Read Part 1 >>

3. Internee or Incarceree: Say What You Mean

In the 1960s and 1970s, an attempt was made to move away from the government’s WWII era euphemisms of “evacuation” and “relocation”, which resulted in widespread use of the terms “internment” and “internment camp” in their place. Most people at that time were not aware of the Department of Justice camps and the specific legal definition of internment and internee. Current scholarship on the topic shows the widespread use of “internment” and “internee” to be inaccurate and therefore misleading when used in a general way to describe the WWII experience of Japanese Americans.

Internee—A specific legal term for a citizen of a foreign nation at war with the United States, detained or imprisoned by the DOJ during WWII. As such, this term would not apply to Nisei (US citizen by birth), nor would it apply to any Issei held by the WRA rather than the DOJ. By this legal definition, only Issei in DOJ internment camps can accurately be called internees. This is NOT an appropriate term to use in describing the ten WRA camps or those held there—it is inaccurate in the legal sense of the term and it feeds into the false stereotype that all Asians are foreigners.

Incarceree or Detainee—A general term applicable to any JA detained, imprisoned or otherwise locked up by the government, whether citizen or non-citizen, during WWII. A preferred and more accurate term to use for those held in WRA camps.

4. Segregation: Lives in the Balance

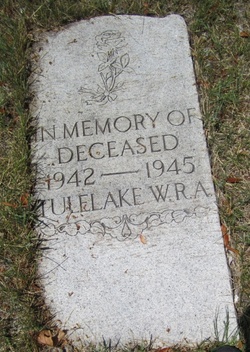

Grave marker at the Linkville Cemetery in Klamath Falls, OR. Ten stillborn infants and one man with no family were re-buried here after the camp closed in 1946.

Roughly one year after the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, the government decided to assess the loyalty of JA individuals by administering a lengthy “loyalty questionnaire” to all adults, which caused great confusion and anger within the WRA camps. Based solely on responses to two poorly written yes-no questions and administered to JAs one year after being stripped of all constitutional rights, it proved a woefully inadequate and arbitrary means of determining loyalty. It also created divisions and animosity within the community that persist to this day.

Disloyals—A WRA or government term applied to those providing unsatisfactory answers to the “loyalty questionnaire”. Anything other than an unconditional “Yes-yes” could result in being sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, e.g. no-no, yes-no, no-yes, yes but (i.e. a conditional answer), blank (i.e. no answer). This is an inaccurate and pejorative term.

No-No’s—A colloquial term for those the WRA judged as giving unacceptable answers to the loyalty questionnaire and therefore sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center. To this day, the label carries a stigma within the Japanese American community.

Resisters—Those who showed their resistance to the WRA and the “loyalty questionnaire” by refusing to answer or refusing to give the approved answer of yes-yes. This is the preferred term of the Tule Lake Committee as it affirms the desire of many JAs to protest their treatment by the government.

Segregants—A more neutral term for Nikkei segregated out from the general population and sent to Tule Lake Segregation Center.

5. Selective Service (the Draft) and Loyalty Questionnaire: Just Say NO!

There were few ways that Japanese Americans could officially demonstrate their resistance to unjust incarceration once they were in the camps. One was to defy Selective Service laws, i.e. the draft, and another was to answer “no” to the Loyalty Questionnaire. Both carried a heavy cost: federal prison or transfer to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in the short term, followed by severe social stigma and ostracizing within the JA community in the long term. The two groups are often conflated or mistaken one for the other, but they are not the same.

Draft Resisters / Objectors of Conscience—Those who refused to register for the draft once it was mandated for Japanese Americans, i.e. those who said “no” to the draft. About three hundred young men resisted in this way, the most organized group being the Heart Mountain Boys. Generally, their refusal was conditional on restoration of their civil rights and/or release of their families from unjust confinement in a concentration camp. Those convicted of draft evasion were sentenced to federal prison for terms of one to five years. Post-war, all were eventually granted a presidential pardon. This group resisted the draft.

No-No’s—Those who answered “no-no” to the “loyalty questionnaire” (or any other way deemed unfavorable by the government) and were then sent to Tule Lake Segregation Center. Over 12,000 men, women and children were labeled disloyal by the WRA and sent to Tule Lake. Some of these segregants also resisted the draft, but the two groups are NOT the same. This group resisted the “loyalty questionnaire”.

6. Renunciant and Deportee: Stay or Go?

Renunciant—A Japanese American citizen (Nisei) who renounced (gave up) his or her US citizenship. The vast majority of the nearly 6,000 renunciants were incarcerated at the Tule Lake Segregation Center. Not all renunciants were removed to Japan, and most were able to eventually restore their citizenship—though it took up to 20 years of protracted legal struggle to do so. Attorney Wayne Collins was instrumental in getting renunciants’ citizenship rights restored and preventing many from being deported against their will.

Denaturalization—On July 1, 1944, President Roosevelt signed the Denaturalization Act, which allowed US citizens to lose their citizenship by renouncing it in writing. This led to a program at Tule Lake Segregation Center near the end of WWII to allow, convince, cajole, or coerce Nisei inmates to renounce their US citizenship with a goal of then deporting them to Japan after the war (the government cannot legally deport a US citizen to another country).

Native-born alien—The government term for Nisei (native-born Americans and therefore US citizens by birthright) after they renounced their citizenship. This is yet another example of the government avoiding reference to their treatment of US citizens.

Deportee—A Japanese American who was deported to Japan after the end of WWII. This would be either an Issei “alien ineligible for citizenship” (i.e. Japanese citizen) or a Nisei renunciant (US citizen who renounced citizenship). US citizens can be extradited if accused or convicted of a crime in another country, but citizens cannot be deported to another country without cause or due process. In order to easily deport a US citizen, he/she must first renounce their citizenship. An exception to this might be the citizen minor child of a deportee who could be deported with his/her parent.

7. Tule Lake: Three Takes

Camp Tulelake—A separate facility about ten miles from Tule Lake Segregation Center that was built before the war as a CCC Camp. It was used initially as a temporary jail when trouble broke out at the Tule Lake Segregation Center and mass arrests were made. Some JAs were sent here to further segregate/isolate them from other inmates. Later, when the Tule Lake inmates went out on strike, it housed strikebreakers from other camps, and then it became a labor camp for German and Italian POWs sent to work on local farms. It is reported that the POWs at Camp Tulelake had more freedom of movement and local acceptance than the US citizen inmates at Tule Lake Segregation Center.

Tule Lake Relocation Center—One of the ten large concentration camps set up by the WRA to house the vast majority of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. It was built to house around 12,000 inmates, who were taken primarily from the Sacramento Delta region of California, most of Oregon, and the rural areas of western Washington.

Tule Lake Segregation Center—The renamed and enlarged incarceration center became the only maximum-security concentration camp where JAs the WRA labeled as “disloyal” were sent from all ten camps. Others whom the WRA considered as “troublemakers” were also sent here to segregate and isolate them from the general population. In total, about 12,000 incarcerees were transferred into Tule Lake from other camps. To make room for them, about 6,000 original Tuleans were sent to other camps or released on leave, and an entire new section was added to the original camp, expanding its capacity to over 18,000 inmates.

8. Jail and Stockade: A Jail Within a Jail Within a Jail

Over 18,000 people at Tule Lake Segregation Center were already imprisoned within a one-square-mile camp encircled by barbed wire fences and armed guards in watchtowers, but they could also be seized and arrested by security forces and thrown into the acre-size Stockade compound or locked inside a few square-yard Jail cell.

Jail—The concrete structure at Tule Lake with cells and bunks. It was built to house 24 prisoners, but at times it held up to 100 men.

Stockade—The fenced-in, enclosed yard surrounding the jail where up to 400 men were kept at one point.

9. International Injustice: Rendition in Reverse

Latin American Japanese—During WWII, over 2,200 people of Japanese descent were taken from their homes in Latin America (Peru primarily) and brought to the US without hearings or court orders. They were victims of an early form of what is now euphemistically called “extraordinary rendition,” i.e. the government sanctioned transport of people across international borders with no legal proceedings (e.g. warrants, hearings, indictments, or trials) and no legal papers (e.g. passports and visas) in an extrajudicial process (i.e. occurring outside the law; not governed by law). In essence, “extraordinary rendition” is government-sponsored kidnapping. There are some disturbing parallels to the current detention program at Guantanamo Bay.

Castle Rock provides a fitting backdrop for the Memorial Service held at the site of the cemetery for Tule Lake Segregation Center. All the remains were removed after the war: many families took their loved ones home for re-burial but a few were left behind and moved to the Linkville Cemetery in nearby Klamath Falls, OR.

* * * * *

Acknowledgements:

This paper is based on a PowerPoint presentation prepared for a workshop on The Power of Words: Coming to Terms with American Concentration Camps and the Japanese American WWII Experience at the Association of Asian American Studies National Conference held in Seattle, WA in April 2013. Many thanks to those who inspired, informed, and helped shape my thoughts on the subject, including: Professor Roger Daniels, Professor Tetsuden Kashima, Mako Nakagawa, Barbara Takei, Seattle JACL Power of Words Committee, and Tule Lake Committee.

© 2013 Stanley N. Shikuma