Read Part 3 >>

“OI OKINAWA”

On most plantations, different nationalities were housed in separate camps Although they adopted one another’s food, clothing, and speech, the various ethnic groups did not socialize with one another. Even within the same ethnic group, a separation of sorts existed based on regional and prefectural differences.

Among the Japanese the greatest distinction existed between the Naichi, people from the main islands of Japan, and the Uchinanchu, people of Okinawa. The Okinawans were treated as outcasts and foreigners by people of other prefectures. “Our Japanese didn’t sound like their Japanese, so they constantly made fun of us,” recalled one Issei Okinawan. “They never called us by our names, but always by ‘Oi Okinawa.’”1 Separated from the mainstream of Japan, the people of Okinawa had their own distinctive dialect, music, dancing, martial arts, foods, and other customs.

Immigration from Okinawa began on January 8, 1900 when 27 men were allowed to enter Honolulu. Kyuzo Toyama, known as the Father of Okinawan Overseas Emigration, promoted emigrants to Hawaii as a solution to the enormous problems of Okinawa.

As the last prefectural group of Japanese to come to Hawaii, the Okinawans faced additional difficulties integrating into the established community of Japanese who were predominantly from the southwestern prefectures of Japan. Before Japanese immigration would terminate in 1924, 20,000 more would follow from Okinawa, making significant contributions to Hawaii’s development.2

“We, Okinawans, have a characteristic of not giving up,” explained a plantation worker about the Okinawan fighting spirit. “It was this characteristic that helped me to rise even when I lost. I never inherited any fortune. Only thing I had was a healthy body. So, it I lost…I just made up my mind to rise again.”3

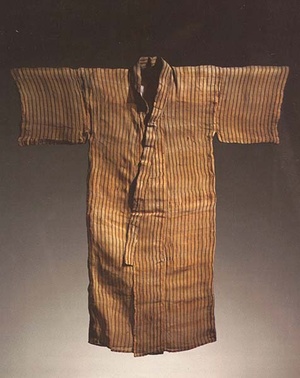

Okinawan Kimono made of banana fider ca.1900. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George Kiyoshi Sankey, Japanese American National Museum (91.7.1)

EXODUS TO THE MAINLAND

Contract labor ended with the annexation of Hawaii by the United States in 1898. With the workers now free to seek better opportunities, “American fever” gripped the Island. West coast labor agents, representing railroads, farms, and canneries on the mainland, scoured the plantations for possible recruits. “You can earn $1.35 a day on the mainland,” they promised, “double the amount you get paid as an ordinary plantation laborer!”

Recruitment ads announced: “Six hundred laborers for the Seattle-Tacoma area to depart June 19th.” Others exhorted: “Now is the time to go.” On the scheduled sailing dates, Honolulu’s 24 Japanese inns and hotels bustled with an overflowing business of migrants heading out.

The planters, who had predicted a labor exodus after Hawaii’s annexation, had imported more than 26,000 Japanese contract laborers in 1899. But the numbers were not sufficient to replace the estimated 40,000 to 57,000 Japanese who had gone to the Mainland via Hawaii over the next seven years.4

Alarmed by the mass migration, the planters, Japanese consular officials, Japanese community leaders, and the Hawaii legislature tried to stem the exodus. The Hawaiian legislature imposed a $500 license fee on labor agents recruiting for the Mainland, but all efforts failed.

Finally, on March 18, 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt signed an executive order prohibiting aliens (i.e., Japanese) “who had received passports to go to Mexico, Canada or Hawaii,” from migrating to the continental U.S. To insure the effectiveness of the Executive Order, the United States had received assurances from Japan to stop issuing passports to laborers destined for the continental United States. These negotiations, known as the Gentlemen’s agreement of 1907-08, stopped the Japanese exodus to the Mainland. Those who remained on the plantations struggled to improve their living and working conditions.

Notes:

1. Yukiko Kimura, Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii (Honolulu, 1988) pp. 74-75

2. Yukiko Kimura, “Social-Historical Background of Okinawans in Hawaii in Uchinanchu, 51-71.

3. Ibid, p.66.

4. Reports of the Board of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, January 1902-June 1910, in James Okahata, A History of Japanese in Hawaii, p. 162.

* Issei Pioneers: Hawai‘i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 is the catalogue accompanying the National Museum’s inaugural exhibition. Using artifacts from the National Museum’s collection to tell the story of the courageous “Issei Pioneers,” the catalogue focuses on the early immigration and settlement years. To order the catalogue >>

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum