Today, Nikkei culture is as mobile as a newly-sown seed catching wind—any given location could be a potential homestead. The East and West coasts are like parental roots, foundations of communities in which Japanese Americans have found sustainable livelihoods. The Midwest and South populations are slowly on the rise. And the Japanese diaspora extends beyond US soil. For independent photographer Neal Oshima, planting himself in the Philippines has become more than a place of residence, it has become an inspiration.

Neal Oshima grew up in New York’s vibrant art scene in the 1950s and early 1960s. At the height of the Pop Art movement, Oshima would take a much different route to finding his passion in visual arts. He began in Connecticut at Wesleyan University, studying architecture, and then moved to Hawaii to attain a BS in Anthropology. Later he would relocate to California to attain a MFA in photography at University of California San Francisco.

At the age of 21, during his undergraduate work in anthropology, Oshima traveled through the Philippines, Europe, and Asia for one year. His bi-coastal and international experiences awarded him a wider perspective on photography and the rest of the world. Six years later he would became co-founder and principal photographer for the Shadow Visual Design Group in Manila. His combination of training in anthropology and photography, and the influences of Filipino culture, would resurface in his works for several years to come.

Recently, Oshima’s stunning photographs were reproduced in the book Dreamweavers, which captures the T’boli weavers of the Philippines. The weavers transform dreams of the past and present into tapestries called the T’nalak. In another publication, The Philippine Forest: Our Living Heritage, Oshima depicted the aesthetics of the surrounding culture and natural environment. The book won an Environment Award from the Manila Critics Circle. Last year his photographs were seen at the Museum of the Filipino People in Manila. The exhibition featured his photographs of the depletion of rice fields and farm life.

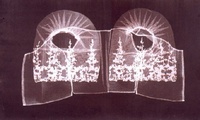

Sepia International, a gallery in New York City, mounted a stunning solo exhibition of Oshima’s work in 1999. The “Saya Series” included several images of traditional Filipino garments. The saya, a shirt typically worn by women and made from hand-woven natural fibers such as banana and pineapple plants, was worn by Filipino suffragettes before the arrival of the Spanish and Americans. Toward the end of the Spanish occupation, the saya became less common. When the Americans arrived, the saya was completely superseded by more modern, America-inspired clothes. However, the garment has remained a part of history, a powerful symbol of Filipino women and the resistance to colonial power. In the “Saya Series” Oshima captures a sense of history and emotion through these delicate images.

To provide some background on Filipino history, Japan occupied Manila and other parts of the Philippines for three years. The invasion began just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. During the Japanese occupation many people living in Manila were captured, murdered or placed in “internment camps.” While the Japanese military began organizing a new government structure, a massive underground Philippine guerilla movement was also forming. The US intervened and a major war ensued. Much of Manila was destroyed and more than one million Filipinos were killed by the time the Japanese surrendered at the end of the war.

Despite this history, “I have experienced very little animosity on the part of modern Filipinos towards Japanese or Americans and have never felt any hostility placed on my art due to my ethnicity,” Oshima said. A number of Japanese and Japanese American live in Manila; as of October 2000, 9,227 of the nation’s 76.5 million residents identified as Japanese nationals.

Neal Oshima’s photographs are similar to the way in which one may view a tree ring. The ring records a truthful yet beautiful depiction of a life that remains unseen. Oshima does not think of himself as being particularly Japanese American, but believes his extensive stays in Japan and South East Asia allow him to better understand his identity. His surroundings play a key role in articulating a visual language to speak of the discovery of self and history.

* Photo: Neal Oshima Photograph courtesy Sepia International

**This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage vol. XVI, no. 2 (Summer 2004), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2004 National Japanese American Historical Society