Eighty years ago, the inaugural Nisei Week was organized in Little Tokyo in 1934. A distinctive Nikkei community event that was actually created as a marketing campaign, Nisei Week reflects the bicultural character of its founders. It has a parade that features ondo dancers (which explains why the parade with such a physically short route takes the hours to complete). It has a queen pageant where contestants wear kimono. Like its founders, Nisei Week’s resiliency is notable, having survived the World War II forced removal (including the abandonment of Little Tokyo) and changing tastes and attitudes. Certainly, one could not fairly detail all the remarkable aspects of this singular Japanese American festival in one article, but its continued existence with fewer and fewer Nisei is clearly one of them.

Groups from Japan often came to take part in Nisei Week. This Awadori group performing in front of Koyasan Buddhist Temple on August 25, 1968 came to dance at the festival. (Photograph by Toyo Miyatake Studio, Gift of the Alan Miyatake Family. Japanese American National Museum [96.267.1025])

Thinking about it, I am amazed at the audacity of the original organizers at arriving at the name Nisei Week. In 1934 in Southern California, most Nisei were still in public school. My mother was 14 and my father was 21. The oldest of their generation (a fairly small group) were probably in their 30s while the great majority of businesses, churches, temples, and community organizations were run by their immigrant parents, the Issei. Yet, they mindfully chose the name of Nisei Week. The equivalent would have been the Sansei, while most of us were still in college, telling our parents and grandparents that we were starting the Sansei Psychedelic Festival featuring Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, LSD, and Alice B. Toklas brownies while we protested the Vietnam War. (Okay, there is no equivalent in 1934 to that last part.)

Still, when you look at the actual history of Nisei Week, its creation was very rebellious. According to the official history written by the late Togo Tanaka, who was the English editor of The Rafu Shimpo before World War II, Nisei Week was developed in response to the fact that the “Issei controlled (Little Tokyo) completely, as they did the community. We respected our elders, but their ideas were getting old. Exuberant Nisei came up with the idea of Nisei Week to lift the gray cloud of the Great Depression. They urged the Issei to cater more to Nisei patronage both in hiring and retail practice. It was a milestone in Little Tokyo community cooperation.”

According to Tanaka, the Nisei, led by another of their organizations, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), were able to convince enough of the Issei merchants to support this new event that promised a full seven days of special activities and events that would attract more customers. “Nisei Week became an instrument not only to revive and revitalize Little Tokyo’s economic base,” Tanaka wrote, “but to expose the non-Japanese audience out there to the Nisei’s message that the successors to the Issei were a generation of Americans.”

The latter idea is fundamental to the Nisei generation, whose Americanism was constantly being questioned, even before the war. This explains why Nisei Week included so many American-styled events, such as a parade, a beauty contest, a carnival, a baby show, and assorted fashion shows, talent shows, and art demonstrations, albeit all with a Japanese twist. I also think it was no accident that words like Japanese or matsuri are clearly absent. Nisei Week was not a festival that the Issei would have organized.

I find it fascinating that after a seven-year hiatus beginning in 1942, Nisei Week was revived in 1949. The government’s illegal mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war had as one of its goals the ultimate dispersal of all Nikkei and the breakup of all Japantowns. That places like Little Tokyo were revived beginning in 1945 and an event like Nisei Week would be reformed is a demonstration of the resiliency of the Nikkei community surviving in an environment of overt prejudice. It is one thing to quietly organize Japanese language classes or to form judo clubs in community centers in the post-war. It is quite another thing to hold the Nisei Week parade two blocks from City Hall in downtown Los Angeles. Maybe this was more of that Nisei audacity that surprises me or maybe the strong Americanism theme built into Nisei Week was a way to show the greater society that Japanese Americans are real Americans.

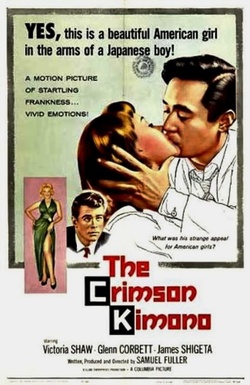

Certainly, both motives could co-exist along with other purposes. After all, Nisei Week did not just survive, it began growing in the 1950s. If you want a sense of what the Nisei Week and Little Tokyo was like in this era, watch the film, The Crimson Kimono (1959) by director Sam Fuller. While you rarely see this movie on television, it is distinguished by allowing a Japanese American detective (played by James Shigeta) to romance a Caucasian woman (played by Victoria Shaw), and by its backdrop: Nisei Week in Little Tokyo, where Fuller filmed much of his movie. The climatic scene has Shigeta’s character chasing the murderer through the Nisei Week parade, with the actual parade participants from 1958 in the background. It’s amazing to watch!

My first direct contact with Nisei Week took place when I was working at The Rafu Shimpo during summers while I was in college. I remember being assigned to cover the Nisei Week parade in the early 1970s. In those days, the parade was huge. They had a grandstand on First Street, near San Pedro, for the VIPs and those willing to pay to sit. Thousands of people turned out in those days and the carnival would attract Japanese Americans from all over Southern California.

In 1983, I remember eating lunch at the Mitsuru Grill counter, which used to share space with Kyodo Drugs on First Street. The proprietor, Lucy, made a face and then shot a glance to the other side of the counter. A Japanese man in a suit sat drinking iced tea. My initial thought was, “So what?” But finally Lucy whispered that it was legendary Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune (who starred in movies like Rashomon, Seven Samurai, Yojimbo, Sanjuro, etc., etc.). He had come to be Grand Marshal of the parade. Unsure of what to do, I went next door to Toyo Miyatake Studios and told Archie Miyatake that Mifune was next door. Archie came over and said hello. Mifune, in halting English, said to Archie, “Long time no see.” Having international movie stars as part of the parade would qualify in my book as pretty big, and at some point, Nisei Week was stretched to include two weekends.

I also think Nisei Week peaked around that time in terms of its overall draw. Attendance at the parade gradually declined and the carnival, which featured many community groups operating different games or food stands to fundraise, slowly lost those participants and their supporters. Some events evolved (the carnival became more of an outdoor arts and crafts gathering) and others disappeared (the talent show, long gone before my time). The Tofu Festival, organized by the Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC), proved to be a great draw to the wider community and a boost to Little Tokyo. But LTSC eventually decided it was too much work to put on. Most recently, the Koban and the Little Tokyo Public Safety Association (LTPSA) started its Tanabata Festival, which has created a new attraction.

Of the remaining core Nisei Week activities, what I find most interesting and most admirable is the development of the queen contest. The original Nisei Week Queen, Alice Watanabe, first crowned in 1935, was not someone judged the most beautiful or most poised by a group of celebrities and dignitaries, but was someone who received the most votes. Ballots were distributed by the Little Tokyo merchants, who would give them to their customers after they made purchases. The higher the purchase, the more ballots provided. (Remember, I said that Nisei Week was really a marketing campaign.) This system existed in the post-war until the 1960s, when it turned into a beauty contest, with judges and swimsuits and the whole nine yards.

After the U.S. women’s movement came into fruition, it was pretty clear that this sort of contest under this format was open to public criticism. In the 1980s, Nisei Week eliminated the swimsuit part of the contest, but it was some years before it evolved into something much more worthwhile: a program that emphasizes personal and professional development for its participants. I did not fully appreciate this fact until the last decade when young Nikkei women who I knew made it clear they wanted to be part of the Nisei Week court. These women were all intelligent, ambitious, and community-minded and I didn’t understand why they wanted to be part of what I considered an old-fashioned beauty contest (unless they wanted to be professional entertainers or something).

In reality, the Nisei Week Queen program today provides many opportunities for its participants to learn about their own cultural history as well as pursuing personal development in areas like public speaking, etiquette, time management, and networking. Candidates have the opportunity to travel and represent the festival and the Nikkei community. I was very impressed by the growth of the young women who became part of the Nisei Week court and am pleased that something that was seemed so dated has become something totally relevant to today. If you want a better sense of how the program has evolved, KCET’s Departures series interviewed several former Nisei Week Queens from the post-war era. It is illuminating. Go here: kcet.org/socal/departures/little-tokyo/round-table-discussion-five-former-nisei-week-queens.html

In the end, I believe Nisei Week still fulfills its original mission: to bring people to Little Tokyo. What has changed, I think, is that it no longer feels compelled to emphasize our Americanism. In fact, I think it has become one of the events where our Japanese American legacy is proudly displayed and shared with those within our community and those in the mainstream. Whether it is the Taiko Gathering or the Street Ondo or the car show, Nisei Week provides a strong platform for Japanese Americans to celebrate their history and cultural heritage.

© 2014 Chris Komai