Read Part 1 >>

The Queries. These queries are haunting. Hearing echoes of internment redress, listen closely: “Why them [Japanese Americans] and not me?”—the African American, highlighting the unredressed legacy of slavery and continuing discrimination. “Why the Japanese Americans before the Native Hawaiians?”—the Hawaiian sovereignty advocate, highlighting redress not as a civil right but as a human rights response to American colonialism. And why not Japanese Latin Americans or Filipino War Vets, still waiting after all these years. “Is it too late for me”—the Korean and East Timor women? The questions resonate for us: “Why us, not others?” And if others, “when and how?”

And despite attacks that “all this is just about special privileges for minorities and legal blackmail of taxpayers,” we know differently. So, two practical questions arise: 1) Looking forward, how is all this relevant to us here and to Asian Pacific Americans more broadly?; and 2) What can be done—what should we do? Let’s start with an observation: The long-term legacy of redress, beyond vindication for Japanese Americans, is still evolving. And how it evolves today and tomorrow depends partly on how “we”—those who have benefitted even indirectly from the politics of redress uplifting Asian Americans and those who possess a commitment to civil liberties, all of us here—it depends partly on how we carry forth and contribute to on-going reparative justice struggles of others.

Why do I say this? How many of you have heard, or said, about the mass incarceration, “we will never let it happen again, we must be vigilant?” Most of us, me included. In Hawai`i a few years ago, every speaker at the Day of Remembrance said those exact words. Congresspersons, U.S. Attorney for Civil Rights included. By “it” each speaker meant the internment. “We” (Japanese Americans) will never let “it” (the mass racial incarceration) happen again. To us. We’ve achieved redress; now we’ll be vigilant.

I found myself reacting in two ways. First, “that’s right, knowing what we’ve legally achieved, Japanese Americans will never be interned again.” That’s truly good.

My second reaction is that something is missing from this thinking. It’s too passive. It sounds like saying it’s enough to tell the story, commemorate achievements, and stand guard against mistreatment of Japanese Americans—all of which are important. But, instead of saying “we will never let it happen again to us”—shouldn’t we be saying more encompassingly, “we will never let deep injustice under the falsified mantles of `necessity’ or `security’ or `protecting the American way’ happen again—to us, or to anyone?” And if injustice strikes, shouldn’t we be saying, “we will help transform history into action and help others seek redress for their suffering…these things must not happen again…to anyone.”

If so, that changes everything. It refocuses how we think and what we do onto the present and future, and onto ourselves plus others. We become historian educators and also agents of justice for the future, because real, hard injustices are occurring all around us every day—to Asian Pacific Americans and other communities and then beyond.

Legacy. With this in mind, a suggestion. The legacy of Japanese American redress can be this: Japanese Americans achieved deserved redress, and IN ADDITION, we Asian and Pacific Americans and compatriots collectively are turning the lessons learned, the political and economic capital gained, the alliances forged and the spirit renewed, into many small and some grand advances in the face of continuing social injustices on the West Coast, across America and across oceans. That would be a legacy that is worthy of who we are and who we can be—acting firmly in our own interests, and then beyond, collaboratively, in the justice interests of others.

But what does this mean practically? Asian American communities are diverse. The challenges far-reaching. I have several suggestions about what we might do in the U.S. But our wonderful closing plenary will speak to this. So I’ll focus my remaining thoughts on a global emanation from the Civil Liberties Act: “redress for other communities elsewhere”. It responds to “why them, not us;” and “is there time for me”.

Last year in South Korea I spoke with eight surviving Korean military sex slaves (also called Comfort Women) subjected to unspeakable horror during WWII. Japan denied everything for decades. Stigmatized, the survivors suffered in silence—most, no spouses or children; menial work, stark hovels for housing. Until they and lawyers, scholars and organizers pushed their story into international consciousness—starting with a lawsuit, followed by human rights tribunals, educational forums, art exhibitions and media stories (and now a compelling comfort women museum).

The women survivors are now assessing strategic next (and perhaps last) steps for still awaited redress. In their late 80s, they still demonstrate every Wednesday before the Japan Consulate in Seoul. I was asked at one such demonstration to speak to the women and their advocates as a Japanese American who worked on “U.S. internment redress.” (And that’s the term their translator used). I was then invited to their home in Seoul’s outskirts. There I saw a framed photo of Congressperson Mike Honda (a former internee). Honda, with support from Asian American groups, had orchestrated the successful fight to get the U.S. Congress to demand full redress by Japan. The women also told me that two among them were going to the United Nations in New York to seek support. And they wanted to know how “you all (Asian Americans) got the most powerful country in the world to step up; and what you folks now can do to help us keep fighting…not only for us few remaining survivors but for women everywhere sexually violated during war?”

I also met with Korean families still suffering from the April 3rd 1948-51 grand massacre of thirty thousand Jeju Island residents by the South Korean military and largely police during U.S. “peacetime” occupation and supervision—“scorched earth destruction of lives and villages,” suffering persisting over generations, still not adequately redressed. They wanted to know what they can draw from the political and human dynamics of U.S.-Japanese American redress. They desire to convey to the world their devastating story and their justice claims, including the significant yet unacknowledged role of the U.S. And they ask for our insights and support for full redress and for a “peace island” amid ramped up hostilities.

And last year I and others authored a friend-of-the court brief to the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on behalf of Micronesians in Hawai`i who are being cut off from government-supported medical health insurance (the only group now without such insurance; many dying prematurely or necessarily). What’s not acknowledged is that their presence here in the United States is a justice (or injustice) issue—suffering horrendous health problems (following U.S. nuclear bomb testing) and purposely destabilized in their homelands by the U.S. (as trustee) in order to perpetuate their countries’ economic and healthcare dependence on the U.S. to enable continued U.S. military access in the Pacific. Micronesians have a compact with the U.S. allowing free access but are nevertheless often described in pejorative terms as immigrants-seeking-handouts—ostensibly justifying harsh treatment. Their presence and treatment should be seen partly as a redress justice issue—as the U.S. making good on the long-standing unfulfilled promises.

Our amicus brief advanced these arguments by starting with the Japanese American redress story. We did so because that story resonates with Micronesian communities, well beyond the courtroom, providing them a language and concepts for organizing and pressing their health care claims as justice issues. And they are asking for more engagement and support from those linked to internment redress.

These are just three global examples—historically alive today—not only of the relevance of Japanese American redress but also of the call to Asian Pacific American communities here on U.S. soil to continue to tell the story and to step up to aid other communities in their struggles for social healing. I have a list of specific suggestions. But time is short so I’ll end simply by suggesting this: Our responses to the pressing calls of others for engagement in the U.S. and across international borders—in words and ideas, in outreach and actions—may well be key to the living legacy not only of Japanese American redress but also, indeed, what it means to be Asian Americans.

Two thousand years ago Rabbi Hillel’s poem got it right: “If I am not for myself, who will be? If I am not for others, what am I? If not now, when?”

* Note: Spoken presentation. Not to be cited as authority.

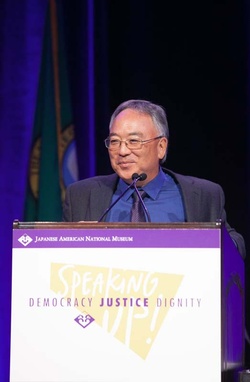

*Eric K. Yamamoto was the keynote speaker at the Luncheon Banquet on July 6, 2013 at JANM’s National Conference, Speaking Up! Democracy, Justice, Dignity in Seattle, Washington. The video of his speech will be available on Discover Nikkei soon!

© 2013 Eric K. Yamamoto