The summer of ‘63. Fundamental political and social changes swept across our nation. Civil rights battles overflowed into the streets. Confrontations and killings sparked racial unrest. A Baptist church was bombed in Alabama, killing four young girls. At the March on Washington rally, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I have a dream” speech. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled school-sponsored prayer in public schools was unconstitutional. The Viet Cong claimed their first battle victory over South Vietnamese and American forces.

And the top musical hit that summer was sung in a foreign language. Not in Spanish. Richie Valens’ “La Bamba” was released in 1958 but never reached the top spot. (In ‘58, another foreign language song—in Italian—called “Volare” did reach No. 1.) Not in French. Later in ‘63, the singing nun and her “Dominique” shot to the top of the charts.

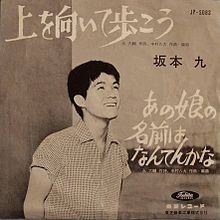

The musical hit of the summer of ‘63 was sung in Japanese. “Sukiyaki” reigned No. 1 for three weeks.

I remember first hearing Japanese on the radio when my non-English speaking grandmother listened to a weekly Sunday morning local show with news and music. But most of the time, our radio was tuned to KYNO, the local pop music station aimed at a teenage audience. We listened to it all day during the summer, in our fruit packing shed and in the fields on transistor radios.

Initially, I was shocked to hear a Japanese song echoing in our shed. Japanese on a rock ‘n’ roll station. Japanese that I could be proud of and not embarrassed by. A nation of young people seemed to like the beat, enjoy the rhythm, and accept the words. My school buddies badly mimicked the lyrics. I sang with a poor Japanese accent, faking most of the words. An import from Japan had penetrated the American landscape and rose to the top spot.

For Japanese Americans, “Sukiyaki” symbolized a type of acceptance. Only 20 years prior, my parents and grandparents had been interned in relocation camps. Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, they were deemed the enemy based on their appearance. For four years, 110,000 Japanese Americans, many American citizens by birth, were sent to prisons in desolate areas of the United States. Our family called the Arizona desert home, living behind barbed wire in barracks.

I was born after this tragedy and heard very little about it from my family and community. They internalized the pain and suffering, the shame and disgrace of false imprisonment, and the abandonment by country. Yet they returned to their American homelands and remained silent and stoic as they worked their way back. We spoke little Japanese at home.

Then came “Sukiyaki,” a song in Japanese about lost love and looking to the future. A repeated line, “I look up when I walk so the tears won’t fall” seemed to capture the Japanese American ethos. To look beyond the past, accept the sorrow and move on.

Of course, few of us Sansei (third generation Japanese American) and most of America didn’t understand the Japanese lyrics. Nor did they realize that the songwriter wrote “Sukiyaki” in response to the failure of Japanese protests against American military presence in Japan.

For many, the song had a timeless sweetness about it, a soft melody and upbeat rhythm with a message: to smile amid hardship, a call to make the most of your life. The song even had whistling—a lost art of making music with one’s lips.

My uncle loved this song. He was fluent in Japanese and English, served in the U. S. Army as a translator in the Pacific during World War II, and tried to balance his love of two countries. I grin when I imagine him, a 50-year-old man going into the local record store and proudly buying a “45” record of the top summer hit.

“Sukiyaki” was about lost love, remembering happy times but now feeling alone. The singer looks up, counts the stars with tearful eyes. But happiness lies beyond the clouds, above the sky. So look up and tears won’t fall.

Japan was rebuilding after the war and was about to reenter the world stage. A spirit of starting anew swept that nation and spread across the Pacific.

Japanese Americans adopted a similar spirit of renewal, despite the loss and sadness of their personal histories. It was time for a fresh start. Good fortune was beyond the horizon. Look up and the tears won’t fall.

“Sukiyaki” helped my family—they began to lose their sense of shame following the wartime relocation. My parents smiled when they heard the song on the shed radio. Perhaps they were no longer humiliated, their wounds were healing.

Many still harbored ill feelings against the Japanese following the war. But they were growing older. A new, younger America was moving on, accepting a Japanese song and lyrics by making it the No. 1 song in America.

Can a pop song change cultural and social definitions? Or is it an indicator of shifting attitudes? For a Japanese American farm boy in 1963, a song meant a new world was opening.

(Note: The name “Sukiyaki” was invented for an American audience—it was simple and easier for DJs to pronounce. The real title was “Ue o muite arukoo.” Sukiyaki is a type of Japanese stew.)

*This article was originally published in the Fresno Bee on July 20, 2013.

© 2013 David Mas Masumoto