Read Part 5 >>

EL MUNDO TRES

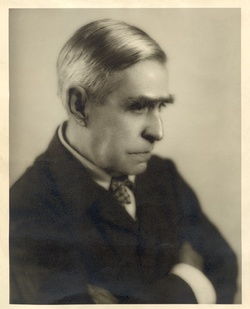

Several anthropologists assure us that Japanese influence on Mesoamerican cultures began in prehistory.1 In Mexico, writer-poet-painter José Juan Tablada (1871-1945),2 is seen as the most notable exponent of Japonisme.3 In his youth, Tablada attended the Mexican Military College for a few months and then entered the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, where he learned painting. Upon graduation, he held a few modest jobs in the National Railway system, and began writing poetry, and many articles for several major Mexican papers.

His biographers do not tell us when or how he became interested in Japanese art. Like many other westerners, the fancies of exoticism, sensuality, opium and pagodas first attracted him, and in 1900 he decided to visit Japan.4 There, he met the poet Okada Asataro from whom Tablada learnt about poetic forms such as uta, haiku and tanka as well as ukiyo-e. He fell in love with the Japanese short-form poems, began creating his own in Spanish, and started collecting ukiyo-e, feverously.

He returned to Japan in 1910, and expanded his knowledge about the country’s culture. Next, he went to Paris, where he remained for almost a year, during which he met French Japoniste Edmond de Goncourt, and fell under his influence. Tablada was able to raise his collection of ukiyo-e to more than 200 items.5 While in Paris, he also befriended and influenced several Spanish and Mexican artists, including muralist Diego Rivera, then in his early cubist stage.

Back in Mexico, in 1913, Tablada was named Professor of Oriental Arts at the Academia de Bellas Artes. However, in the same year he satirized incoming Mexican President, Francisco I. Madero, and to avoid being assassinated, he fled to the United States. He settled in New York in 1914, where he hobnobbed with other Mexican émigrés such as Miguel Covarrubias, Jose Clemente Orozco, and again Rivera, now a rebel, avant-garde communist.6 Tablada opened a bookstore where he also traded in art, and became the ‘Mandarin’ of the Latin art community.

He exerted a strong influence on both Mexican writers, whom he introduced to the delights of haiku; and on painters, whom he infected with his ideas about ukiyo-e. In memory of his mentor De Goncourt, he wrote and published a history of Hiroshige, a task that he claimed he had inherited from De Goncourt. He also translated into Spanish a number of Japanese uta, including work by the poetess Ono-no-Komichi- one of the six geniuses of the Kokinshu,7 and some pieces by B.H. Chamberlain in Japanese Poetry.

By the 1920’s, haiku—or its sometimes rhymed Spanish-language version—had become a very popular form of poetry in Mexico. In 1914, Tablada received the Zui-jo-sho Medal and Distinction of the 4th Order, from the Japanese Empire. In January 1923, the New York Times cultural supplement published a selection of his poems, translated into English, with a prologue by Thomas Walsh.

In 1919 he published his extraordinary small book of thirty-seven haiku: Un Día (A Day).8 He illustrated every poem in each book by hand with a delightful oval-shaped watercolor emulating haiga-haikai- illustrated poems done with the same brush. He issued 200 copies, which, nonetheless, meant 7,400 original pictures.

By 1936, having written close to 10,000 articles, several books, and composed over 2,000 poems, many in the haiku style, he decided to spend a few years in Mexico and Havana, but always yearning for his beloved New York, he returned in 1944, and died there in 1945. His remains were taken to Mexico and placed in the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres (The Mausoleum for Illustrious Persons).

A PREMATURE OBIT

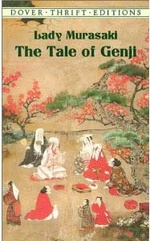

Several writers have led us to believe that Japonisme died around 1914, together with art nouveau. But digging further, one keeps finding the cultural influence of Japan on western arts, in one or another form, way beyond the date of the movements’ purported expiration. For example: between 1925 and 1933 Time magazine, gave much attention in its book section to the translation of the Tale of Genji9 by British scholar Arthur Waley. In its July 3, 1933 issue, the magazine wrote: “When British Scholar Arthur David Waley brought out the first volume of his translation (1925), critics tumbled over themselves to get within wreath-throwing distance.”10 The wreath-throwing and further works by Waley created a Hokusai-style Wave of interest among the western literati, particularly in America. By 1933, Waley’s Tale telling had found an outstanding place in English literature and culture.11

In the heart of avant-garde modernism, a new romance flourished—and lasted well into the early 1940’s. In both Great Britain and America you can see many of the treasured pieces of Japanese art or of Japonisme still in the hands of private owners.12 Like Amaterasu, Japonisme might have run into the Olympian cave during the hostile days of the Pacific War, but after the American occupation of Japan, it was resurrected, however slowly.

In Japan, many art objects were ‘liberated’, or honestly acquired, by members of the occupying forces, and many of the occupants built lasting interests in the Japanese culture and its people. Then Zen, Sony, Toyota, Akira Kurosawa, Pokémon, ocha, and Robotech appeared—and together with karate, animé, manga and Japanese management styles, the fun began again. But all of that, and the reverse effect of Japonisme on Japan, are topics for a really voluminous tome yet to appear.

My special gratitude goes to Dr. Gabriel P. Weisberg, and to Mexican Educational TV producer Sergio Moreno Sotelo, for their invaluable help for this piece. However, any and all mistakes are those of the author.

Notes:

1. Though much has been written on Japanese pre-Columbian influence in Mesoamerica, please see as an example, Celia Heil’s article on Mexican lacquers “The Pre-Columbian Lacquer of West Mexico,” NEARA Journal, Vol. XXX, 1&2 (1995): 32-39.

2. Enciclopedia de México, Vol XI, (Mexico, 1978), 541-2.

3. Atsuko Tanabe, El Japonismo de José Juan Tablada, (Mexico: Universidad Nacional de Mexico, 1981).

4. Ce Rosenow, “Different Songs Sung Together. The Impact of Translation on the Poetry of José Juan Tablada,” www.arts.monash.edu.au/others/coloquy/issue9/rosenow.pdf

5. Initially, Tablada’s collection, which included some examples of explicit pornography, gathered dust at the Castillo de Chapultepec; it is currently housed at the Biblioteca Nacional de México, together with most of his literary work.

6. One cannot fail to observe the influence of Japonisme in the works of Tablada’s friends, such as Miguel Covarrubias, who in his books Mexico South, (Knopf, 1946) and Island of Bali, (Knopf, 1946), for example, delights us with a brilliant handling of line and space, and the use of color in depicting the native peoples and their indigenous costumes.

7. The Kokinsu or Kokin Wakashu is one of the earliest Japanese anthologies of short poems, conceived by Emperor Uda, during his reign (887-897), and commanded by his son Emperor Daigo, around 905.

8. Colombia La Esperanza, Febrero-Mayo 1919. http://www.ahapoetry.com/pp0301..htm

9. Haruo Shirane, ed., Envisioning The Tale of Genji, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

10. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,745773,00.html#ixzz1F5Os1BGb. Among those celebrating Waley’s accomplishment was the literary queen of those years, Virginia Woolf.

11. John Walter de Gruchy, Orienting Arthur Waley—Japonism, Orientalism, and the Creation of Japanese Literature in English, (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2003). Note especially Dr. Haruo Shirane’s comment on the jacket’s back cover.

12. In America, one can frequently enjoy examples of both Japonaiserie and Japonisme in the one-hour weekly PBS program Antiques Roadshow.

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/archive/index.html

Britain’s BBC has a similar half-hour show: www.bbc.co.uk/antiques.

© 2012 Edward Moreno