“Why was I, an American citizen, thrown in prison without cause, without due process? I had registered for the draft, as required of citizens of my age and sex in 1942; why were they questioning my loyalty now? How could they do that? … If they restored my status as a rightful citizen, let me go free, out of this prison, I would do anything required of me. Why should I answer the questions?”

Regarding the loyalty questionnaire, or registration, such were the thoughts of a bright young man forced to leave his life behind for insert-euphemism-here. No matter what the government insisted on calling them, to Hiroshi, the camps were prisons: “[t]here was barbed-wire fence with guard towers manned by MPs armed with rifles and machine guns directed toward us—the inmates.” If possible to imagine, however, there was something worse than the physical confinement. Hiroshi explained that the “invisible fence enclosing our spirit; this imprisonment of the spirit, the psychological effect … was the most ravaging part of the camp experience, leaving a scar that would remain with us for the rest of our lives.”

When camp officials inquired why Hiroshi and his family refused to register he replied, “I did not want to answer the questions while I was held in camp and treated as if I were a dangerous alien.”

After being told he had no choice but to answer Question Nos. 27 and 28, he answered “No” in protest to the grim situation in which his own government placed him and his family.

Camp life for these supposedly “disloyal” Americans, such as Hiroshi and his family, became increasingly tense, hostile, and dangerous. Hiroshi concisely sums up the setting thusly: strikes, riots, martial law, tanks, tear gas, arrests, stockade, prison within a prison, threats, and violence.

Years later, Hiroshi “was devastated to read in Michi Weglyn’s classic Years of Infamy that the [loyalty] registration order had not been compulsory; there was nothing compelling [them] to register other than [the] threats, a fact the administration never disclosed to us. To this day, many believe the order was compulsory.”

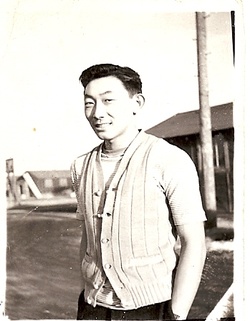

Hiroshi Kashiwagi grew up in California in a working class family where he helped his father in the fields. He grew up without many of the amenities that the youth of today take for granted. What does, however, bring a smile to Hiroshi’s face when thinking about his childhood is his mother’s togan soup. Togan was a greenish gray melon that grew plentifully in their garden. It was his comfort food. Thoughts of that soup remind Hiroshi of how resourcefully his mother accomplished so much with so little. He has continued to make his mother’s soup, and would eat it every day, in fact, if his wife allowed it!

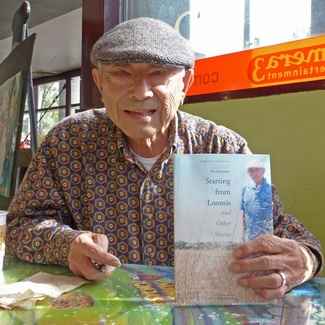

In his short story entitled Starting from Loomis, Hiroshi discusses his mother’s soup and many other aspects of his childhood in greater detail.

After Japan’s attack of Pearl Harbor and the signing of Executive Order 9066 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, he suffered through Arboga temporary prison and Tule Lake concentration camp.

The barracks at Arboga were “hastily built on what had been a pasture—swampland—which had been leveled by a bulldozer. The mosquitoes and gnats were vicious, especially with the women, feeding on their exposed arms and legs.” As Hiroshi recounts, “Our quarters in the tarpapered barrack consisted of a single room with four US Army cots, mattresses, and blankets. The partitions on both side of the room did not go to the top, so we could hear everything going on in the rest of the barrack.”

Tule Lake did not alter the low quality of living. It speaks volumes, unfortunately, that Hiroshi and others were excited about the nicer toilets at Tule Lake: “After the miserable experience in Arboga, we were excited about the flush toilets in the latrines; in fact, we made a special trip to the latrine to check them out—two rows of porcelain toilets that actually flushed.” Of course the latrines still lacked partitions.

While Hiroshi does not apologize or regret his decision to answer “No” to those fateful questions in the loyalty questionnaire, he does delve into a vulnerability for which readers need to approach and appreciate with sensitivity. Sharing such a humbling experience with a wide audience is admirable and should not be taken lightly.

In his own words, Hiroshi describes renouncing his American citizenship while at Tule Lake “the dumbest thing I ever did in my life.” In Starting from Loomis and Other Stories, he takes readers through this traumatic period in his life. Reading a firsthand Japanese American account of renunciation during WWII is rare, and is no doubt best experienced through the author’s own words, so readers are encouraged to do just that. Sufficient for this article is the knowledge that the US government did admit wrongdoing and restored citizenship to Hiroshi and similarly-situated individuals.

After the war, Hiroshi felt alienated from the Japanese community because of his label as a No-No Boy so, for a while, he avoided other Japanese as much as possible.

With that said, however, it is vital to keep in mind that an individual should not be limited or defined by a tragic experience, even one as singularly appalling as what happened to Japanese Americans during WWII.

Sometimes we get so accustomed to reading about individuals within the context of the WWII camps that we only see their existence through that lens. To help us open our eyes beyond this narrow lens, this work is refreshing because it reminds us that these were hardworking people that did not let their horrible WWII experience deter them from having exceptional and impactful lives afterward.

See, Starting from Loomis… is definitely a capsule into Hiroshi’s life; but concurrently, it is symbolic of the life of any given person that suffered through the WWII camps. It is precisely through Hiroshi’s example that we can tangibly envision the triumph of all those who were forced into the camps—the reality that a triumph defined by a lifetime comprised of fulfilling experiences can diminish a single tragic event like the camps into merely a footnote in one’s life, albeit a rather large one.

With Hiroshi, he refused to allow his life to be defined by what the US government wrongfully carried out against its own citizens (or against non-citizen Japanese, for that matter). Hiroshi was not limited by the label of a No-No Boy. Starting from Loomis… stands as a testament that Hiroshi led and continues to live a spirited life. He did not live in the shadows. Quite literally, he did the opposite…he lived his life out in front of audiences, on stage.

Nihongo gakko is where Hiroshi picked up the acting bug. Later on, as Hiroshi puts it, “Strangely, camp gave me a chance to pursue what interested me the most: writing and acting, performing in front of people.”

At Tule Lake, Hiroshi was an integral member of the theater group. In Starting from Loomis…, he does a great job chronicling his growth and experiences performing in camp. Unfortunately, the theater group “came to an abrupt end with the institution of the loyalty registration order…when politics displaced art, when division, distrust, even enmity among the members—all caused by the infamous order—effectively killed off any creative energy within the group.”

After leaving Tule Lake, Hiroshi was a founding member of the Nisei Experimental Group, the first postwar Japanese American theater group, with which Hiroshi wrote his first play, Plums Can Wait. It turned out to be the group’s first production.

When he went to graduate school at UC Berkeley, Hiroshi continued with his passion for theater by writing plays like Laughter and False Teeth, and performing in such plays as The Tempest, The Duchess of Malfi, and Nativity Cycle. For his activities in the theater department, he was elected to the Mask and Dagger Society.

After graduate school, theater arts necessarily became a part-time activity for Hiroshi because he had to support his family with a more steady means of employment (city librarian). Still, make no mistake, he definitely managed to continue making his mark as a pioneer Japanese American writer, playwright, and actor.

Hiroshi appeared in several plays at the Asian American Theater Company; in a few TV commercials and “industrials” (e.g., employee training videos); and in the films Black Rain, Dark Circle, and Hito Hata—Raise the Banner, the first Asian American feature film. Hiroshi is particularly fond of his work in award-winning filmmaker Emiko Omori’s Hot Summer Winds and Rabbit in the Moon as well as his work with Tim Yamamura in The Virtues of Corned Beef Hash, an independent film by Kerwin Berk. He is also starring in Berk’s feature film Infinity and Chashu Ramen.

Hiroshi also found success as a playwright with the Center Players, which has performed at spaces such as the Japanese American National Museum, the Orange County Buddhist Church, and the Torrance Cultural Arts Center.

Beyond his impact in theater and film, Hiroshi’s book provides glimpses of a more complete picture of Hiroshi the person. He describes his affinity for dango, bento, and barracuda. He explains why Sacramento Nihonmachi has a special place in his heart. Furthermore, he enlightens us as to why his father’s hat represents who his father truly was, more than any other possession. While reading about the hat’s significance toward the end of Part I of Starting from Loomis… do not forget to peruse the included priceless family photos; it really helps visualize the events that occur.

Additionally, in the book Hiroshi adeptly incorporates many of his thoughts and reflections as he has come to acknowledge and even embrace his Tule Lake past, through his Committee membership, etc. He also reflects more generally what it means to be a Nisei, as well as more personally the circumstances surrounding his father’s disease and funeral.

So what can our community’s youth learn from Hiroshi’s life perspective? Hiroshi suggests, “Do not give up your dreams; if you want to do something bad enough, you will do it. Stick to your principles; do not be afraid to be different.” He adds, “Henry James, the famous writer, advised his young nephew, ‘Be kind, be kind, and be kind.’”

In some ways, yes, this work may be similar to others where Japanese Americans have shared their painful stories of incarceration in camps during WWII. But Hiroshi’s narrative is unique because there are very few memoirs—much less recorded testimonies—to capture the experiences of No-No Boys who have had to carry the misconception of a ‘disloyal’ American long after the war. If it is not clear from reading this article, it will be abundantly so after reading this book, that Hiroshi Kashiwagi passed such a test with flying colors…and then some.

Hiroshi is honored to have Starting from Loomis and Other Stories selected as part of the George and Sakae Aratani Nikkei in the Americas Series, and to be published by such a prestigious academic press as the University Press of Colorado. He is grateful to Professor Lane Hirabayashi, the Series editor, for its inclusion. Also Hiroshi appreciates his extraordinary editor Tim Yamamura for his assistance. Lastly, he would be remiss if he did not express how thankful he will always be to attorney Wayne M. Collins who spent a good part of his life on Hiroshi’s and others' behalf to restore their citizenship and correct the injustices they suffered.

* * * * *

Please join us on Saturday, January 18, 2014, at 2 PM, as the Japanese American National Museum hosts the American Book Award-winning author Hiroshi Kashiwagi for a book discussion regarding his work, Starting from Loomis and Other Stories. More infomation about this program >>

If you are unable to make this book event, it is available for purchase in the Museum Store or online at http://janmstore.com/151445.html.

© 2014 Japanese American National Museum