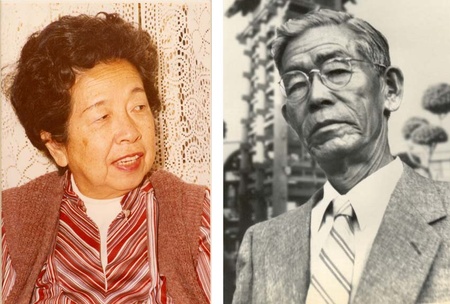

My father and mother, Kumezo and Nobue (Komuro) Hatchimonji (originally spelled Hachimonji) were, like so many other immigrants from Japan, two Issei individuals who came to America to start a new life, a new family, and to seek new opportunities. Like their fellow Issei, theirs was not an easy life but with characteristic patience and hope, they succeeded with a legacy of achievement and pride.

To describe some of the cultural traits that the Issei generation possessed, certain generalizations can be made, characterizations found in my parents. These characteristics are commonly thought of as perseverance (gaman) and an indomitable spirit to succeed; patience and resiliency of a shikata-ga-nai (“it cannot be helped so let’s move on”) attitude; and a strong work ethic. Adaptability could be added as they entered a strange and foreign land and faced people who did not always understand them. As a result, they endured widespread racial discrimination and other injustices.

My parents, however, were from a minority Christian background in Japan. Growing up, both attended American missionary schools where they learned to speak English fluently. In fact, they met in the United States and married as Christians. Mother’s father, our grandfather came to the U.S. as a Christian minister.

Prior to his marriage, my father was a student at New York City’s Columbia University, having his arrival in New York, he had a job as a fireman aboard a merchant ship delivering cargo to far-off international ports. As a young man of 17, from a poor farming family, he left Japan in search of adventure and a desire “to see the world.” The hard work of shoveling coal into the boilers of the ship as a fireman, however, ended when he decided to become a schoolboy, working for a wealthy family in New York while attending Columbia.

As often happened, our father’s college degree did not open doors of opportunity to him. After marriage, the family moved to El Centro, California, where our father became the secretary of the Japanese Association. In the fairly large Japanese community, his English language fluency was needed as an interpreter in matters such as land leases and other disputes and legal matters. It was in El Centro that my brother Mike and I were born as twins.

After several years, the family moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where we opened the Valley Seed Company. My father saw the possibilities in selling vegetable seeds to the large Japanese population, most of whom were vegetable farmers. Later, we moved to El Monte, California to re-open the seed company. Again, my father’s customers were the large number of Issei truck farmers in the Southern California area whom he called on as a traveling salesman. It was during these years that sister Gloria was born, thus rounding out the family.

El Monte was a city with a segregated school. All Asian and Latino children were placed in a sub-standard, dilapidated school called the Lexington School. Ironically, even though we lived next door to an all-white school, my brother and I could not attend there. Because my father saw the injustice of a segregated school for his children, he went to a neighboring school district and asked if his children could be allowed to attend the Mountain View School, an integrated school located some distance away. Thankfully, we were allowed to attend and spent most of our grammar school years there.

Then in 1941, the war with Japan broke out, and everything took a dramatic turn for the worse. The impact on the family was devastating. All was lost and the pain of the accusation of disloyalty ran very deep. Probably, besides our physical and economic losses, the loss of our place in the community where we had settled, saddened our parents deeply. When the orders for us to be removed and incarcerated were issued, the term, shikata-ga-nai, was heard.

At the Mountain View School, when the notices for our evacuation were posted in public areas, my brother and I were called into the principal’s office, something that caused fear in us. But, contrary to our worries, the principal told us that we were loyal Americans, that it was a mistake to take us away and that he was sorry to see us leave. He even gave us an American flag. Looking back on what he told us is a reminder that some people believed in us.

The camp experience, as adverse and uncommon as it was, cast the family into a new and strange life in an entirely foreign environment. After being forced from our home, the emotional stress of confinement and regimentation in a concentration camp was underserved and took a heavy toll on our parents. The stark desert landscape of northern Wyoming and the hastily-built barracks we were assigned to create a gulag-like Siberia setting, especially in the harshness of the winters.

But characteristically, our Issei parents had the resiliency and adaptability to survive and make the best of a difficult situation—gaman or perseverance would be an appropriate word here. Nevertheless, under such circumstances, there were cases of emotional breakdown and depression in the community and the disintegration of family.

But the camp experience could have its positive aspects. There were even moments of levity that, as we look back on them are amusing, but were not at that time. When we first arrived at Heart Mountain aboard an antiquated passenger train that took four days to travel from the assembly center at Pomona, California, to our destination, we were transported on the back of a flat-bed truck with other newly arrived internees to our unit in Block 27. It was already late in the evening when we opened the door to our austere barrack room and turned on the light. We were frightened by a large bat flying about the room. After managing to chase out the creature, we thought of the incident as a terrible omen of the future. It was a chilling introduction to our new life.

Another experience that was more serious for my teenage brother and me and others like us had to do with food. The meal serving times at all of the block mess halls were the same, much like it is on a military base. It usually lasted an hour. As hungry teenage boys, when individual servings at our mess hall were insufficient and no seconds were given, we would hurriedly rush through our meal and dash over to the neighboring block’s mess hall for another serving. Queues always formed at mealtimes, so waiting was time consuming. Trying to satisfy voracious appetites, sometimes as many as three meals within an hour was possible. In time, servings became more generous, and mess hall use was restricted to residents of their own blocks, so it wasn’t necessary to visit neighboring mess halls. Meals taken in the mess halls and not at home, where families sat together, had an adverse effect on family life and the authority of parents.

Rather than resign themselves to their uncertain futures, there were opportunities for all to work for the everyday operation of the camp. Many jobs with salaries were available in various activities. These were in everything from unskilled labor to the professional level. Ditches were dug by some; teachers taught at the schools; and nurses worked in the hospital. As a result, camp life improved as the internees “pulled themselves up by their bootstraps.”

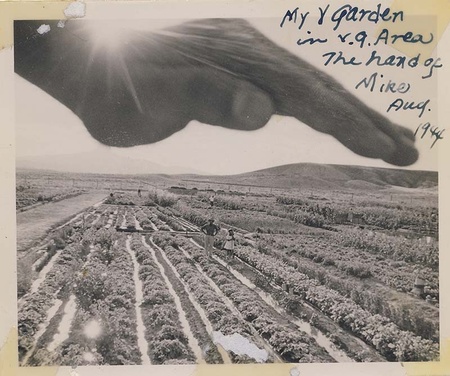

Our father became a block councilman, representing the 500 or so residents of Block 27. Sitting on the camp council and dealing directly with the administration, he was able to resolve issues and personal family problems and, in general, serve the community in a positive way. In addition, our father initiated and organized the Victory Garden program, a popular effort by Americans to augment the food supply during the war. Because of his background in vegetable seeds, especially Japanese varieties grown by truck famers, he was able to supervise the planting of crops favored by internees.

Popular vegetables seeds such as nappa, daikon, eggplant, and cucumber were brought in from the stocks my father had in storage on the West Coast. A simple irrigation system was installed on several acres of land outside the camp’s perimeter. Simple hand tools were supplied by the administration. After all of the inputs were in place, the project thrived. An abundant supply of fresh vegetables was shared by the over 10,000 residents of the camp. Not only was there an available supply of vegetables desired by the Japanese diet, but probably more importantly, it gave the participants, most of them farmers, a chance to do what they enjoyed doing best. And it was their contribution to the community. A government-assigned anthropologist, with whom our father spent many hours discussing the thinking of the internees, gave high praise to the Victory Garden program for what it accomplished.

With the end of the war and the transition back to the normalcy of mainstream American life, much could be said about that period which, for some, lasted for many years. For some it was a time of great trauma; while for others, like the young and independent, it was a welcome opportunity for change. The dynamics within families were altered dramatically. For some, the adjustments created serious problems. The families headed by Issei, with alien status, had many difficulties. With no homes to return to, no employment prospects and little or no financial resources, the challenges were enormous. Being suddenly thrust into the reality of a new life with little or no resources caused great stress. The government, knowing full well what awaited the internees, offered no assistance. Only $25.00 per internee and a bus ticket to their place of relocation was provided. Not only that, continuing anti-Japanese attitudes greeted many, especially on the West Coast. For example, in Imperial County, California, where some 2,500 Japanese previously lived, the County Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance during the war that prohibited the return of any Japanese families. They faced arrest if they did. As a result, even to this day, few have returned there. The ordinance was later rescinded.

Our parents faced similar problems, and the needs of the family were a heavy burden on them. Our father restarted his business in Arizona where some Japanese truck farmers could become a customer base. However, to obtain credit status with wholesale suppliers proved difficult. Without wholesale seed houses to supply him with seeds, there were times when he went into abandoned vegetable fields, salvaged what leftover produce there was, and processed the mostly decaying fruits and vegetables for usable seeds, which he then dried, cleaned, and sold as seed. It was a difficult process.

Despite these economic hard times, our parents sacrificed their own needs and worked diligently to provide food, a place to stay, and education for the three children. It truly was kodomo-no-tame-ni (for the sake of the children) in a very real way.

Some 12 years later, the Valley Seed Company was well-established in the Imperial Valley. Our father passed on in 1956, and I agreed to take over the business with our mother. We children had completed our educations, had begun our own professions, and began raising families of our own. Until their passing, our parents were always concerned about our economic security. In fact, regrettably, they never took a vacation. However, as they aged with their accompanying health problems, they were content with their family and what they had achieved.

Years later, in 1989, our mother passed on and with her death, the legacy of our parents’ lives will continue to remain in our memories. If we could exemplify two immigrants who came to this country many years ago to fulfill the American dream and did, it would be our parents. With so much against them from the time they entered this country, they never lost faith in their adopted country. Part of the dream was to become an American citizen. Only our mother was able to do that. Being denied that recognition for so many years was a great injustice to so many of the Issei.

The story of all our Issei forefathers follows a similar path. By and large, it was a saga of success. They all faced some of the harshest problems any immigrant generation could have faced. Most were courageous individuals who overcame great challenges, and their heritage is to be admired. No doubt, it was their cultural attributes that gave them the strength to forge ahead and made them, I believe, a unique group of immigrants. What they left behind is a valuable birth-right that we can all be proud of. I know that we can be enormously proud of ours.

* This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices: The Japanese American Family (Volume IV) in 2010. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2010 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California