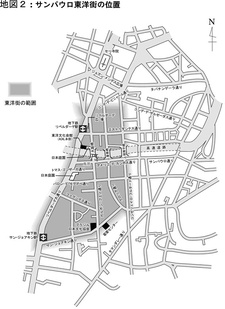

Exiting out of Libertade station on the São Paulo South-North subway line, one arrives in a neighborhood filled with extravagant restaurant billboards and supermarkets selling Japanese, Chinese, and Korea products and ingredients. This is the center of Bairro Oriental, Libertade Plaza (Photo 6-1). Galvão Bueno Street runs south from here and at night, the street is lit up with the neon signs of shops along with the red Suzuran lamps. Once known as the largest Japantown in the world, Bairro Oriental (“Oriental neighborhood”) is located roughly at the center of São Paulo city and is Libertade District’s main business and tourist area. It spreads from Libertade Plaza along Galvão Bueno Street, past Glória Street, to São Joaquim Street (Reference Map 1,2).1

Even before the war, there was a large concentration of Nikkei in the current Bairro Oriental area. Many Nikkei parents with children thought well of the area, especially because of the Nikkei schools, boarding houses, and small businesses in Bairro Oriental. As I mentioned in previous articles, due to the eviction order in 1942, many Nikkei living in the Liberdade District, especially the Conde District, had no choice but to move out to the suburbs and inland areas. However, there were many people who returned to Bairro Oriental relatively quickly after the war. Further, some avoided the Conde District and resettled in difference parts of the Liberdade District along Galvão Bueno Street and São Joaquim Street. As I mentioned earlier, by the 1930s, the center of Japantown had shifted from Conde de Salzedas Street to Conselheiro Furtado Street. One of the reasons for this shift westward from the familiar Conde de Salzedas Street was because of the steep slope and the flooding caused by it.

Inch up over the hills (Gyosetsu)

The hills in the Conde de Salzedas Street area were so steep that immigrants referred to them with such sayings. The hills must have been a great inconvenience to them.

As I have said, there are currently many schools in the current Bairro Oriental area -around Libertade Plaza, Galvão Bueno Street, and São Joaquim Street- such as Taisho Elementary School, Seishu Gijuku (São Paulo State private school), and the Japanese-Brazilian Women’s Sewing School. Due to the numerous Nikkei schools and the relative closeness to the Conde District, the area is known for crowds of Nikkei roaming the streets.

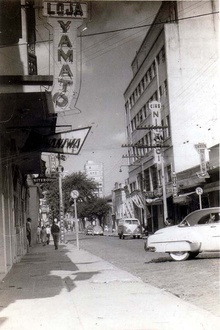

Though today there is no end to the traffic of train cars and people on neon lit Galvão Bueno Street, until the 1950s, roadside trees were being planted along a quiet road described as “In the day, quiet as the night.” Further, due to the lack of cars, children kicked rocks around and played tag and jindori (a game in which the aim is to occupy the other's home base) on the street. Libertade Plaza was once a park with an artificial hill in the center and a bronze statue of Diego Antônio Feijó during the imperial government era atop the hill.

What caused the area to become the new Japantown that replaced the Conde District was definitely the opening of the Cine Niterói on July 23rd, 1953. Cine Niterói was founded by Yoshikazu Tanaka, a grain broker, as Brazil’s first Japanese movie theater. The building had an area of 1500 m² with 5 floors and a basement and was located a little down Galvão Bueno Street from Libertade Plaza (where Osaka Bridge is today). The first floor was the movie theatre Cine Niterói which could hold up to 1500 viewers. From the second floor up, there was a restaurant, a hall, and a hotel; becoming the Nikkei community’s greatest amusement facility. (Photo 6-2) Colonia Geinoshi (History of Art and Entertainment in the Japanese Brazilian Colony, 1986) describes the opening of Cine Niterói as such:

The Galvão Bueno area, with its old road-side trees and dimly lit street lamps, suddenly became a magnificent sight to the people of the day with the completion of this white-walled palace (p.265).

The period after World War II had been a prosperous time for movies around the world, and the Japanese movie industry had followed suit. In 1953, Rashômon, directed by Akira Kurosawa, had won the Grand Prix at the Venice Film Festival and in 1953 Director Kosaburô Yoshimura received the best director’s award at the Cannes Film Festival for his film, Genji Monogatari. The Japanese movie industry was entering into its golden age.

Following Cine Niterói, Nanbei Gekijou (the later Cine Tokyo) opened on the corner of Liberdade Avenue and São Joaquim Street. Further, in 1959, Tanaka’s rival, Kimiyasu Hirata, opened Cine Nippon (capacity of 1600 viewers) and Cine Nikkatsu also began its business. When Niterói first opened, it showed films from different companies such as Daiei, Tôhô, Shôchiku, Shintôhô and Nikkatsu. However, in a few years, it began specializing in Tôhô films. Nippon specialized in Shôchiku, Jóia in Tôhô, and Cine Nikkatsu in Nikkatsu. During Japan’s golden age of movies, this area had four specialized movie theaters competing against each other.

During the aggressive atmosphere and dispute over victory during the war, the Nikkei Brazilian community was denied of amusement and endured through gloomy times. With the opening of Cine Niterói, the Nikkei population burst into joy over the theater. Even the newspapers wrote about the “never-ending lines,” describing the great number of viewers.

Colonia Geinoshi documents the sudden change in the Galvão Bueno area from an ordinary residential district to a bustling Japantown as such.

It isn’t until recently that you feel like you’ve returned to Japan when you go to the Galvão Bueno area. In general, more than half of the passersby are Japanese and the store signs are mostly written in Japanese with kanji and kana. (…) There is a variety of store signs which intrigue passersby such as a sign with a picture of Yujiro Ishihara holding a pistol in front of Cine Niterói and one of Kouji Tsurutain dressed up as a yakuza. The floor above Cine Niterói is the Hotel Niterói, where all the workers and guests are Japanese.

However, the Galvão Bueno area before and soon after the war, prior to Cine Niterói’s construction, was filled with identical houses, which seemed to have been built a century ago. There was only one bar on the street corner and two or three restaurants.

At sunset in those days, friendly-looking people would peek out of their windows to leisurely watch passersby. One could frequently see couples lovingly chat under the trees lining the street, but now there aren’t any of these trees to be seen in the area. The appearance of Cine Niterói transformed the residential area into a shopping district.

By July of 1964, at the bottom of the hill where São Joaquim Street and Galvão Bueno Street intersect, the parent organization of the later Brazil Nihon Bunka Kyôkai (Brazilian-Japanese Culture Association), the São Paulo Bunka Kyôkai (São Paulo Culture Association) Center Building was completed. After the first construction period, the site was 3734 m² and had four floors. However, with many expansion construction projects, the building grew in size.

Some of the main functions of this association in its early days were to host the arrival ceremony of the Crown Prince and Michiko Princess (now the current Emperor and Empress) in May of 1967, the 60th anniversary of Japanese Immigration in June of 1968, and to build the commemoration auditorium for the arrival of the Crown Prince and Princess (completed in September of 1970). Organizations such as the Federation of Prefectural Associations of Japan, the Japanese-Brazilian Welfare Organization of São Paulo, the São Paulo Social Studies Research Facility, the library, the Nikkei art gallery, and the Committee of Industrial Arts would be located within this building. Through such processes, the Brazil Nihon Bunka Kyokai (reorganized in 1968) grew to become an umbrella institution for the Nikkei-Brazilian community.

With the establishment of this “Bunkyo” or “Bunkyo Building,” as it is called (even by Nikkei who couldn’t speak any Japanese) as a community center, the region starting from Libertade Plaza, through Galvão Bueno Street to São Joaquim Street became recognized as a united area by the Nikkei community2. By 1965, Tanaka, the founder of Cine Niterói, Tsuyoshi Mizumoto, and others established the Libertade Shopping District Friendship Association (predecessor to the Libertade Chamber of Commerce and Industry). In this way, this region became a united area, centered around the Friendship Association and Bunkyô, which would later form Bairro Oriental.

Notes:

1. The span of Bairro Oriental is not clear. Bairro Oriental is a bustling commercial district, which is just one area of the administration domain designated as “Libertade.” According to research on the location of the Suzuran lamps, the symbol of this area, tourist guide books from the 70s (Okuyama et.al, pp. 16-17), and interviews with business owners, I believe Bairro Oriental is centered on the Libertade Plaza and spreads north to Dr. Joaquim Mendes Plaza, west to Libertade Avenue, south to São Joaquim Street, and east to Conselheiro Furtado Street (Reference Map 2). However, there are many Nikkei, Chinese, and Korean businesses outside these boundaries.

2. At the symposium led by the Libertade Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 1996, “Libertade 50 years of Transition -‘The Old and the New’ Presented by the Founders of the Area,” it has been confirmed that the existence of the Libertade Shopping District Friendship Association, founded by the owner of Cine Niterói, Yoshikazu Tanaka and others in 1965, and the Nihon Bunka Kyokai prompted the gathering of Nikkei in this area (ACAL, 1996, p.56).

References

OKUYAMA, Keiji(ed.). (Date of publication unknown) São Paulo Toyo-gai Guide [Guide to Oriental Town of São Paulo].

Association for the History of Art and Entertainment in the Japanese Brazilian Colony (1986), Colonia Geinoshi [Association for the History of Art and Entertainment in the Japanese Brazilian Colony].

ACAL (1996) Liberdade. ACAL

© 2007 Sachio Negawa