children, young adults and males, in attendance. Although this may be presumptuous of me to say, my wish for the Japanese-American community is not to deny, but to rediscover their ancient heritage. Ultimately I think this is the only path to inclusion.

So in the end what are we left with? Someone at the end of the program commented that the topic should not have been the Language of Looks but the Calculus of Looks because dress is the outcome of multiple variables. It is an adaptation, over hundreds of years by millions of people, in response to the world in which they find themselves. Sometimes they find themselves in favorable circumstances and sometimes in dire ones, but they are always looking to the future and to what will be the best for them and, more importantly, for their children, though they seldom realize this until they themselves are parents and grand parents.

* This article was originally publised in the Voices of Chicago by the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2006 Chicago Japanese American Historical Society