My mother, Kinuko Saito, was holding me in her arms as we left Japan. I was six months old when we embarked on a military ship headed for Los Angeles via Seattle. Without knowing any English, my mother left her family and friends to start a new life in the United States. We had arrangements to stay with my father’s relatives whom she had never met before.

We patiently stayed and waited for my father to arrive; he was a G.I., a Nisei soldier serving in the United States Army. Before he joined the Army, he and his family were imprisoned at the Manzanar concentration camp in Independence, California during World War II. He answered the “Application for Leave Clearance” (loyalty questionnaire) with “yes-yes” while in camp so he could leave and work in Chicago. The city of Chicago would allow Japanese Americans to relocate from camp to work or get an education there. He was not allowed to go to the West Coast—that was off limits to Japanese Americans. He enlisted while he was in Manzanar after he returned from Chicago. He is bilingual so he was stationed in Japan during the U.S. Occupation.

When he was serving in Japan, he met my mother who was born in Hitachi, Japan. They got married by taking advantage of the Soldier’s Bride Act of 1947. It temporarily eased immigration laws that allowed Japanese women married to U.S. servicemen to enter the United States. My parents were married on August 12, 1947, just making the deadline. My father had to stay and finish his service in Japan before he could leave for Los Angeles.

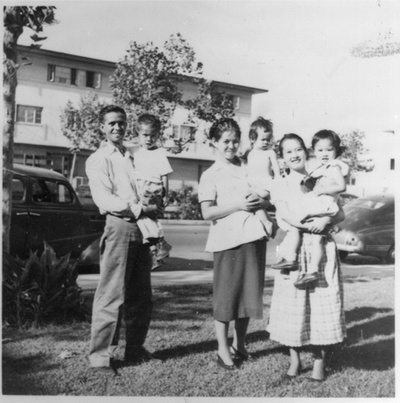

When my father did arrive and we were reunited, he moved from our relative’s home in Los Angeles and settled in Boyle Heights in the Aliso Village housing project on Mission and First Streets. After the war, the apartments had served as housing for servicemen returning home. My father, George Saito, was born near Little Tokyo and grew up in Little Tokyo and Boyle Heights near the location of Aliso Village. My mother and other “War Brides” from Japan also settled temporarily with their husbands in Aliso Village.

My mother formed strong bonds with the other wives, the beginning of lifelong friendships. The common thread among the women was they all left their families in Japan, married G.I. servicemen, had their children around the same time, and they only had each other for support.

Soon, everyone migrated to other parts of the city. One family moved to another area of Boyle Heights; another family moved to Harbor City. My family eventually moved to Los Angeles near Jefferson and Crenshaw Boulevards where my two sisters and brother were born.

One day, my father decided to move us to Torrance and grow strawberries. I really don’t know why my father decided to move. I remember our neighbors in Los Angeles saying we were moving to the “boon docks.” I asked my mother, “Where is the boon docks?” It sounded frightening to a young six-year-old.

Torrance was definitely in the boondocks, but I spent a wonderful childhood there with my brother and sisters. We all ran around freely, picking and eating strawberries, figs, and peaches. We had trees to climb—there weren’t many trees in Los Angeles. The fig tree was my favorite. It wasn’t too tall and was easy for a child to climb. I helped my mother by selling strawberries in our makeshift stand my father built. She would pick, meticulously arrange, and dust the strawberries with a feather duster that made them look so appetizing. Since we were a bit isolated on our small strawberry farm, my siblings were my playmates. There were frogs, tadpoles, lizards, snakes, and insects for us to capture. I am sure we would have never caught those in Los Angeles. The “boon docks” were actually turning into a fun place.

Coming from Los Angeles, where it is warmer than Torrance, my father always would say, “We don’t need air conditioning—we get the cool ocean breeze.” He would repeat that statement many times so it was embedded in my memory, but he was right, it was always comfortable.

We lived far from any Japanese markets, so my mother cooked everything from scratch. We were fortunate to have the “Fishman” as we called him. I think his name was Mr. Mano. He would come by and deliver Japanese groceries in his large van. He had fresh fish, Japanese condiments, tsukemono (pickles), and Japanese treats. We looked forward to his visits.

My mother did not drive, so it was convenient for her to have Japanese groceries delivered to our house. My mother would make tsukemono of various kinds. She would have a favorite rock—just the right size and weight—for weighing down the tsukemono as it was pickling. We were not allowed to play with her tsukemono rock.

One of my favorite tsukemono called nukazuke is fermented rice bran, no rock needed for this one. My mother placed various vegetables in the gruel-like mixture, and you had to mix it every day or it would start to spoil. Mixing the nuka was my job, not one of my favorite chores. I disliked doing it because, being a small child the crock was tall, and my arm was short. I was up to my elbow in nuka and the smell that it left on my skin was awful. But it is one of the best tasting and healthiest of tsukemono. I still enjoy eating it and when I find it at any of the Japanese markets, I always make sure to buy some. I did try to make it once before but it never was as good as my mother’s.

My favorite nukazuke vegetables were celery, carrots, and eggplant. If I removed and ate most of the vegetables, my mother would get angry and admonish me for not replacing the vegetables. She said, “There is nothing left,” and it would take a day or two to have nukazuke. I would then have to prep and replace the vegetables, then mix the nuka. Funny, though, how the lesson of replacing the vegetables in the nuka taught me to be more considerate of others.

I remember my mother telling me many times, “Family is very important—you can have friends but family will stick by you forever.” My mother said that because she is very close to her family in Japan. I remember my mother always telling me and my siblings, “Put yourself in the other person’s shoes,” and “Be kind to other people.” My mother always stressed strong family ties and that is why I think my sisters and brothers are all close.

My father is Christian and went to Union Church in Little Tokyo before WWII, and my mother is Buddhist. Our parents never stressed religion on us but I wanted to go to church. Our parents never stressed religion on us but I wanted to go to church. With the lack of transportation, I went to the closest one to my home so I could walk there and that was a Lutheran church across the street from my school.

Torrance had a good educational system and we all did well academically. I had great teachers and learned a lot from them. I still remember my teachers’ names—they had such a positive impact on me. My mother always went to my teacher’s conference because she wanted to know how I was doing in school.

I have learned a lot to live a good and healthy life because of my mother’s influence. She was the glue that kept us together and always sacrificed so much for us. She taught me to be proud of being of Japanese descent and always talked about her family in Japan. She talked about her mother and what her mother taught her, like sewing and cooking. She told us how kind and intelligent my grandfather was. I know those rainy day talks with my mother influenced me about strong family ties. They are our oral histories that will be remembered and passed on to our children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. My mother would tell us Japanese stories that had meanings to them so that we would learn good morals and to be kind to others. I enjoyed those stories—they were better than a book or T.V.

My mother cooked traditional Japanese dishes and always talked about the different foods of Japan. I think that is why I eat healthy foods and enjoy Japanese foods so much. We did make requests for American food like our school friends ate. She learned to cook some American dishes for us and did quite well. Our favorite American dish she made was potato salad, and we requested that for all our family potlucks.

My mother was a perfectionist like her mother and so our New Year’s (Oshogatsu) celebration food was to die for. She cooked for days, and she taught us how to cook some of the New Year’s staples. I was the one to chauffeur her around to all the local Japanese markets to shop for her favorite items. Our New Year’s was always looked forward to by our whole family for eating delicious Japanese food mom made and getting together. That was important to my mother and it made her happy to see us together and enjoying her food.

My mother had a stroke 11 years ago and could not cook anymore, so we were fortunate Mom had taught us the basics earlier so we can still make some of the New Year’s foods. Luckily my sister-in-law is an excellent cook and now does most of the cooking for our New Year’s. I am dedicating this story to my mother because she passed away on August 27, 2009. I miss my mother and I treasure every moment I spent with her. She was such a wonderful mother, and I was blessed to have her, thank you, Mom.

* This article was originally published in the Nanka Nikkei Voices: The Japanese American Family (Volume IV) in 2010. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2014 Marie Masumoto