Although my parents and I visited Watsonville every summer during my childhood, I only became familiar with the name—Pajaro Valley—of this region on the central California coast much later, in my thirties. Before then, Watsonville was just the inaka, the country, where we would travel north several hours from Los Angeles in my father’s white van that carried gardener’s tools most of the year. My father was born in Watsonville but had moved to Japan after his grandfather was killed by a horse on the farm. After World War II, my father returned to Watsonville, in his late teens, and before making his way to his new life in Southern California lived with his aunt and uncle and many cousins in a pristine white Victorian house off of Highway 1.

For this city girl, Watsonville was a magical place. The rows of lettuce around my relatives’ house resembled the heads of giant groundhogs surveying the rich soil. Since it was summer and in the sixties, before the off-season varieties had been fully developed, strawberries were only found within the confines of plastic containers in the large freezer in the shed. My distant cousins and I ran around inside and outside the large house. One favorite spot for all the grandchildren, great-nephews, and great-nieces was just on the side of the curved staircase on the first floor, where comic books were stacked like a pile of gold. Just where my great-aunt got all those comic books—and they were recent ones, too—was unknown. They seemed to just secretly appear in this country farmhouse.

As I grew older, I began to notice the name “Watsonville, California” affixed to plastic strawberry containers, or shells, but didn’t think much of it. Watsonville, Castroville, Salinas, Gilroy—they seemed like the generic inaka where fruits and vegetables came from, like a giant icebox serving the city folk. Then, in college in Northern California, I caught the liberation theology fever and went on an overnighter with a group led by our campus pastor to a farm in—where else?—Watsonville. We slept in the home of a farm worker, visited the local United Farm Workers (UFW) field office, and walked amidst mushroom and cauliflower fields. This was a different Watsonville than I had ever known. I didn’t attempt to reconcile the childhood memories of sweet frozen strawberries in the packinghouse freezer with the more political and complex issues of labor in a farm community. In my mind, the two worlds—family farm and migrant farm workers—were parallel, unable to coexist separately, like two different crops on the same piece of land.

Almost two decades later, I visit Watsonville again, but this time as a researcher for a prominent Nisei farmer’s memoir. My relatives’ beautiful Victorian home has been abandoned, heavily damaged by years of rain. The devastating Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989 leveled downtown buildings, and ten year later, gallant yet scattershot efforts at reconstruction are evident on Main Street. I found that to do research in the area, I couldn’t stop in at one historic society or one religious organization. People were not only separated by class, race, and cemeteries, but by religion and family connections. Some old-timers were still around to tell me how the seasonal rains would flood their homes and businesses, causing families to move merchandise and even pianos onto the second floor. I heard accounts of migrant farmers moving from one acreage to another, creating patchwork strawberry farms in light of alien land laws outlawing the Japanese from buying land. Yet I needed something more definitive about the Japanese American presence in the area.

There were individual oral histories filed in local and college libraries and Sandy Lydon’s The Japanese in the Monterey Bay Region, which provided an important timeline of events and photos before and after World War II. But beyond that, my search did not result in much.

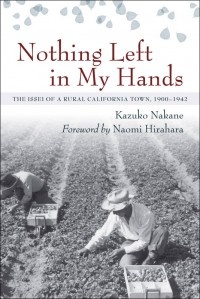

I did discover one invaluable source back in a library in Los Angeles—a copy of Nothing Left in My Hands, published by a small publisher, Young Pine Press. It was a slim volume, barely over a hundred pages, yet carefully constructed, as if each word had been selected from a handset type box. I was instantly captivated by its simplicity, earnestness, and deep research. The only problem was its availability. Out of print, it seemed even unavailable for sale as a used book. The library where I found it only had it as a noncirculating reference book.

So I took notes, photocopied excerpts, and soaked in its elegant and simple tone while sitting at a desk in the library. Nothing Left in My Hands, I thought, would be just one of those precious stones in a few libraries, waiting to be excavated. And I personally was glad to have experienced it.

Almost ten years later, an email comes. Heyday Books is asking me to fashion a foreword for the reprinting of this book, Nothing Left in My Hands. I’m delighted. It is no surprise that Heyday Books, with its commitment to California and rural history, would be the one to give a second life to Kazuko Nakane’s book and her material.

The value of Nothing Left in My Hands is multiple. First of all, it’s one of the few published sources of pre–World War II Issei historic accounts of the Pajaro Valley and farming communities. At her foundation are many familiar sources, in both English and Japanese. Being a native from Japan and bilingual, Nakane is able to deftly weave and condense the important facts to provide a good portrait of the region from the early 1900s to 1940.

Appropriately peppering her narrative are excerpts from oral history interviews she conducted with predominantly Japanese-speaking Issei. While some scholars are suspicious of including these types of accounts in history books, I’ve always acknowledged the power of such information collection, especially when the interviews involve immigrants and are conducted in-language. Multiple factors, notwithstanding the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, led those of Japanese ancestry to distance themselves from the first tongue of the Issei, the Japanese language. As a result, a gulf has emerged between the first and third generations, causing the latter to depend only on secondhand recollections to piece together what really happened before the war.

These interviews are not comprehensive, yet they are wide enough to provide those essential concrete details that give the text life. It is obvious that Nakane respects her subjects immensely. In keeping with her careful work, Nothing Left in My Hands is not purely a celebration, but a documentation of harsh realities. Instances of gambling, prostitution, and labor protests are all meticulously documented.

Geography and the changing continuum of agriculture are also important. Through the study of Pajaro Valley, you can see the transfer of labor and immigration patterns. The contributions of the early Chinese and Dalmatians (Croatians from Yugoslavia) and later Pilipino and Mexican laborers serve as bookends to the entry of agricultural workers from Japan. The Japanese labor force has steadily transitioned from buranketto katsuji, migrants carrying blankets on their shoulders, to sharecroppers and cash tenant farmers and to the independent farmers of today.

Women and mothers are not forgotten. Again, through the practice of oral history, Nakane has also provided the reader with searing snapshots of the lives of Issei women who traveled across the Pacific to marry men who were virtually strangers.

Certainly other agricultural areas along the Pacific Coast share similar stories. But there’s something about Watsonville—perhaps its proximity to the ocean or its gentle wildness—that invites comparisons to the coast of Japan. Or perhaps it’s my own childhood nostalgia that only deepens my affinity for the area.

While many outlying communities closer to or within the Silicon Valley have fallen to high-tech development, Watsonville has held onto its agricultural roots—albeit with the pressure of large housing projects pressing against its boundaries. Because of this long tradition, the tale of Pajaro Valley has added weight. Indeed, as we read the accounts of these pre–World War II farmers, other faces—the tired, calloused men and women escaping the Dust Bowl in the thirties, the stooped images of today’s strawberry pickers in the fields—seem to have more definition. Nothing Left in My Hands is the story of one specific ethnic group during a window of time, yet a story that explains much of what came before and what came after.

*Originally published as the Foreword from Nothing Left in My Hands: The Issei of a Rural California Town, 1900-1942 by Kazuko Nakane (Heyday Books, 2008).

© 2008 Naomi Hirahara