Read Part 1 >>

The Kubose Shumidan

The Kubose Shumidan, whose present home is The Buddhist Temple of Chicago, has a well-documented provenance. Gary Nakai, the 2011-president of the temple, said that the proper Japanese word for this altar is shumidan, not butsudan. Butsudans are enclosed in boxes, whereas a shumidan is a stand-alone altar.

This illustrates the difficulty of translating the English word “altar” into Japanese. See Figure 2 for a 2011 photo of the Shumidan.

A month after the October 1942 establishment of the Block-30 Nishi Honganji Church the Heart Mountain Buddhist Federation (Bukkyo Dan) was formed in Block 17.1 The federation included the sects Nishi Honganji, Higashi Honganji, Jodo Shu, and Nichiren. Of the ministers in the federation, Reverend Gyomay Kubose was the only one who spoke English. Reverend Kubose, a U.S. citizen, was of the Higashi Honganji Buddhist.

The building of the shumidan for the federation began on January 16, 1944, and was completed on April 1, 1944, with dedication on the next day. This provenance was recorded in kanji, using sumi ink, on the floor of the base of the shumidan by Reverend Masamichi Yoshikami of the Higashi Honganji Buddhists on the Japanese calendar date “Showa 19th year, 4th month, 1st day” (Figure 3). Witnessing this recording were Reverend Mohri, Reverend Kubose, Reverend Tatsuya Tsuruyama of the Nishi Honganji, and Reverend Kankai Izuhara of the Higashi Honganji.

Reverend Yoshikami also recorded other information – the names of the builders, sutras, and the eventual ownership of the shumidan. The builders were the skilled carpenters Suetsuna Okashima and Naoki Wakaye, members of the Heart Mountain Cabinet Shop, and an assistant, Tamiji Oshita. Important is the recording of the transfer of ownership of the shumidan from the federation to Reverend Kubose. With so many people of Japanese ancestry relocating further eastward, Reverend Kubose moved to Chicago at the end of August 1944 to minister in English and Japanese. After he had settled his family there, his shumidan was sent to Chicago.2

The wood used to construct the altar was not of high quality; it was essentially scrap lumber found in the Heart Mountain Cabinet Shop,3 but the craftsmanship is fine. The altar is approximately 6 feet tall, 5 feet wide and 4 feet deep. Figure 4, which shows Reverend Tsuruyama with the shumidan, gives a feel of the size. The curved roof panels (not visible in the photo) must have been made by steaming the wood. Unlike the box-like butsudans, which can be moved as a whole, the Kubose Shumidan had to be dismantled for moving. There are many parts, all numbered for ease of assembly and dismantling, which has occurred many times; in Chicago, the Shumidan has been dismantled and reassembled at least twice.

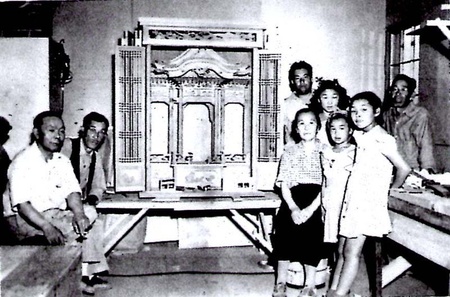

In the dedication photo (Figure 5), the builders Suetsuna Okashima, Naoki Wakaye, and Tamiji Oshita (born, respectively, in 1880, 1888, and 1868) are the people on the extreme right of the photograph, two seated and one standing. Very likely, Wakaye is standing and Okashima is seated at the far right. According to a newspaper article,4 they were presented with scrolls for their work.

Amida Buddha statues appear in Figures 1, 4 and 5. The statue appearing in Figure 1 was brought from the Yakima Buddhist Church and also appears in Figure 8 of the dedication of the Shibata Obutsudan. This statue was carried from one Buddhist church to another for ceremonial purposes, demonstrating its importance in the life of the Buddhists at Heart Mountain. The statues in Figures 4 and 5 are the same but not the one in Figure 1. This second statue’s owner is not known.

Reverend Kubose was interviewed in a 1996 Chicago PBS feature about the shumidan. The shumidan has suffered only slight damage over the years. In 2009 it was carefully repainted to preserve its original appearance, and placed in the Nokotsudo (columbarium) of The Buddhist Temple of Chicago (see Figures 2 and 3).5

The Aso Obutsudan

The August 21, 1943, issue of the Heart Mountain Sentinel newspaper6 reported that an obutsudan had been installed and commemorated by Reverend Chikara Aso on Sunday, August 15, 1943, at the Block-8 Nishi Honganji Buddhist Church. According to the article, the altar was 8 feet high and 4 feet 5 inches wide and built by Shinzaburo and Gentaro Nishiura and assistants Mankichi Matsukawa and Koichi Konishi (all four were members of the Heart Mountain Cabinet Shop). The article further noted that no nails were used [in the interior features]. The reported height of 8 feet is an exaggeration because it includes the height of the stand on which the obutsudan stood. In fact, the obutsudan’s dimensions are 51 ½ by 58 ½ by 30 inches. No photos of the obutsudan taken at Heart Mountain Relocation Center have been found. The image in Figure 6 is taken from a postcard advertising an exhibit of arts and crafts held at the Japanese American National Museum.7 For a very large photo of the Obutsudan, see Hirasuna, [pp. 104-105].

In the newspaper article, the Cabinet Shop supervisor gave the cost of building the altar: $73.24 for materials and $145.35 for 2 months and 2 days of labor at the $16 to $19 per month WRA wage scale. Unlike the Kubose Shumidan, which was made from scrap lumber and painted with opaque colors, the Aso Obutsudan was made from fine wood, which was bought in Denver and transported to Heart Mountain by Kiyoshi Nishiura, son of Gentaro Nishiura and a U.S. citizen, who had further relocated from Heart Mountain to Denver to work as a carpenter. The altar has a clear finish to reveal the fine wood. The design and construction of the altar probably started in May 1943 and was completed by August of that year. The obutsudan has a pair of three-paneled folding doors to close off the altar; one of the three panels closes a side of the altar, and the other two close half of the front. This is a much more elaborate pair of folding doors than the pair on the Horiuchi Obutsudan. The interior design of the Horiuchi Obutsudan is very simple compared to the temple design of the interior of the Aso Obutsudan. The temple design of the Aso Obutsudan is similar to that of the later constructed Kubose Shumidan; both required great craftsmanship.

From August 1943 to August 1945, the Aso Obutsudan was the altar at the Block-8 Buddhist Church. Reverend Aso returned in August 1945 to the San Jose Buddhist Temple, and the WRA eventually shipped the Aso Obutsudan to him for his personal home use. As the Buddhist population of the nearby farm town of Gilroy grew, Reverend Aso lent his obutsudan to the Gilroy Buddhist Church.8 The Obutsudan was donated to the Japanese American National Museum in 2001 by the Gilroy Buddhist Community Hall. It was the main atraction of the museum’s 2002-2003 exhibit “Crafting History: Arts and Craft from America’s Concentration Camps,” which was mentioned earlier. The obutsudan has suffered very little damage; only one of the circular lamps at the end of the hanging lanterns has been damaged (the circular lamps were not displayed in the exhibit).

The Shibata Obutsudan

The last and most elaborate of the four large Heart Mountain Center altars was built for Reverend Tesshin Shibata of the Nishi Honganji Buddhist Church. The location of the altar was possibly the Block-15 Church, although this cannot be confirmed. The order in which the altars were built is the Horiuchi Obutsudan, the Aso Obutsudan, the Kubose Shumidan, and the Shibata Obutsudan.

The start date of construction on the Shibata Obutsudan is not known, but there is a photo of it (Figure 7) in mid-construction with anotation by Shinzaburo Nishiura’s wife, Tani. She wrote that the photo of the almost completely finished altar was taken in July 1944. The four men in the photo were associated with its construction; from left to right, they are Choji Sakaguchi, Shinzaburo Nishiura, Shingo Nishiura, and Gentaro Nishiura. Shingo, son of Shinzaburo and Tani (who is also in the photo, immediately to the right of the altar), drew the outlines on the cylindrical columns and panels for the wood carvers; he was an instructor for the Art Students League of Heart Mountain.9 Tani identifies the children as having the surname Makiyama. The photograph does not include Fumiji Harazawa, who was a craftsman from San Jose involved in the building of altars, because he left for Utah two months before the photo was taken to be permanently employed.10 Choji Sakaguchi left Heart Mountain Center in late October 1945, also for Utah. From Utah, Harazawa and Sakaguchi later returned to San Jose to join the Nishiura Construction Company, which was restarted by the Nishiura brothers in early October 1945.

The next photo (Figure 8) shows the dedication of the obutsudan, which occurred during the April 7, 1945 festival day of Hana Matsuri. Standing are Reverend Tesshin Shibata and, on his left, Shinzaburo Nishiura.

The last photo (Figure 9) was presented to the Nishiura family by Reverend Shibata. Attached to the photo is a personal note in Japanese and dated “Showa 20th year, 1945, 8th month, 6th day.” An interesting aside is that the translator of the kanji signature of Reverend Shibata’s first name gave a name other than Tesshin (both names being correct); the translator was a young professor from Japan. More will be said about the personal note later.

The Shibata Obutsudan has two sets of folding doors, and there is a beautifully carved top panel. Comparing this altar to the Aso Obutsudan, one can clearly see that the Shibata Obutsudan is the more elaborate of the two, although both obutsudans are made with the same fine wood and finish. The exact dimensions of the Shibata Obutsudan are not known; it is probably a few inches taller and wider than the Aso Obutsudan.

Reverend Shibata was first relocated to the Tule Lake Relocation Center and then relocated once more to the Heart Mountain Center in 1943. Such multiple relocations were not uncommon – they occurred for many reasons – and must have been inconvenient, at the least. In October 1945, on the closing of the Heart Mountain Center, the Buddhist Churches of America assigned Reverend Shibata to a young Buddhist church in Ontario, Oregon, which was formed by Japanese Americans who voluntarily relocated away from the West Coast. He took his obutsudan with him to this newly formed Idaho-Oregon Buddhist Church and used it as the church’s altar. The obutsudan eventually became one for personal home use. The previously mentioned personal note from Reverend Tesshin Shibata to the Nishiura family concerned an announcement of the 13th anniversary of the death of his father, Reverend Eiju Shibata, who came to the United States many years before him to serve as a minister for the Buddhist Churches of America.11 Its present location is in Fukuoka, Japan as confirmed by Reverend Candice Shibata, grand daughter of Reverend Tesshin Shibata.12

Notes: (*The references occur at the end of the fourth part.)

- See Masuyama, page 15. The Block-17 Church became the Higashi Honganji Church of the Center after the Federation dissolved.

- See Kubose, page 59.

- For a photo of scrap wood collecting, see photo number 5 of WRA.

- Heart Mountain Sentinel, vol. III, no.14, Saturday, April 1, 1944, page 8.

- The two color photographs of the Kubose Shumidan were taken by Elizabeth Nishiura.

- Heart Mountain Sentinel, vol. II, no. 34, Saturday, August 21, 1943, page 2.

- Advertisement for Japanese American National Museum Exhibit: Crafting History: Arts and Craft from America’s Concentration Camps, November, 2002 – May, 2003.

- See SJBCB, page 53.

- Shingo Nishiura was an art instructor in the Art Students League of Heart Mountain, an offshoot of the Art Students League of Los Angeles during World War II. A 2008 exhibit at the Pasadena Museum of California Art included artwork from the Art Students League of Los Angeles; the exhibit included works of artists from this league who were interned in the Heart Mountain Center. Part of Shingo Nishiura’s portfolio was included; see PMCA for one of the paintings (page 92), and his biography (page 116).

- See AR3, where departure dates of internees from the Heart Mountain Center can be found. Further referencing of departure dates will not be made.

- See BCA for the Reverends Shibata’s history in the Buddhist Churches of America (in particular, pages 120, 130, 213, 242 and 251). Refer to page 396 for information about the third-generation Reverend Shibata.

- See “New BCA Minister Keeps The Faith, Seeks Outreach,” Nikkei West (November 17, 2015)

* Per the author's request, this article was revised on July 21, 2016; the revision includes new information provided by Patti Hirahara, donor of the George and Frank C. Hirahara Collection (see Figure 5 for a full collection citation.)

© 2015 Togo Nishiura