The Bronzeville era of Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo lasted about three short years during World War II. But before I talk about Bronzeville, it should be noted that African Americans occupied the area that we now call Little Tokyo more than 100 years ago. To illustrate this point, the modern Pentecostal movement, which was started by Rev. William J. Seymour, an African American minister from Texas, had its beginning in 1906 in an abandoned warehouse on Azusa Street in the area we now call Little Tokyo because back in the early 1900s, this area was considered an African American district. A December 22, 1904, Los Angeles Times article describes this area as “the negro tenderloin,” and makes references to a tamale stand and a “Japanese dive,” indicating this area was multicultural.

Fast forward to the 1940s, Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941. By the spring of 1942, the US government issued evacuation and incarceration orders for Japanese Americans, so Japantowns up and down the West Cost became ghost towns. A July 12, 1942 Los Angeles Times article reported that white Little Tokyo building owners were discussing plans to turn Little Tokyo into a Latin American section, housing representatives from the Latin American consulates and trade organizations. This didn’t happen. Instead, thousands of African Americans, mainly from the Deep South, came to the West Coast to work in the defense industry, which was facing a huge labor shortage.

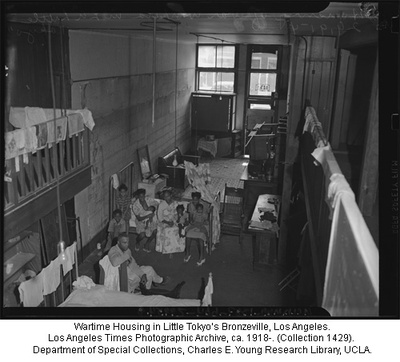

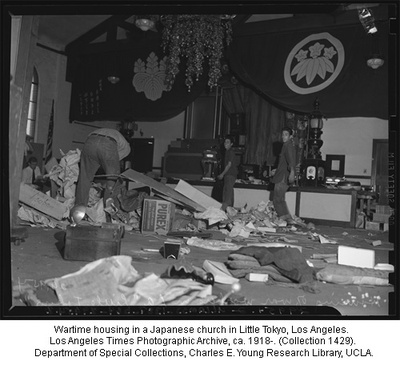

These African Americans were forced to live in the vacant Japantowns because most areas had restrictive housing covenants, barring people of color from living in white neighborhoods. In Little Tokyo, which had once housed about 30,000 Japanese Americans, the Los Angeles County Health Department estimated that there were now 80,000 African Americans, with a few Latinos, occupying that area. Everything from vacant stores, garages, and churches and temples became makeshift living quarters. Slum conditions developed as sometimes 16 people lived in one room or 40 people shared one bathroom. The term “hot beds” came into use to describe the situation where a bed was immediately taken over by someone else as soon as a person got up.

This situation was not unique to Little Tokyo. Similar patterns played out in other Japantowns. The 1943-1944 Biennial Report by the California State Division of Immigration and Housing states that:

Negroes are moving into the deserted Japtown districts of our metropolitan centers in vast numbers, and conditions of sanitation are generally poor, and overcrowding is a major difficulty.

We have succeeded in cleaning out several of the smaller abandoned Japtown districts throughout California, and through abatement actions and misdemeanor prosecutions, we have had a large number of old dilapidated frame shacks razed to make way for new buildings.

By June 3, 1943, the California Eagle, an African American newspaper in Los Angeles, printed an editorial with the headline “Ghetto Housing Must Go!” and described Little Tokyo as “rancid” and “rat-infested.” To assist these newcomers, the Los Angeles County Social Services Department formed a special Little Tokyo Committee. Katherine Kaplan, Little Tokyo Committee chair, wrote to then-California Governor Earl Warren, asking for state assistance. She reported overcrowded conditions were creating conditions “ripe for epidemics, vice and race riots.” The special committee also helped form Pilgrim House, a social service agency, housed at the old Union Church, which today is the Union Center for the Arts. Pilgrim House provided services in health, sanitation, education, housing, and employment referrals.

In early June 1943, Anglo servicemen clashed with Latino youths in what is referred to as the “Zoot Suit” Riots, and the chaos spread to Little Tokyo. One of the most graphic incidents reported is in the June 17, 1943, California Eagle, which said a mob gouged out an eye of Lewis W. Jackson, 23, an African American resident of Little Tokyo, who had moved from Louisiana and was working in the shipyards.

As the African American housing situation got worse, Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron held emergency housing meetings. City Health Office inspectors found high incidents of tuberculosis and venereal diseases in Little Tokyo, and then served 140 abatement notices ordering the people to move out due to substandard conditions. In late 1943, the Federal Housing Authority proposed to build temporary housing for African Americans in the Willowbrook area, a then-white neighborhood next to Watts and Compton. The white residents protested, claiming their property value would go down. There were threats of race riots and reviving the Ku Klux Klan. Everyone from the sheriff to the governor monitored this situation.

In October 1943, Leonard Christmas, an African American businessman, who ran a hotel in Little Tokyo, announced at a Little Tokyo Committee meeting that the "district is no longer Little Tokyo." That same month, the Bronzeville Chamber of Commerce opened an office on San Pedro Street.

With so many people in Bronzeville, there was an active night life. One of the best known Bronezville clubs was Shepp’s Playhouse, on the corner of First and Los Angeles streets, currently the Kyoto Hotel. The likes of Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Count Basie, and Joe Louis frequented Shepp’s. Big names like Charley Parker and the Lionel Hampton Band stayed at the Civic Hotel, on the corner of First and San Pedro. After the war, it became the Miyako Hotel, which was later torn down to make way for the Kajima Building. It was at the Civic Hotel that Charley Parker had his nervous breakdown, set his mattress on fire, and then, in a drug haze, walked into the hotel lobby naked.

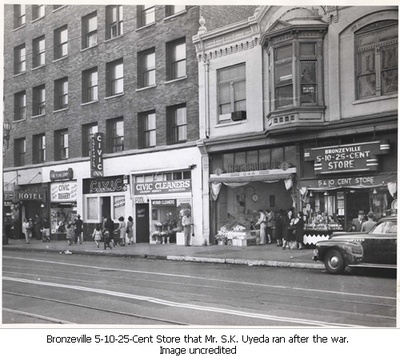

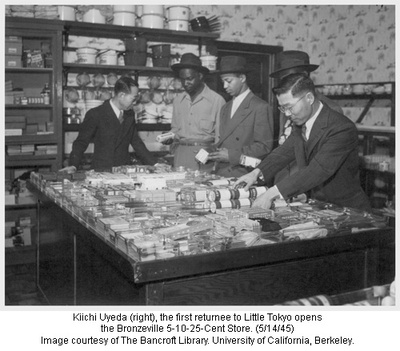

By early 1945, the United States government was allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast For the most part, the transition from Bronzeville back to Little Tokyo went smoothly. Either Japanese Americans bought out the leases of Bronzeville businesses or buildings owners didn’t renew lease agreements with the African Americans.

Mr. Kiichiro Uyeda, who is recognized as the first returning Japanese American to re-open a business in the area, bought the lease to the Bronzeville 5-10-25-Cent Store and attempted to foster positive race relations by hiring African American workers. In turn, African Americans such as Samuel Evans, who ran the Bamboo Room on First and San Pedro, hired returning Japanese Americans.

The Los Angeles Tribune, an African American newspaper, took out an employment ad in the Pacific Citizen, the Japanese American Citizens League’s newspaper. Award-winning writer Hisaye Yamamoto was one of three Japanese Americans hired at the Tribune. Award-winning playwright Wakako Yamauchi babysat the children of Almena Lomax, Tribune publisher and editor. Later, Crossroads, a Japanese American publication, was printed at the Tribune plant.

While Japanese Americans were busy re-establishing their lives, African Americans faced a new problem. With the war industry slowing down, African American war workers were being laid off. As unemployment soared, so did crime. In 1947, the Japanese Business Men’s Association hired two Nisei veterans to patrol Bronzeville/Little Tokyo after dark, and racial tension flared, prompting a community meeting. The March 1947 meeting was covered by African American newspapers, including the Chicago Defender, and the mainstream media. The chief of police promised more plain clothes detectives in the area.

There were a handful of lawsuits that Japanese Americans filed after the war, mostly to reclaim their properties. The Los Angeles Hompa Hongwanji, also known as Nishi Hongwanji, became embroiled in three lawsuits. One involved the Providence Baptist Association, which had opened an African American church and theology school inside Nishi Hongwangi, currently the Japanese American National Museum. The second lawsuit involved Dr. George Hill Hodel, who had a medical clinic in the Nishi building; and the third involved Reverend Julius Goldwater, who had overseen the Nishi Hongwanji finances during the war. Another lawsuit involved the New Olympic Hotel against Western Loan & Building Company. During the war, the New Olympic became the Downtown Hotel, and Charley Parker also roomed at the Downtown Hotel. After the war, the Japanese American consortium renamed it the Olympic Hotel. Today, the Los Angeles Police Department’s Parker Center is located there.

By 1950, Little Tokyo had some semblance of its pre-war period. However, African Americans did not disappear from Little Tokyo altogether. Many continued to live in residential hotels such as the Alan Hotel, which later got torn down in the 1970s to make way for Parker Center. The longest running Bronzeville era business was that of the late James Hodge, who had opened a newspaper stand on the corner of First and San Pedro streets in 1942. His business endured well into the 1980s where he could be seen selling everything from the Los Angeles Times to the Kashu Mainichi. In the 1983 book Little Tokyo: One Hundred Years in Pictures, Hodge described the Bronzeville period as: “This neighborhood here was nightclubs and gambling and prostitutes and pimps. But they weren’t like today. They were civilized. The sun never went down in this neighborhood. Guys were spending money with both hands. It was real exciting . . . but it only lasted about three years.”

For more information on Bronzeville, visit the Bronzeville project Web site.

For more photos of Bronzeville, visit the Calisphere Web site.

* Martha Nakagawa image credit: Mario Reyes

** Martha Nakagawa is one of the panelists in a presentation titled "Sharing a Historic Space: African Americans, Native Americans, and Nikkei" at the Enduring Communities National Conference on July 3-6, 2008 in Denver, CO. -ed. Enduring Communities is a project of the Japanese American National Museum.

© 2008 Martha Nakagawa