The century-old document below is held in the archive of the present-day Wintersburg Presbyterian Church (the former Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission and Church). It is a compelling document, placing the Mission and Church site in the context of the historic struggle for civil liberties and the desire to become American. The Mission is the oldest Japanese church in Southern California.

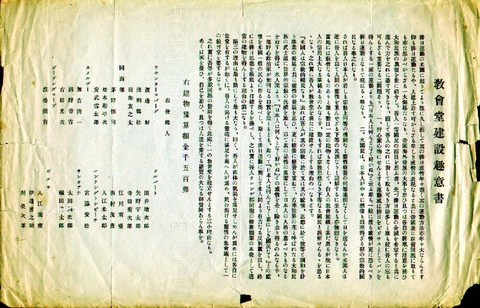

Click to enlarge: The "Prospectus for establishing a church" document, written circa 1902-1904, was graciously translated by a congregant of the Wintersburg Presbyterian Church and a scholar associated with the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, California. (Image, Courtesy of Historic Wintersburg and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church)

Faced with the need to raise funds for the first Mission building, Orange County’s Japanese community circulated the prospectus to explain the need for donations. The document first acknowledges the anti-Asian sentiment of early 1900s California and the fact that European Americans did not understand them, their culture or their spirituality.

“The growing intensity of the anti-Japanese movement which from an humanity’s perspective should be impermissible is also a serious insult directed against the Japanese. From Japan’s point of view, and that of the people who seek a future abroad, and those who want Japan to maintain its standing as a first rated nation, the complete elimination of an anti-Japanese movement is desired. Moreover, it is not just a matter of hoping that it will happen but working together to make it happen.”

In California’s Story, a 1922 textbook “written to meet the State requirement for the teaching of the history of California,” there is reference to the “Chinese question” and later, the “Japanese question,” both preceded by the “Indian question.” Its authors write, “there has been a steady growth of trade with the great nations of the Orient, like China and Japan. The prosperity and good order of all these places is very directly of importance to California, for she has much trade with them.”

California’s Story continues, “In the case of Japan there has been trouble at times because of the coming of more Japanese to California than our people like to have living here and owning property in the state. But up to the present, in spite of outcries and angry talk on both sides, the wiser people of the state have tried to smooth out difficulties in a just way.

In more ways than one, California and Japan need to be good friends, and this should be remembered whenever the ‘Japanese question’ is talked about.”

Gathering together in a barn in Wintersburg with the encouragement of Presbyterian clergy from nearby Westminster and Episcopalian minister Hisakichi Terasawa from San Francisco (see Voices from the Past Part Four, the Wintersburg Interviews, April 14, 2012), representatives from the broader Orange County Japanese community attached their name to the document and initiated a plan of action.

“Two important issues to consider to make this possible are: 1) There are people who are engaged in making the anti-Japanese movement a project, but the more worrisome issue is the growing feeling of people expressing a dislike of the Japanese even though there is no basis or particular reason for having this feeling; 2) Americans need to believe that the Japanese are religiously inclined, but if an organized endeavor or religious structure where their religion is practiced and developed is not visible, Americans will look down on the Japanese as a backward people who can live life without the necessity of a church where they can develop themselves.”

The Japanese recognized the symbolic nature of a church building in American culture. It would not only be a place for the Japanese immigrant community to gather and support each other, it would reassure European Americans that there was common ground, similar aspirations, and a desire to become part of the community.

“So even if we claim to have places of worship, without an actual structure (church), the Japanese, unlike Americans whose Caucasian social system is organized around a church, not having a church makes Americans distrustful of us and allows them to judge us a low class people to be looked down upon. That is the reason why we want to establish a church.”

The pain of not being understood and the desire to assimilate into American culture permeates the document.

“One reason regarding point number two that makes building a church necessary is that Americans are very religious people, so if we can understand how they think and feel about religion, we can promote harmonious relations and work together. And if we can develop our own spirituality, then Americans will probably accept us, and we will be able to slowly incorporate their way of thinking into our bushido spirit, and by doing so it will show our worth and value to Americans, changing their attitude and eventually the anti-Japanese movement will disappear.”

A significant cultural barrier was the lack of understanding by European Americans regarding the spiritual beliefs of the Japanese immigrants and of the concept of bushido. The use of the word is revealing in that many Japanese were emigrating because feudal Samurai ways were ending. In several of the oral histories of Wintersburg, there is mention of a family having Samurai roots.

Bushido, the Soul of Japan, penned by Inazo Nitobe in 1905, explains it is a “code of moral principals which the knights were required or instructed to observe,” much like the code of chivalry understood in feudal Europe in which religion played a significant role. Orange County’s Japanese knew bushido and Christianity were compatible.

“A second reason for building a church is that with a church and based on an understanding of Americans’ religious point of view and incorporating their ideas into our bushido spirit, we can work diligently to train ourselves to be in harmony with American Christian ways. This will change their ideas of why they dislike Japanese and they will find us attractive people. This is the reason why we Orange County comrades want a church.”

Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission, circa 1911. The original Mission building (above) is still intact at Warner (formerly Wintersburg) Avenue and Nichols Lane in Huntington Beach, next to the manse and hidden behind the 1934 church building on the corner. The actual Mission construction initiated in 1909--after years of fundraising--with the first service in December 1910. (Photo Courtesy of Historic Wintersburg and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church)

A final reason for the church-building effort expressed in the document testifies to their own simple need for a spiritual and community center.

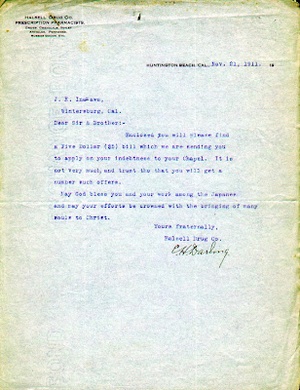

Click to enlarge: Donation letter from E.H. Darling, Nov. 21, 1911. The $1500 fundraising effort continued after the Mission was built, receiving a $5 contribution dated Nov. 21, 1911, from Huntington Beach's E.H. Darling, who also owned Darling's Pharmacy in nearby Garden Grove. E.H. Darling writes, "Enclosed you will please find a Five Dollar ($5) bill which we are sending you to apply on your indebtness to your Chapel. It is not very much and trust tho that you will get a number such offers." (Image Courtesy of Historic Wintersburg and Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church)

“It is a simple but a major third reason for building a church. Like people who are hungry who need a place that provides food, people who hunger for spiritual satisfaction need a place that provides it.”

The prospectus concludes with a call to action to the “many people who are concerned about Japan, or about our own situation, or what is right will participate in this endeavor.” Setting a goal of $1,500, what has been referred to as the “reasons to build a church” document was signed by representatives of the Japanese community from Wintersburg, West Wintersburg, Smeltzer, Garden Grove, Talbert, Huntington Beach, Santa Ana, and Bolsa.

Among the signatories was Tsurumatsu “T.M.” Asari, one of Wintersburg’s goldfish farmers, and Yasumatsu Miyawaki, reported in a Wintersburg oral history to have owned the first Japanese grocery store in Huntington Beach (likely the Talbert-Leatherman Building on Main Street, the present-day Longboard Restaurant and Pub).

The church-building effort was noticed by the European American community in Orange County, although the California Japanese community’s road to acceptance and civil liberties had yet to face its largest obstacle.

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on May 7, 2012.

© 2012 Mary Adams Urashima