Introduction

The Los Angeles “Little Tokyo” neighborhood, built by Japanese immigrants before WWII, is home to the Japanese American National Museum. Founded in 1985, this stately museum, consisting of an old and a new building, houses a variety of collections that document the history of Japanese Americans. Among the 20,000 stored items, 40,000 pictures, 150,000 linear feet of film, etc., is the collection of over 600 small stones that forms the subject of this paper.

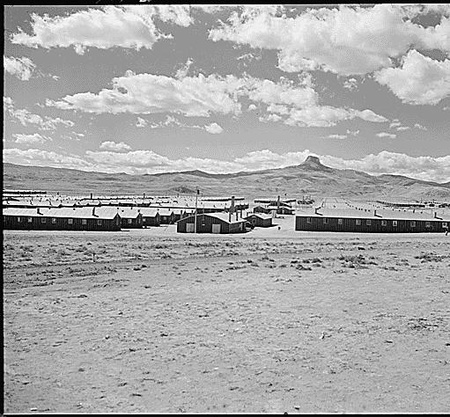

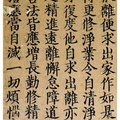

The stones, in various shapes, sizes (several centimeters in diameter), and qualities, each with a brush-written Sino-Japanese character on its surface, together constitute what I have here termed a “One Character per Stone Scripture.” The collection was unearthed from the cemetery site of the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, one of ten concentration camps where 120,000 Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans living in the United States were forcibly detained during the Pacific War (World War II).

I first saw this collection of small stones quite accidentally when I visited the museum in March 2001. At that time the collection was prominently displayed in an exhibition on the history of the strife and suffering of Japanese immigrants over the course of more than a hundred years. I skimmed some of the characters written on the stones and intuited that they must be part of a copied Buddhist scripture (sha-kyo), but I could tell nothing beyond that. Though the museum similarly did not know the nature of the collection, it was briefly reported at first in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly (Summer 1994). Over the years, the stones were featured on postcards and made into facsimile souvenirs, and the collection itself was regularly loaned for special exhibitions throughout the United States.

I visited the museum again in September 2003, with the purpose of researching this enigmatic collection. I began by copying all the characters appearing on the stones, taking statements from people familiar with the collection, and consulting related materials and collections in cooperation with the museum.

After conducting detailed analyses and investigations in Japan, I published the results of my study in an academic journal in March 2006. An enlarged and revised version of my thesis appeared in the Journal of the Research Society of Buddhism and Cultural Heritage, vol. 17, October 2008. It is titled “The Small Stone Scripture Preserved in the Japanese American National Museum: A Buddhist Artifact from the Cemetery Site of the Heart Mountain Concentration Camp (revised version)” coauthored with Prof. Kenryo Minowa. Those interested in the detailed report may please consult this paper. It is, however, an academic paper not meant for the general reader.

Because from the very beginning I wanted ordinary Buddhist in Japan and the U.S. to know the history of this important artifact, I subsequently contributed a general overview, in Japanese, to the Laymen-Buddhism, No. 679, December 2008. Now, an English version of the overview is made available here with the help of a translator.

In this paper I describe the circumstances of the Stone Scripture’s production and the method used to identify its text and the individual who created it. I conclude by providing a brief overview of the tradition of scriptural copying and burial, and I introduce three other modern examples of this picture.

The Heart Mountain Concentration Camp and Buddhist Activities There

Upon the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941, 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans living in the United States were arrested and detained in district collection centers, where they were then distributed among ten U.S. concentration camps. German and Italian immigrants, also from enemy countries, were not detained. More than 10,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans, most from the state of California, were detained in the Heart Mountain concentration camp (named after nearby Heart Mountain) in Wyoming. Until the end of the war in August 1945, they were forced to live extremely restricted lives in shabby barracks surrounded by barbed wire and tall surveillance towers.

Though the detainees were severely limited in entering and exiting the camp, they were provided with schools, hospitals, dining halls, and other public facilities, and they managed before long to create a semblance of autonomous life under the control of the government-appointed American concentration camp manager.

The state of Japanese and Japanese Americans in wartime concentration camps has been described in many published studies and reports in the U.S., but no detailed survey of the religious activities, especially Buddhist activities, in these camps seems available so far.

However, The Heart Mountain Sentinel, a newspaper published by detainees in both Japanese and English, provides a valuable glimpse of life in the Heart Mountain concentration camp. Published once or twice a week, the newspaper included public notices, messages, announcements of various events and meetings, information necessary for living in the camp, news, and descriptions of cultural and athletic activities.

In surveying the Japanese version of the newspaper’s articles and announcements relating to Buddhist cultural and religious life within in the camp, we observe that activities fall into two major groups.

The first consists of sectarian events and meetings organized by the detainees as revived and continued from their prewar lives. Buddhist sects with a presence on the west coast of the United States prior to the outbreak of the war included the East and West Honganji sects of True Pure Land Buddhism, the Soto and Rinzai sects of Zen Buddhism, Esoteric Buddhism, and the Nichiren sect. These sects had built their own temples and centers and endeavored to teach and transmit the Buddhist Way to Japanese immigrants.

As the teachers and followers of these Buddhist sects were detained together in the camp, they immediately resumed the events and activities conducted before their detainment. Amidakyo lecture meetings, Hokekyo (Lotus Sutra) lecture meetings, Grace Requiting Gatherings (Hoonko), Young Buddhist Association meetings, and Sunday Gatherings were, for example, periodically held among the various individual sects.

Buddhist activities in the second group, on the other hand, were run by a unified Heart Mountain Buddhist Association organized soon after detainment by teachers representing all of the sects. This organization mainly coordinated the Buddhist events and activities common to all the sects, such as the Buddha’s birthday (Hanamatsuri, Flower Festival), Ulambana (Obon: Ancestral Festival), and various thanksgiving ceremonies. The association was also responsible for cleaning the cemetery compound that was built by detainees on the west side edge of the camp.

As more than 10,000 detainees lived in the camp over the course of about three years, there were naturally births and deaths—according to a record, there were 552 births and 183 deaths during this period. The cemetery provided a final resting place not only for Buddhists, but also for Christians and Shintoists. Here, too, the Stone Scripture described in this paper was buried.

Discovery of the Stone Scripture And Its Contents

How was the Stone Scripture in the Japanese American National Museum discovered and acquired? After the defeat of Japan, detainees were freed and the Heart Mountain concentration camp lost is raison d’etre. Unattended and fallen into ruin, the cemetery and surrounding lots were divided and distributed as farmland.

The cemetery portion was given to a farming couple, Mr. and Mrs. Leslie and Nora Bovee. One day while working on the site, Mr. Bovee uncovered a mass of stones spilling out of a metal drum that had been broken open by his bulldozer. While the Bovees did not discard these mysterious small stones as useless, they did give them away few by few to relatives, friends, and visitors as curious souvenirs. As a result, when Mr. Bovee formally donated the stones to the Japanese American Museum in June 1994, the collection had been considerably reduced. The original total number is unknown, of course, but the total number of the current remainder is 656. Of course, 10 unreadable and 15 illegible due to ambiguity of simplified forms of character radicals (hen) or modifiers (tsukuri), thus leaving 631 readable stones.

We may now turn to the content of the Stone Scripture. In attempting to identify the text, we must take some preconditions into consideration. First, that since the copying was executed inside the concentration camp, the copied scriptures must have been in common daily use, probably brought by detainees into the camp. Because only Sino-Japanese characters (kanji) appear on the stones, we may exclude texts that are rendered in both kanji and kana (characters of the Japanese syllabary). If we consider texts used by the above named Buddhist sects, we can further narrow possibilities down to the three Pure Land Scriptures for the True Pure Land sects, the Heart Sutra and portions of the Lotus Sutra for Zen sects, the Hannya Rishukyo aand Heart Sutra for the Shingon sect, and the Lotus Sutra for the Nichiren sect.

Another limiting factor is the original total number of stones. We can roughly set the upper limit based on the size of the metal drum in which the stones were buried, along with the general size of the stones themselves. Given these conditions, we analyzed and examined the Stone Scripture text against the sectarian scriptures outlined above. To do this, we created a database of all characters represented on the stones and compared this data with the selected texts in the so-called electronic Tripitaka (a digitized version of the Buddhist scriptural canon). In executing this computer-assisted analysis, it was necessary to take into consideration not only the existence of a given character, but also the frequency of its appearance. This analytic work was undertaken by Professor Kenryo Minowa of the University of Tokyo, who came to the conclusion that the text in question is a group of selections from the Lotus Sutra. The first five or six books (out of eight total) matched best, when compared with the other sectarian daily scripture texts.

*This article was originally published in the Interreligious Insight, Vol. 9, Number 1, July 2011.

© 2011 World Congress of Faiths, Common Ground, and Interreligious Engagement Project