Daddy: Check the box that says “Caucasian.”

Me: Really? I didn’t know because I’m not completely Caucasian.

What about mom?

Daddy: The child’s race is determined by the father’s side.

That conversation between my father and me took place when I was around eight or nine years old. It was the first time I filled out official school paperwork on my own. It was also the first time I gave any thought to my race—both of my races.

The paperwork was easy at first. Name, address, phone number, date of birth—no issues. Then came the question about ethnicity. It was the late 1970s, so you can imagine the options. Caucasian, Black (not “African American”), Hispanic, American Indian (not “Native American”), Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The instructions said to check only one box, but I needed two. My father was a Caucasian American of Scottish descent. My mother is from Okinawa, Japan. One box was not enough.

So I listened to my dad—I always listened to my dad—and checked the box that said “Caucasian.” And I continued to check that box for the next twenty years, until a friend helped me realize that box was wrong because it didn’t allow me to be the whole person I truly was. That box forced me to be half. Technically, though, I am Hafu.

The word Hafu is the term the Japanese use to describe someone who is biracial, specifically, ethnically half Japanese. Whether the term is derogatory is debatable, but the Japanese see it as cut and dried: a Hafu is half Japanese and half something else.

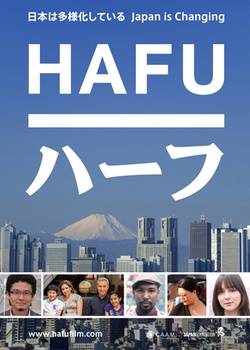

The memories of checking that Caucasian box came flooding back to me when I saw the documentary film Hafu: The Mixed-Race Experience in Japan, which made its New York premiere on Sunday, July 28 as part of the Asian American International Film Festival. The film shows that Hafu is more than a simple word. It is an identity—and oftentimes an identity crisis—that manifests itself at an early age.

Filmmakers Megumi Nishikura and Lara Perez Takagi, who are both Hafu themselves, explore the complexities of living in Japan when you’re only half Japanese. The time I lived in Okinawa was limited to 18 months when I was a baby, but I still felt a personal connection to Hafu. It was easy to tell that the near-capacity crowd in the Courthouse Theater of Anthology Film Archives felt the same way.

Nishikura and Takagi introduce us to four individuals and one family as they navigate the bumpy road that Japan has constructed for all Hafus. Japan would like to hold on to the notion that it is a homogenous country, but as the documentary shows, that is no longer the case. (My parents married in Okinawa in 1965, when Japan’s international marriages numbered at 4,156, according to the filmmakers, so we Hafus have been around for a while.)

Sophia (Australian mother, Japanese father), David (Ghanaian mother, Japanese father), Edward (Japanese mother, Venezuelan father), Fusae (Japanese mother, Zainichi Korean father), and the Oi family (Mexican wife, Japanese husband, two children) open our eyes to what it means to be of mixed race in Japan. Although the featured Hafus come from different backgrounds, they share similar anxieties, even young Alex Oi.

Bullied by his classmates in Japanese school, Alex asks to live with his mother’s family in Mexico because he “needed to understand himself better.” It’s heartbreaking that a nine-year-old would say that, but that’s part of the territory of being a Hafu in Japan. After spending several months in Mexico, Alex returns with renewed energy and transfers to an international school in Nagoya, where he makes friends and no longer suffers from stress.

Also bullied throughout his childhood is David, who spent ten years in a Japanese orphanage after his parents divorced. David inherited the physical traits of his mother, but he always identified more strongly with his Japanese heritage, even though he constantly has to explain his ethnic background.

“It must be hard introducing yourself a thousand times a year,” a friend said to David, but he relishes the opportunity to share his biracial makeup, saying it will help the next generation of Hafus to be accepted more readily.

David acknowledges that since he grew up in Japan, his mother’s native Ghana was an afterthought. After an acquaintance expressed his surprise that David was from two cultures but appreciated only one, David traveled to Ghana to learn more.

I identify with David in that respect. After checking the Caucasian box, I was just another white girl in a small town in North Carolina. I thought it was cool that my mom was from another country, though. I loved looking at old pictures of my mom’s family wearing kimono and seeing the “crazy” writing on my aunt’s letters. That was the extent of it. After returning to the States from Okinawa in 1971, our family never went back. My mom became an American citizen and spoke only English to my older sister and me.

Like David, I began to regret that I’d missed out on half of my heritage. I took my first Japanese lesson at age 30. My husband and I took my mom to visit her family in 2001, the first time she’d been home in 30 years. I travel to Japan once a year now and keep in contact with my Okinawan family. My life is much richer for it.

After reconnecting with his African roots, David established Enije, a non-profit that is building schools in Ghana. Throughout Hafu we see David at fundraisers and talking to potential donors in Tokyo and interacting with the children at his school in Ghana. By embracing both of his cultures, David is making a difference.

Another person from Hafu who is making a difference is Edward, who began the group Mixed Roots in Kobe to bring together other Hafus for social and educational programs. Raised in Japan by his Japanese mother and grandmother, Edward had a Venezuelan passport and needed to renew his Visa each year. The fact that the Japanese government required Edward to do this even though his family is Japanese, he is fluent in Japanese, he is Japanese, was bewildering to him. As a result, he never felt a part of his community when he was a child.

“I realized how important a community is,” says Edward, “so that’s when I started one of my own.”

Mixed Roots gives Edward a sense of purpose as he connects people in Kobe who have similar stories. He even met his wife through the group.

Mixed Roots reminds me of Japanese Americans and Japanese in America (JAJA), a community group to which I belong. JAJA aims to connect New Yorkers of Japanese decent (100%, Hafu, etc.) through monthly meetings that focus on our culture and the innumerable Japanese-related events in the city. The networking and community building of JAJA have been invaluable to me.

Mixed Roots became invaluable to Fusae because of her longing to share her secret that she is half Korean. Japan and Korea have a difficult history, which places a burden on children born of mixed Japanese and Korean heritage. Fusae didn’t find out her father was ethnic Korean until she was 15 years old because her mother was worried Fusae would endure bullying and discrimination.

Fusae was afraid to tell any of her friends this discovery, and she wore her secret like an albatross around her neck. Eventually, Fusae realized that acknowledging her Korean culture would be freeing.

“I wanted a place where I didn’t have to hide it,” she says.

She found that place with Mixed Roots, where she organizes activities for mixed-race children.

Unlike the other Hafus in the film, Sophia grew up in Australia and didn’t speak Japanese as a child. She arrives in Japan to live and work there, taking Japanese lessons and immersing herself in her father’s native culture. Her original goal of finding Japanese friends to help her practice the language doesn’t quite come to pass. She finds an Australian boyfriend and forms friendships with Westerners, saying that her Japanese friends spoke to her in English. After just over a year, Sophia returns to Australia, citing vague family reasons.

Of the Hafus in the documentary, I identified most strongly with Sophia. She didn’t grow up in Japan, doesn’t speak the language fluently, and doesn’t look Japanese. When she tells people that she’s Hafu, she hears exactly what I hear: “Oh, you don’t look it.”

Everyone I meet, regardless of race, asks me why I’m interested in Japanese culture and why I began this website (japanculture-nyc.com). Like David, I have to explain myself “a thousand times a year.” However, David’s attitude is inspiring me to be less sensitive to those questions.

Still, I share Sophia’s frustration when she remarks, “Even though you’re half Japanese, you’re not really Japanese.”

At the core, the featured Hafus simply want to feel part of a community and to be accepted. Being Hafu is a struggle, both within oneself and within society. It goes beyond checking a box that somehow defines you. Fusae’s advice to Japan is essential for any country or any individual: “Instead of disliking what’s different, embracing it and learning from it makes life that much richer.”

At the screening, my fellow viewers spent the entire 87 minutes of Hafu nodding their heads, finding connections with everyone who appears in the documentary. Hafu makes us open our eyes to the people we are, regardless of ethnic background, regardless of what box we checked in the third grade.

* This article was originally published on JapanCulture•NYC.com on July 27, 2013.

© 2013 Susan Hamaker