Al principio de la mayoría de las organizaciones comunitarias, hay voluntarios. Si uno estudiara las entidades estadounidenses sin fines de lucro, ya sea que se dediquen a la historia, la cultura, los servicios sociales o la lucha contra las enfermedades, un tema común es que los grupos perdurables, grandes y pequeños, son impulsados y sostenidos por las incalculables contribuciones de sus voluntarios. . Los voluntarios aportan sus habilidades, experiencia, liderazgo, tiempo, dinero (y a menudo todo lo anterior) a una misión o causa especial.

Este folleto, ideado y patrocinado por Nitto Tire y traducido, escrito y publicado por The Rafu Shimpo , es una colección de perfiles de personas que son voluntarias o han sido voluntarias en el Museo Nacional Japonés Americano (JANM). JANM celebra su 30º aniversario desde su incorporación en 1985 y, como cualquier institución, la fundación, la cultura y el éxito del Museo se pueden entender mejor a través de sus voluntarios actuales y anteriores. La mayoría de estos individuos han observado humildemente que no son significativos ni notables. Pero JANM ha recurrido a muchos de ellos en busca del tipo de contribución más personal. Les ha pedido que compartan sus historias de vida.

La misión del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano es fomentar una mayor comprensión y aprecio por la diversidad étnica y cultural de Estados Unidos preservando y compartiendo la historia de los estadounidenses de ascendencia japonesa. Desde su incorporación, JANM se ha convertido en una institución reconocida internacionalmente que presenta exhibiciones innovadoras, programas públicos, documentales en video y planes de estudios, todos basados en la filosofía de que no hay reemplazo para los relatos en primera persona de las personas que vivieron esta historia.

Pero cuando se fundó JANM, muchas de esas historias no estaban registradas ni documentadas. En la década de 1980, la generación de inmigrantes Issei que llegó de Japón a principios del siglo XX había desaparecido casi por completo y se había llevado gran parte de su historia consigo. Además, la tumultuosa experiencia japonesa-estadounidense de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, que incluyó acusaciones falsas de deslealtad y el traslado forzoso ilegal y el encarcelamiento masivo de miles de personas por parte de su propio gobierno, siguió siendo en gran medida desconocida, incluso para los descendientes de las familias que la sufrieron.

Para comprender y apreciar mejor las contribuciones de los voluntarios de JANM, es esclarecedor revisar los orígenes de la institución. “Construir una institución desde cero requiere una participación práctica significativa”, observa Irene Hirano Inouye, directora ejecutiva inaugural, presidenta y directora ejecutiva de JANM. "Los voluntarios del Museo Nacional fueron y siguen siendo una fuerte razón para los muchos logros a lo largo de los años".

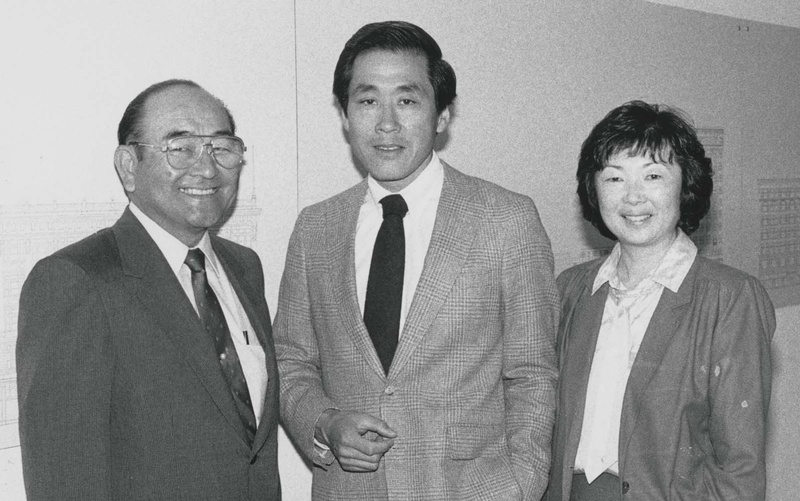

Nancy Araki, la primera miembro del personal de JANM, que luego se desempeñó como directora de relaciones comunitarias, explica que la fundación del Museo fue el resultado de la fusión de dos grupos, cada uno de los cuales buscaba crear un museo de historia japonés-estadounidense. Según Araki, en la era previa a la incorporación, el 100.º Batallón de Infantería/442.º Equipo de Combate del Regimiento/Fundación del Museo del Servicio de Inteligencia Militar, dirigido por el Coronel Young Oak Kim y Y. Buddy Mamiya, contrató a Visual Communications (el grupo de artes mediáticas dirigido a la vez de Araki y Linda Mabalot) para organizar dos exposiciones fotográficas sobre la historia de los veteranos japoneses-estadounidenses de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Mientras tanto, el veterano de MIS y presidente de Merit Savings and Loan, Bruce T. Kaji, y su Museo de Historia Japonés-Americano se habían concentrado más en desarrollar y construir un espacio físico para un museo en Little Tokyo.

"Llegué a conocer y trabajar con los voluntarios de Bruce, como el comité de arquitectura (que incluía siete arquitectos de cinco firmas diferentes) junto con un diseñador y un asociado administrativo de Merit Savings", revela Araki. “El grupo de veteranos se dedicaba a crear programas y el grupo de Bruce se centraba en el desarrollo de instalaciones. Pero ambos creían en la importancia de preservar y presentar la historia japonesa-estadounidense”.

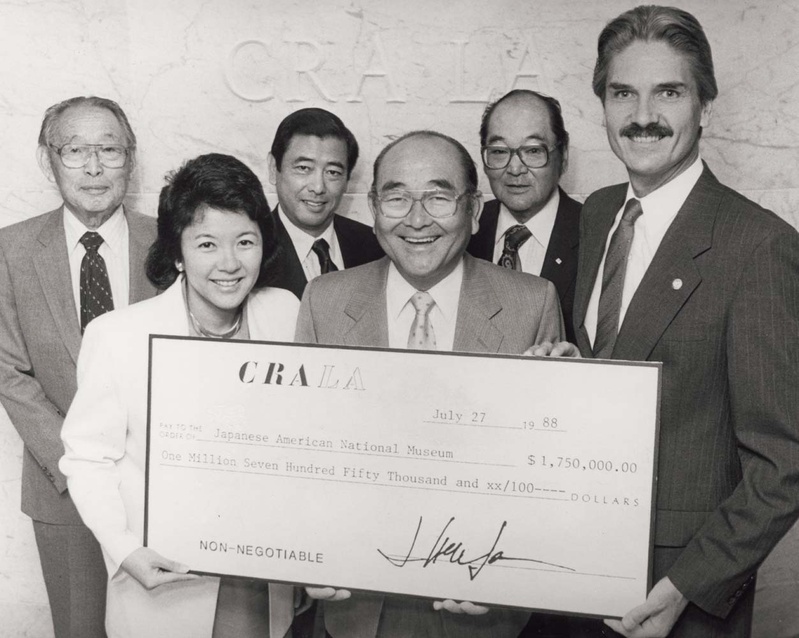

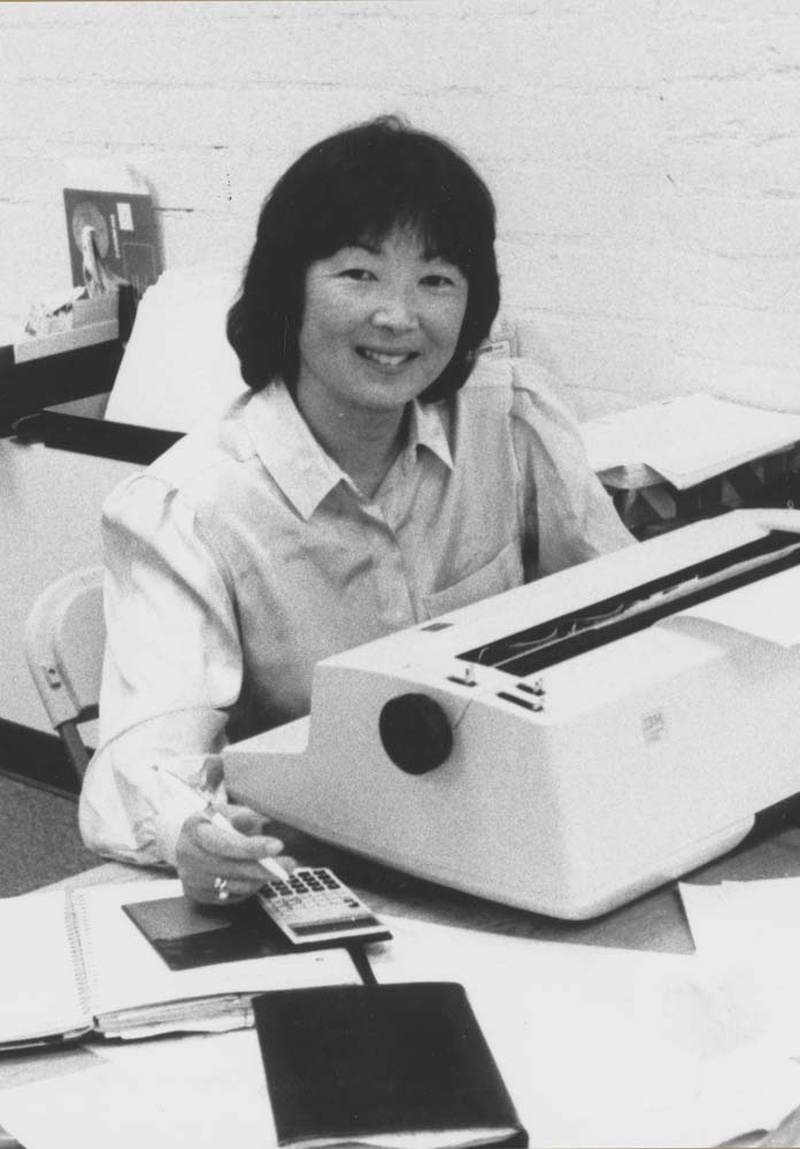

Después de la incorporación oficial en 1985 con Araki como único miembro del personal, JANM arrendó el antiguo edificio abandonado del templo budista Nishi Hongwanji de la ciudad de Los Ángeles gracias a los esfuerzos de H. Cooke Sunoo de la Agencia de Reurbanización Comunitaria y recibió una gran subvención de la Estado de California en 1986, gracias al Senador Estatal Art Torres. Después de instalar oficinas en un antiguo almacén en lo que ahora se llama el Distrito de las Artes, JANM comenzó a integrar a los primeros cientos de voluntarios como Masako Koga en su organización.

El primer curador de JANM, Akemi Kikumura Yano (quien sucedió a Hirano Inouye como director ejecutivo en 2008) se incorporó en 1987 para supervisar la naciente colección y preparar la exposición inaugural sobre los Issei. Con espacio y recursos limitados, Kikumura Yano organizó reuniones comunitarias que reunieron a académicos como Lane Hirabayashi, Yuji Ichioka y Robert Suzuki y figuras de la comunidad como Fred Hoshiyama, quienes contribuyeron con su experiencia y tiempo de forma gratuita.

Los voluntarios ayudaron a construir la colección. Por ejemplo, Hoshiyama relacionó a Kikumura Yano con el pintor Henry Sugimoto. "Hablé con Henry por teléfono (él vivía en la ciudad de Nueva York)", explica Akemi, "y me hizo una promesa verbal de donar al Museo sus pinturas relacionadas con la experiencia de los inmigrantes". Varias de las pinturas de la Colección Sugimoto aparecieron no solo en la exposición inaugural de JANM, Issei Pioneers: Hawai`i and the Mainland, 1885-1924 (1992), sino también más tarde en The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps. , 1942-1945 (1992), y exposiciones posteriores.

Hirano Inouye, quien fue contratado como director ejecutivo en 1988, recuerda haber trabajado directamente con un grupo de liderazgo voluntario que “permitió que el Museo desarrollara un fuerte alcance nacional e internacional. Los miembros de la junta directiva y los recaudadores de fondos como Noby Yamakoshi de Chicago, Siegfred 'Sig' Kagawa de Hawái, Francis Sogi de Nueva York y William 'Mo' Marumoto de Washington, DC pudieron conectar a JANM con líderes comunitarios y empresariales”. Gracias a Kagawa y George Aratani (fundador de Mikasa), JANM consiguió el apoyo de Akio Morita, presidente de Sony Corp. Esa relación llevó a una promesa de recaudación de fondos de casi 10 millones de dólares por parte de Keidanren (Federación Japonesa de Organizaciones Económicas), lo que permitió la construcción del Pabellón del Museo en 1999.

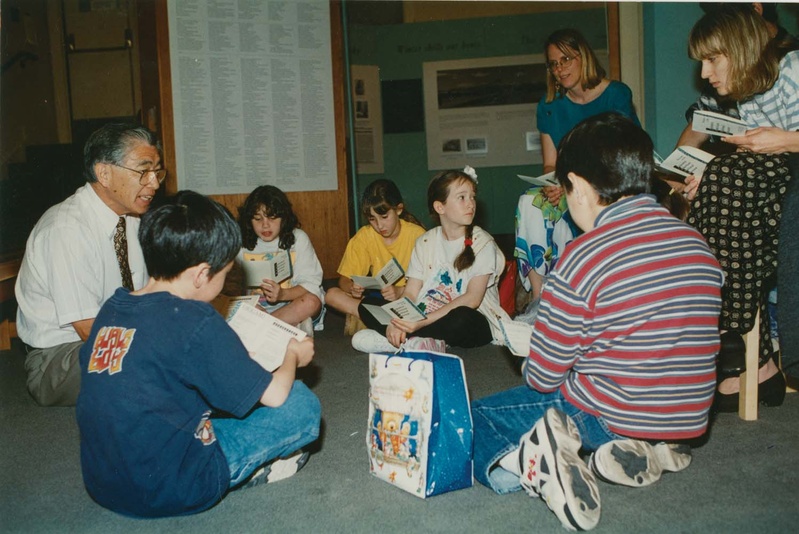

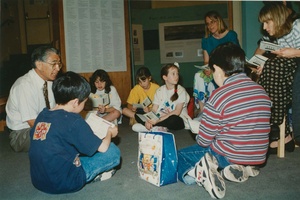

Cuando JANM abrió al público en 1992, el papel de los voluntarios se amplió. Hirano Inouye señala que los voluntarios “trabajaron en cada parte del Museo, incluidas las colecciones, las historias orales, las exposiciones, la tienda, la divulgación, la membresía y la recaudación de fondos. Cuando el Museo Nacional abrió las puertas del Edificio Histórico, los voluntarios actuaron como saludadores y docentes, lo que ayudó a que la experiencia del visitante fuera personal y acogedora”.

Los ex profesores Bill Shishima, Mas Matsumoto y Hal Keimi fueron clave para el establecimiento del programa de visitas escolares del JANM, “un sello distintivo del trabajo del Museo”. En apoyo a los miles de estudiantes que han sido guiados a través de JANM por docentes voluntarios, la recaudación de fondos “Bid for Education”, lanzada por otro voluntario, el fallecido senador estadounidense Daniel Inouye, ha proporcionado dinero para autobuses escolares, capacitación de docentes y admisión.

Tanto Kikumura Yano como Hirano Inouye elogian los esfuerzos de los voluntarios para recaudar fondos y crear exposiciones regionales para el Museo Nacional. Fred Hoshiyama y Florence Ochi, miembro del personal, organizaron a los voluntarios del sur de California para recaudar más de $1 millón a través de una serie de campañas.

Kikumura Yano dice que los voluntarios en regiones como Hawái, Oregón, Washington y Nueva York “contribuyeron con recursos financieros considerables. No sólo ayudaron a construir nuestra colección, sino que también participaron activamente en el registro, interpretación y autenticación de nuestra historia y cultura desde una perspectiva en primera persona”. Asimismo, Hirano Inouye reconoce las contribuciones de los voluntarios locales en la creación de exposiciones regionales como In This Great Land of Freedom: The Japanese Pioneers of Oregon y From Bento to Mixed Plate: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Multicultural Hawai`i . Los voluntarios regionales agregaron "diversidades importantes e historias no contadas a la historia japonés-estadounidense".

Es el hecho de que tantos voluntarios del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano hayan compartido sus historias personales lo que los hace únicos. Este folleto contiene perfiles bilingües de los voluntarios de JANM, que cuentan historias sobre sus familias y sus vidas personales. Si bien las entrevistas brindan información sobre las vidas de los voluntarios, no son historias orales llenas de detalles académicos, sino breves vistazos a las historias personales de un grupo notable de personas. La mayoría de las entrevistas fueron realizadas por The Japanese Daily Sun y todas fueron escritas, traducidas y editadas por The Rafu Shimpo .

La lista de voluntarios cuyas historias se incluyen en este folleto cubre la larga existencia del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano. Desde los primeros voluntarios como Masako Koga (ahora Murakami), Teri Tanimura y Bob Uragami hasta los más recientes y mucho más jóvenes Ryan Taketomo y Kyle Honma, esta muestra representa las diferentes épocas de JANM. Hay tres parejas casadas (los Murakami, los Yamashita y los Yasuda), un puñado de 90 años, dos no asiáticos (Nahan Gluck y Kathryn Madara), dos mejores amigas (Janet Maloney e Irene Nakagawa) y varios japoneses. voluntarios que hablan. Un individuo, Ken Hamamura, tiene la distinción de desempeñar funciones como miembro del personal, voluntario y miembro de la junta directiva.

Sus historias familiares abarcan toda la historia japonesa americana. No sorprende que muchos de los voluntarios hayan invertido su tiempo y esfuerzo en conocer y documentar sus propias historias familiares. Si bien suele haber un hilo conductor en muchas de las entrevistas, sus perfiles representan una notable diversidad geográfica, generacional y cultural. Algunas familias llegaron en el siglo XIX y otras en las últimas décadas. Varias personas nacieron en Estados Unidos, pero se educaron en Japón. Si bien los resúmenes no son largos, intentan capturar la esencia de las personalidades y sentimientos de los voluntarios individuales y su relación con su herencia Nikkei.

Hirano Inouye resume sus sentimientos sobre los voluntarios del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano comentando: “Su mayor contribución ha sido dar vida a la historia central japonesa americana, que es el corazón del trabajo del Museo. Al compartir sus historias, su experiencia y su tiempo, han hecho del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano una institución única y significativa”.

* Esta historia fue escrita por Chris Komai para Voices of the Volunteers: Building Blocks of the Japanese American National Museum , un libro presentado por Nitto Tire y publicado por The Rafu Shimpo. Todas las fotografías son cortesía del Museo Nacional Japonés Americano.

Presentado por

© 2015 The Rafu Shimpo