Who among us has not wondered if the World War II internment of the Nikkei community or, indeed, any other religious or ethnic one, could ever happen again?

It bears remembering that:

“Roosevelt had no qualms about discriminating against Japanese Americans. Although aware that some of his advisors felt strongly that Japanese Americans posed no threat to national security, Roosevelt personally harboured deep anti-Japanese prejudices and was convinced that the Japanese minority was dangerous. His prejudices—reinforced by the prodding of his Republican secretary of the navy, Frank Knox—would prompt Roosevelt to push for the internment of Hawaii’s 160,000 Japanese Americans until bluntly informed by his Chief of General Staff, General George C. Marshall, that neither Hawaiian nor Continental Japanese Americans ever posed a threat to American security,” from The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During The Second World War (1981) by Ann Gomer Sunahara.

And that, as a result of the Redress Movement the Canadian government in 1988 admitted:

“Despite the perceived military necessities at the time, the forced removal and internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II and their deportation and expulsion following the war, was unjust,” from The Government of Canada’s (Redress) apology.

It has undoubtedly been those similar “perceived military necessities,” that, in the aftermath of 9/11, have pushed the average number of immigration detainees being held on a given day in the United States from 6,785 in 1993 to 165,168 in 2002 to just under 400,000 under Obama.

Regardless of how one frames this reality, many argue that this is indeed another form of internment different only in how the lessons of the past, inform its application.

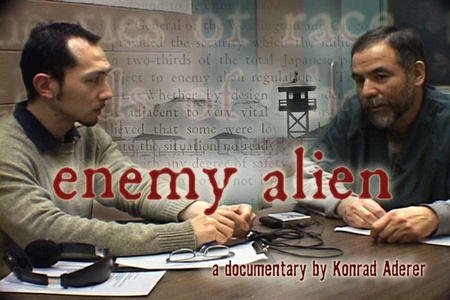

New York City-based filmmaker and social activist Konrad Aderer says, “Unlike my earlier work in this subject area, I chose to produce Enemy Alien as a first-person documentary because of the extent to which my subject, Farouk Abdel-Muhti, changed my life.”

“My sense of my own family history was transformed by today’s revival of national security profiling, but most of all by Farouk’s indomitable spirit of resistance to this injustice. As a teenager, when I first learned about the World War II internment of Japanese Americans, I was angered by the injustice of the U.S. incarcerating its own citizens, including my grandparents, because of their ancestry.”

“It wasn’t until after 9/11 that I gave a thought to the detention of non-citizens from countries with which we’re at war. Decades after its formal apology for the internment, the U.S. government used immigration law to target Arab and South Asian immigrants from 25 countries.”

But, he points out, “as I learned about the immigration detention system, the question of profiling any particular community gave way to the larger picture of deportation and detention of non-citizens of all national origins.”

Konrad confronts his family legacy of wartime incarceration as he joins the fight to free a Palestinian activist from Homeland Security detention.

The following is our interview conducted between January and February 2013:

Can you begin by telling us a little background beginning with yourself? Where did you grow up?

I grew up in New York City in the ‘70s, went to St. Luke’s, an Episcopal school in the West Village. When I was 10 I moved to Palo Alto, in the San Francisco Bay Area.

What did you know about the internment when you were younger?

In high school I was in a play about the internment, 12-1-A. I learned more from that play about the internment than I had previously learned in school or from my family. I liked my character, Mitch Tanaka, because he was angry about being incarcerated and he ended up going to Tule Lake. Projecting myself back in history I liked to think that I wouldn’t have been complacent, that I would have protested against the injustice of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans.

From childhood up through college my consciousness of being Japanese American mainly was formed through the sometimes negative or condescending perceptions of others about my Asian-ness. As a teenager I became singularly focused on being an actor, which gave me an ever keener awareness of my ethnicity as I navigated the gauntlet of stereotypes and limitations imposed on Asian-looking actors in the U.S.

Returning to New York to finish college and start an acting career, I found myself ghettoized and gradually brought into a community with Asian American theater and film artists in New York. This community sustained me as I transitioned into becoming a filmmaker. Through making Enemy Alien and sharing the completed film, my links with the Asian American community have deepened and broadened to include the West Coast.

Where did your mom’s family (grandfather Hiroshi Takayama) live on the west coast?

I never talked with my grandfather about Topaz, and he died in the ‘90s. Enemy Alien shows the first time I asked my grandma, Toyo, about her incarceration.

My grandmother was born in the U.S., and lived for a time in San Francisco and other places in the area. She spent some time in Japan and was on one of the last boats back to the U.S. before the war broke out. At the time she was staying with relatives in Pasadena, but somehow rejoined her Bay Area friends in Tanforan Assembly Center, where she was brought together with my grandfather Hiroshi, who had been a friend of her family before. She said they actually got married in Tanforan, which is pretty amazing to me.

What was their internment experience in Central Utah, Topaz, for three and a half years, like? Did they ever talk about it?

As incarceration experiences go, theirs was fairly stable and easy going as my grandma told it. She got to Tanforan after they moved incarcerees out of the smelly horse stalls the first ones had to live in, so she didn’t have to experience that. My grandfather did stay in one, but I never got to ask him how that was.

He was insulted at being discharged from the Army, in which he served shortly before the war, because of his dual citizenship. They started raising their first two children, including my mom who was born at Topaz. My grandpa had a job inside the camp, carpentry I believe. It seems to have been after the war that the injustice of the situation sank in for my grandma.

How do they feel about your exploration of your Japanese American identity?

I haven’t asked my grandmother about Japanese American identity, but she was supportive of my completing the film. She eventually decided she didn’t want to talk about the camps anymore because it upset her.

How does your father’s non-JA background factor into this?

My father is a veteran who joined the Marines to fight in Viet Nam. So I grew up familiar with plenty of ideas, attitudes, and words Asian American and other non-whites find problematic. I remember being a teenager when my white aunt would urge me to cultivate my Japanese background. I was bemused by that, and as I thought about it, irritated that others’ perception of my Asian face would obligate me to learn about Japan rather than Austria and England (my other countries of origin). But now I believe others’ perceptions is part of our individual and collective karma, and though there may be falsehood or injustice mingled with those perceptions, they’re part of our lot in life and our responsibility to work with.

How do you define “Japanese American” then?

I think the most progressive ethos today about identity is that everybody gets to choose their own, decide what it means, and form community with others who identify that way as they choose. The Japanese American community I know is contiguous with a broader Asian American community which works in solidarity to address the issues affecting Asians in the U.S.

© 2013 Norm Ibuki