On January 7, 1951, Moto Hayami held her newborn grandson in her arms and prophetically said, “Fred is going to be the lawyer of the Fujioka family.”*

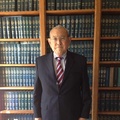

Indeed, Judge Fred J. Fujioka of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County has fulfilled his grandmother’s expectations in becoming not only the “lawyer of the Fujioka family,” but also the community organizer, the political activist, and last but not least, the judge of the Fujioka family.

A Long Line of Japanese American Legacies

Judge Fujioka hails from a long line of Japanese American legacies that he proudly showcases inside his chambers at the Sylmar Juvenile Courthouse in Sylmar, California. Nearly every square inch of his walls is covered by his extensive collection of family memorabilia.

To the left of Judge Fujioka’s desk hang pictures of his grandfather who arrived in Kansas City in the early 1900s as the first generation of Fujiokas in the United States.

“He was probably here to avoid the draft during the Russian Japanese War, and he couldn’t go back to Japan after that,” Fujioka said.

Ultimately ending up in Los Angeles, his grandfather found lucrative wealth in the automobile industry.

“He was real wealthy,” Fujioka explains. “He attended CalTech, invented a coal engine, [and] made a fortune. He started a company that was going to market a car in Japan and that had the whole manufacturing plant on the dock in Yokohama to be reassembled. When the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 hit, it was still sitting on the dock, it all went into the harbor, and he lost everything. So that’s the first fortune he lost. Then he came back here, and he had the largest Oldsmobile lot in Southern California. He sold trucks and cars and tractors to Japanese farmers, and that’s when he made his second fortune.”

Yet with the advent of the Pacific War and the increase in anti-Japanese sentiment, the Fujiokas lost everything once again.

“They picked him up within two hours after they bombed Pearl Harbor because the FBI had him under surveillance. He was a community leader; he was the head of the Hiroshima kenjinkai. The FBI arrested him and confiscated all of his property—so he lost everything when the war started,” Fujioka said.

Meanwhile, Judge Fujioka’s father, William Fujioka, enlisted in the army and served as one of the first members of the 442nd—the most decorated unit in the history of the United States, composed almost entirely of second-generation Japanese American soldiers.

“He was with them since the beginning, and he participated in all the battles including the rescue of the Lost Battalion,” Fujioka explained. “That picture is my dad on the far right, and the other two men are his cousins. The man he is standing by was killed a week after they took this picture on the last day of fighting in Europe.”

Though the wealth of his grandfather was never recovered after the war, Judge Fujioka asserted, “What I got that was more important than a nice house or money was a legacy. I didn’t really grow up with sports heroes or movie stars as heroes. I grew up surrounded by men who served in the 442—who I revere. So the greatest gift to me was I knew what heroes looked like—they looked like us. It’s huge.”

Forging His Own Legacy from a Young Age

Having inherited the stories of sacrifice and discrimination from the Fujiokas that came before him, Judge Fujioka always knew he wanted to be a lawyer.

“It was a fast track to being empowered,” he reasoned. “People couldn’t run me over if I am a lawyer, and I was right… Not just by litigating the law, but because I am a lawyer, I know the people who make the laws, I know people who interpret the laws, and because of that, the community is empowered as long as I use it for a common good and not just for myself.”

In fact, in as early as the fourth grade, Fujioka already had his sights set on law school.

“I just had it mapped out. I would go to West Point, do my active duty, go to law school on the GI Bill, and then become a lawyer,” Fujioka recalled.

However, after receiving his acceptance to West Point, he suffered a fateful blow to his knee in a wrestling match during his senior year of high school—thereby making him no longer eligible to enroll.

Despite the setback, he moved onto the University of Southern California (USC) where he graduated summa cum laude with a degree in Urban Studies.

Yet besides achieving a perfect GPA, Fujioka worked as a community organizer and outreach worker for the Casa Maravilla Foundation in East Los Angeles during his undergraduate years.

“I had to deal with the gangs directly,” Fujioka explained. “To get ‘street cred,’ I would get them into school, get their mothers benefits, get their kids into day care, and I would do all of those things so that I could ask them later to put their guns down and not to shoot people because they owed me—it was a trade off.”

Studying Abroad in Japan as a Japanese American

During his sophomore year at USC, Fujioka traveled across the Pacific and spent a year abroad studying at Waseda University in Japan.

Upon arrival, “It was real clear that I wasn’t Japanese, and I was okay with that,” Fujioka said.

In fact, the year he spent in Japan “more sharply defined the differences rather than similarities” between Japanese and his own Japanese American culture.

“The Japanese culture here, especially when I was growing up, it was totally different from Japanese culture in Japan,” Fujioka explained. “Basically, the Japanese immigrants came out of the Meiji Period, and then the United States cut off immigration in 1922 and so our culture—the culture I grew up with—was archaic. It would be like the equivalent of a whole group of people leaving the South at the end of the Civil War and then cutting off immigration for 50 years. They would think in weird terms that no one understands anymore.”

A piece of Japanese culture he did adopt while in Japan was aikido—a form of martial arts that he still practices to this day.

“I started aikido when I was there, and I was able to practice at the world headquarters. Eventually I was able to get my fourth-degree black belt,” Fujioka revealed.

Representing the People

Just as he had planned, Judge Fujioka graduated from Boalt Law School in 1977 and eventually served as a Deputy Public Defender for the Los Angeles County Public Defender’s Office.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would have been a prosecutor,” Fujioka confessed. “If I could go back in time and give my younger self advice, I would’ve said, ‘No, you could do a lot more to affect justice as a prosecutor.’”

“But I just couldn’t do it because a great injustice had been done to my family who had lost everything even though they had done nothing wrong. I couldn’t see myself representing the government. I’d rather represent the little guy—so that’s why I became a public defender,” Fujioka explained.

His choice of career as a public defender was also in large part due to the fact that there were only a select number of Japanese American lawyers who could offer career guidance to rising attorneys like Fujioka.

“I had no one to give me advice,” Fujioka expressed. “I didn’t know any lawyers except Bob Takasugi—he was a lawyer then. And when I got out of law school, he was the only judge I knew. There just weren’t that many Japanese American attorneys in our community.”

*Thank you to Linda Fujioka, Judge Fujioka’s mother, for sharing the introductory anecdote.

© 2014 Sakura Kato