On February 9, 1885, the first official Japanese migrants arrived in Hawai’i. Before an audience that included King David Kalakaua, they reportedly celebrated their arrival with a sumo match.

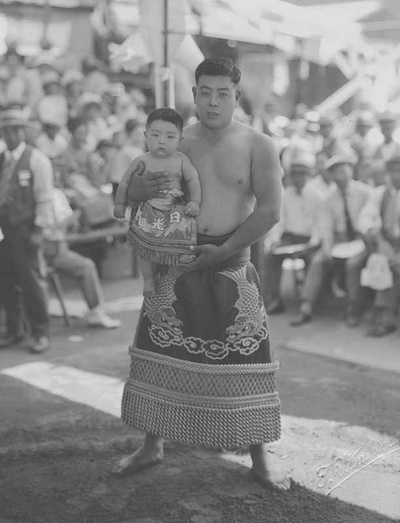

Takichi Kato holds his son Mitsuo Kato after a ceremony held at a Sumo match, Los Angeles, 1925-1926 (Gift of Masako Kato, 2000.416.1).

Rooted in two thousand years of agrarian, Shinto tradition, sumo was transported to America by the Issei, who organized inter-island tournaments in Hawai’i as early as 1896, and major competitions between Hawai’i and mainland sumotori1 by the 1920s. Originally a harvest ritual, sumo was enjoyed as sport and entertainment among the early immigrant communities—as a centerpiece of social events, as a source of cultural identity, and as a vehicle through which to instill Japanese values in their American-born children. While sumo continued within America’s concentration camps during the World War II, its prominence in Japanese American communities diminished afterwards as many Nisei and their children shifted away from Japanese cultural forms and the pre-war sumo venues were dismantled when historical communities were redeveloped.2 In recent decades, the sport of sumo has enjoyed international growth, and Japanese Americans—along with participants and fans from around the world—have engaged its new popularity and changing face in varying ways.

In his introduction to More than a Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community, editor Brian Niiya writes, “Sport looms large in the history of Japanese Americans. In every period of Japanese American history…sport has been part of the fabric of Japanese American life.” Sumo is thus as strong a thread as any running through the “fabric” of Japanese America. And the kesho mawashi —the ritual “threads” of sumo—are wonderfully graphic material manifestations of the significance of sumo to the communities who have contributed to its transformation in the U.S. and abroad.

Kesho mawashi are the ceremonial “aprons” worn by the five highest ranked wrestlers during the Dohyo-iri, the “entering the ring” ritual of sumo tournaments. Made of silk and hemmed with heavy gold tassels, kesho mawashi are elaborately embroidered with designs that reflect the wrestler’s character, culture, and/or the organization that sponsors him. In June 2008, for the first time since 1981, Los Angeles was the venue for Japanese professional sumo wrestling presented by the Nihon Sumo Kyokai, Japanese Sumo Association. The website for the event featured portraits of the competitors wearing kesho mawashi with designs that highlighted the diversity of the field. For example, emblazoned on the kesho mawashi of Baruto (Kaido Hoovelson) of Estonia was something resembling a Viking helmet; the one worn by Kimu-Kasugao (Kim Sung Tak) of Korea displayed the crossed flags of South Korea and Japan; and the one of Ama (Bavaznyoun Byambadorj) of Mongolia featured a white-winged horse in front of a red sun.

The Japanese American National Museum’s permanent collection includes two kesho-mawashi of dramatically differing scale, each with its own intriguing history, but that together reflect the transformation of sumo internationally and the shifting involvement of Japanese Americans in the sport.

Child's kesho mawashi worn by Mitsuo Kato in the ceremony documented in the photograph above (Gift of the Masako Kato Family, 2000.89.1).

The older (and smaller) of the two was worn by one-year-old Nisei Mitsuo Kato in the 1920s. Mitsuo’s father, Takichi Kato, was a member of Butokukai, the North American Martial Virtue Society. An influential group that encompassed over 40 branches and a membership of more than 10,000 throughout the West Coast, Butokukai organized tournaments between visiting Japanese athletes and local Issei and Nisei. Mitsuo, shown above with his father, was dressed in this kesho mawashi for a ritual performed at the beginning of tournaments in which the male babies born in that year were paraded across the ring and thus bestowed with good health and prosperity.

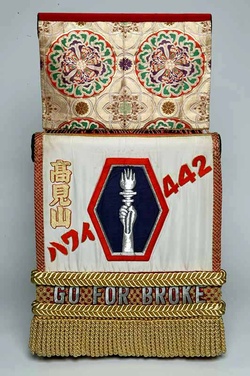

Jesse Kuhaulua's first kesho mawashi was given to him by 442nd Regimental Combat Team veterans (Gift of Azumazeki Oyakata, 2004.80.1).

The second kesho mawashi in the Museum’s collection was made for 19-year-old Jesse Kuhaulua when he left his hometown of Happy Valley, Maui, to enter the world of professional Japanese sumo. In 1964, he debuted as Takamiyama, and he became the first foreign-born sumotori to win a championship. His first kesho mawashi was given to him by veterans of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Inscribed in English and Japanese with the 442’s logo and motto, “Go For Broke,” it expresses the veterans’ pride in their Japanese heritage, their own remarkable military achievements as Japanese Americans, and their regional identification with a promising, young, “local” athlete.

These two kesho mawashi, products of distinctly different social and cultural contexts (not to mention their contrasting sizes and age), constitute pieces of the dynamic fabric of Japanese American community life. The 442nd veterans, the same generation as little Mitsuo Kato, grew up with sumo as a community tradition, experienced the sting of anti-Japanese sentiment, challenged public sentiment through their actions, and in their support of the aspirations of Jesse Kuhaulua demonstrated both their admiration for tradition and their active participation in its transformation.

Notes:

1. Wrestlers

2. See Brian Niiya’s introduction to his edited volume More Than a Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2000) and Eiichiro Azuma, “Social History of Kendo and Sumo in Japanese America” in More Than a Game.

© 2009 Japanese American National Museum