Read Part 3 >>

After this case Marion’s services were in such demand that the majority of his practice was with the Japanese who were grateful to him for his interest in their welfare. Two actions which were forerunners of Marion’s most memorable legal victories were cases of escheat. This legal term has been used since the beginning of old English law. Escheat describes an action in which the governing body, in this case the State of California, takes over possession and ownership of property which the state claims has been illegally obtained by an individual or group.

The state, in the case of People vs. Nakamura, filed an escheat action against some farmers in San Diego County.1 The defendant, Mr. Shoichi Nakamura, was a citizen of the Hawaiian Islands, a territory of the United States at that time. Intricate legal issues were involved here such as the constitutionality of the provision that persons of Japanese ancestry had to prove citizenship to own land whereas other citizens did not. The key question of the case was whether an escheat was a criminal or a civil action. Wright, acting for the defense, contended that it was civil in form but criminal in substance. Therefore the defendants did not have to testify against themselves. The court agreed with this concept presented by Marion, and the description of escheat as being civil in form but criminal in substance was used as the basis for all further escheat proceedings in California.

The other case relating to escheat was appealed by the state to the Supreme Court of California. This was the State vs. Tagami in 1925.2 The state sought to escheat the leasehold interests in some property on the southern California coast which Tagami was using as a health resort and sanitarium. The state contended that under the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1911 and the Alien Land Law of California in 1913, this was illegal as the lease was not for “residential or commercial purposes” as stated in the law. The question in this case was whether these two existing laws, the U.S. treaty and the California Alien Land Law, should be interpreted strictly or liberally as Wright contended. The court chose a liberal interpretation. It decided that the operation of the sanitarium was within the meaning of the treaty and the state’s action for escheat was denied. Tagami could continue to occupy the land under the terms of the lease.

These decisions did not settle the question of Japanese citizenship nor did they address the question of the right of Japanese to own land in California. J. Marion Wright had more work to do.

As he approached the middle years, this lawyer kept busy with a diversity of activities. His law practice continued to grow. Individuals of various races came to depend upon this man of honest reputation for help. He not only practiced law but he used his legal training in community service. He was the lawyer for the Los Angeles Mission for many years; served on the board of the McKinley Home for Boys and was an elder in the Presbyterian Church. He was a member of the Glendale Board of Education for ten years. While on the board he became the organizer and first president of the Citizens’ School Council, a support group for the Glendale schools. Under his leadership the organization grew to a membership of 6,000 people. He had a long tenure as the attorney for the Shriners’ Hospitals for Crippled Children.

In light of his activity in civic affairs, he was persuaded to run for the office of District Attorney of Los Angeles County in 1932. This campaign took place during the unique time when prohibition was in force in the United States. Under the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, no liquor could be sold, consumed or possessed by anyone except for medicinal purposes. Candidates at that time ran on either a “wet” ticket, which supported repeal of prohibition or on a “dry” ticket which supported the status quo. Marion, who did not drink, ran on the “dry” ticket. The campaign was active and required many days and hours away from his law practice and family. He was defeated by the incumbent, Buron Fitts, a “wet.” Wright disliked campaigning so intensely that he remarked with vehemence and wry humor that he would never run again for anything, not even for dog catcher.

Even in frustration Marion could see humor. One of the Wright campaign managers was his friend, Will G. Fields, a Justice of the Peace in the Pomona area. After the election returns came in favoring Buren Fitts, and the heat of the contest had subsided, Marion enjoyed teasing Judge Fields by reminding him that there was not one vote for J.M. Wright in Judge Fields’ own precinct in Pomona! Where was the judge on election day?

As the pace of the law practice became more rapid and help was needed to handle the increasing workload, Owen E. Kupfer, a second-year law student, joined the Wright firm as a part-time law clerk and process server. In 1934 he passed the California State Bar and became Mr. Wright’s highly esteemed associate attorney. They worked together for over thirty years enjoying and appreciating the challenges of the legal profession.

In the fifty-seven years of his law practice Marion Wright had but two personal secretaries, Jeanette Quist and Janet Bement. Their skill and loyalty were legendary. Mrs. Quist traveled eighty miles a day for twenty-nine years from Pomona to Los Angeles on the Pacific Electric Big Red Cars until her retirement in 1942. Miss Bement drove daily from Newport Beach, a round trip of 120 miles. She was his treasured secretary for thirty-two years.

Marion distinguished himself as a member of the Board of Trustees of the American Bar Association for three terms (1932, 1943 and 1944) and was renowned for his skillful work as chairman of the Bar Association committee, which met with doctors to draw up areas of cooperation with the Los Angeles County Medical Association. The work of the committee under Wright was commended by the Bar Association.3 His understanding leadership brought about cooperation between groups which heretofore had worked at cross purposes.

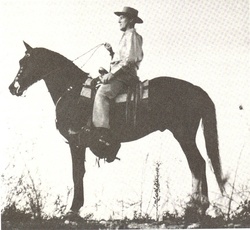

One of Wright's great pleasures was his ranch and a recreational ride on a favorite horse as in this 1946 photograph.

In mature years this able lawyer became Potentate of Al Malaikah Shrine, he added another dimension to his life, and to that of his family, by becoming interested in riding horses. What started in 1937 with a trot in the park on a gentle horse became an abiding interest and led to his roping cattle from horseback and learning the art of cutting calves out of the herd for branding. This marking of cattle is a legal requirement for selling cattle in California. In 1938 eleven acres of undeveloped land near Griffith Park became available. Marion bought the property as a place to keep the riding horses which he had acquired for the family. After World War II he and Alice built an adobe house and moved to the property which they named Pitchfork Ranch. Twice a year he staged roundups at which time all the unbranded calves, sometimes as many as twenty in a day, were stamped with the Pitchfork brand. This activity was accomplished with one or two experienced hands and many amateurs. Sons-in-law and other relatives and a large crowd of friends were the participants. There was much hilarity and hesitation as Marion always chose the most urbane and formally dressed lady of all to do the first branding. The one hundred or more guests gathered at the chuck wagon afterwards for a delicious and filling feast.

These activities with their western flavor were appropriate to the location. The property was a part of Rancho Santa Eulalia, an old Spanish land grant. It was adjacent to the Los Angeles River on which the city was founded and lay within the limits of the present City of Los Angeles. Marion was always fascinated with the history of the area and was proud to be a native-born Californian and Angeleno.

Part 5 >>

Notes:

1. People vs Nakamura 125 Cal App 268 13 P 85 1932.

2. State of California v. Tagami 195 Cal 522, 234 P 102 1925.

3. W.W. Robinson, Lawyers of Los Angeles (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Bar Association, 1959), pp. 288-289.

* “J. Marion Wright: Los Angeles’ Patient Crusader, 1890–1970” by Janice Marion Wright La Moree was first published in Volume 62, no. 1 (Spring 1990) of the Southern California Quarterly, then reprinted separately in a limited edition that same year.

**All photographs are courtesy of the author.

© 1990 Janice Marion Wright La Moree