Even after the Taishō Elementary School, Brazil’s first Nikkei schooling system, moved to San Joaquin Street, the Japantown of the Conde District continued to grow. It is believed that its most prosperous days were between the mid-1930s and around 1940.

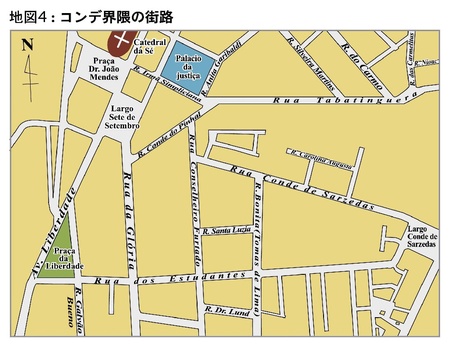

The Japanese community in São Paulo city at this time had risen out of the bleak years of 1914-15. The residents of Conde had “climbed up the hill,” reaching the height of the Conselheiro Furtado era, and advanced to Conde do Pinhal, Tabatingüera, and Irmã Simpliciana. (Handa, 1970, p.572).

It is estimated that around 1933, the Nikkei population of the Conde region had reached to about 600 residents (Handa, 1970, p.572-573) and was filled with numerous Nikkei businesses. When looking through a newspaper advertisement from the time, one can find references to the Nakaya store which was run in a five story building at the entrance of Conde de Sarzedas Street, Ueji Ryokan which is said to be the first Nikkei ryokan (Japanese inn), Tokiwa Ryokan, Aoyagi Tei, Murakami Dental Clinic, Kaneshiro Yamato Dental Clinic, Kunī store, Watanabe gun store, Hase store, and Endō Tsunehachirō store.

In 1933, there were 3000 Nikkei residents (600 families) living within São Paulo city (80 Year of History, p.127). Most of these city-dwelling Nikkei had moved into the Conde District from rural areas between 1917~1918. The reason being that the area was close to the center of São Paulo city where there were more jobs available and because it was located near communal resources for the Nikkei such as the Japanese consulate-general, Foreign Industrial Enterprise Office, and the Brazilian Tsuge Association Office. Further, the rent was cheap in the Conde District. The Nikkei residences during these times were located beyond Conselheiro Furtado Street and extended west along Estudantes Street, Galvão Bueno Street, and Fagundes Street. The reason for the later centering of the Nikkei school system in the Liberdade District was because of the same reasons for such Nikkei residence.

There was a Brazilian researcher who gained interest in the Japantown of the Conde District in this time. His name was Oscar Araújo and he had studied Chicago School Urban Sociology under Donald Persson at the São Paulo Public Community Institute (Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo) in the 1930s. He describes the conditions of the Conde District in the mid-1930s from a Brazilian point of view.

Most of the shops on this street are run by Japanese, creating a fascinating Oriental atmosphere. Here, one can easily encounter the refinement and customs only the Japanese have, through their delicate and intriguing clothing accessories and goods directly imported from Japan such as ‘Ajinomoto’ (MSG) and ‘Shinyō Curry.’ And these must be the stores’ advertisements and signs. Some of them use special characters, ones of the Land of the Rising Sun. This is the store-front sign of a Japanese boardinghouse. There, a Japanese hotel. And over there, I believe is a barber shop, and a laundry. One can find everything here; a vegetable market, a butcher, a confectionery shop, a furniture store, a shoe store, a drugstore, a bookstore, and even a bank (AREÚJO, 1940, p.237).

One can see that the Conde District exhibited so many aspects of a Japantown that it fascinated a Brazilian researcher. It was on February 2nd, 1942 that a sudden order was made to stay away from the Nikkei residents of the area. It was for reasons of public order.

Even before then, there was strong animosity towards Japanese, German, and Italian (Axis Power countries) residents due to the growing assimilation ideology of the Estado Novo (New State)1,which was established in 1937 by the Getúlio Vargas Administration (Sumida, 2000, pp.127 - 129).

All foreign language schools were shutdown by December of 1938, a foreigner registration policy was implemented in January of 1940, and the acquisition of an identification card became mandatory. Further, the printing of foreigner newspapers was banned in August of 1941, and in the same year, the Pacific War would soon begin. After the outbreak of the Pacific War, diplomatic relations between Japan and Brazil were broken off in January of 1942, followed by the closure of the embassy and other such foreign government establishments. A second, 10 day seclusion decree was order on the Nikkei residents of the Conde District on September 6th. Japanese government organizations had already withdrawn from the country on July 3rd and so there was no government authority to protect the Nikkei residents at the time.

Mr. ME (born in São Paulo City in 1922), who sold Japanese books, imported records, and stationary at the Endō store on Bonita Street (now Tomas de Lime Street), which intersects Conde de Sarzedas Street, states the following.

“I believe it was 1942 when an evacuation order was give by the Security Bureau to leave the Conde within 24 hours. My older brother and I went to the police and asserted that we were Brazilians who had even done military service. However, the policeman stated that, ‘All you people with Japanese faces are Japanese.’ In the end, we had to close down our business and move out.”

Though the consulate-general, before it was shut down, distributed a letter to each Nikki business and owning family which read “Let us not lose our magnanimity as a people… and continue to work hard,” the Nikkei of the Conde District, not being able to speak Japanese, gradually disbanded in silence (ACAL, 1996, p.31). From around the same year, there were numerous accounts of Nikkei being arrested by the police. Issei, being in a leadership position, began to carry around spare underwear, a towel, toothpaste and a tooth brush when they left home in case they were arrested. By this time, one could rarely catch sight of a Nikkei person in the Conde District.

Though the people of descent from the Axis Powers were forced into trying times in this way, it is said that most of the Nikkei believed in Japanese victory in the war. On June 6th, 1945, Brazil declared war on Japan and on August 15th of the same year, Japan surrendered. Thereafter, Brazilian Nikkei society entered into a chaotic post-war era branded by victory and defeat.

Then what did the Nikkei immigrants do in the post-war era after being cast out of the Conde District? It is believed that this decree caused Nikkei immigrants to move to the suburban districts within São Paulo city such as Vila Mariana, Saúde and Jabaquara. It is true that the previously listed districts are known to have many Nikkei immigrants to this day. However, according to my interviews, there are some who moved back to the Conde District and the surrounding areas such as the Liberdade District relatively quickly. Ms. SA, who currently runs a drug store on Galvão Bueno Street, said that her family ran a boarding house along Conde do Pinhal Street after the war. The family had moved to the Vila Mariana District due to the evacuation decree but soon returned back to Galvão Bueno Street after the war and opened a restaurant there. Mr. YK, who had run a corner store on Conde de Sarzedas Street until around the year 2000, had moved to Paraná state during the war, but had frequently return back to São Paulo due to this work delivering grain to the Central Municipal Market. On August 15th, 1945, he had gone to São Paulo and states he saw a poster reading “Japan Victory!” in the Conde.

As a glimmer of good news within this chaos, in January of 1948, Yukishige Tamura, a Nisei born in the Japantown of the Conde and a graduate of Taishō Elementary School, was able to win an election due to another's death or disqualification and become a councilman of São Paulo city. Tamura later advanced through the São Paulo state legislature and in 1954, became the first Nikkei member of the lower house.

In 1953, the same year the first, post-war Japanese immigrants (51 passengers) arrived on the Dutch vessel Cisadane, Brazil’s first Japanese movie theater Cine Niterói opened along Galvão Bueno Street in the Liberdade District, the same district as the Conde neighborhood. This movie theater would later become one of the reasons the new Japantown would be established in the area (NEGAWA, 1998, p.243; 2001, p.105; Negawa, 2006, pp.131-134). As I will mention later, Galvão Bueno Street became the center of the new Japantown due to the numerous shops catering to the crowds of the movie theater.

However, until the 1970s, the Conde District Japantown still rivaled Galvão Bueno Street. According to a newspaper article at the time, comparing the developing Galvão Bueno Street, “the former ‘star’ Conde District has modernized due to expanded roads and simultaneously, shown a strong comeback with Nikkei stores opening their doors” (Nippaku Mainichi Shinbun, 7/9/1969). According to such statements, it seems the Conde District Japantown was in ‘co-existence’ with Galvão Bueno Street.

In fact, Mr. SO, who became the third president of the Liberdade Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACAL) chose to open its first jewelry store in the Conde District. Further, Paulista Newspaper, one of the three major newspapers along with São Paulo Newspaper and Nippaku Newpaper, held its headquarters, editorial department, and printing factory on Oscar Sintra Gordinho Street, which intersects Conde de Sarzedas Street at the base of the hill, until March of 1998 when the company merged into Nikkei Newspaper. Such facts show that an era of ‘co-existence’ of the two Japantowns lasted for a while.

With the numerous Korean immigrants to Brazil starting in 1963, however, many Koreans took up residence along Conde de Sarzedas Street by the 1970s. According to Mr. SC, who moved to Brazil in 1972, many Koreans immigrants were involved in the sewing industry and the sound of sewing machines could be heard all night long from the old apartments of the Conde area. Further, Mr. SC described (in Japanese) Conde de Sarzedas Street as being a “brothel town” in those times and as a shady area where prostitutes loitered in the streets even in the afternoon. Such a development of a co-existence between ‘old-timer’ Nikkei residents and ‘newcomer’ Korean residents is quiet intriguing.

Note:

1. According to Sumida (2000), the Estado Novo (New State) was an authoritarian government set up by Vargas. “It is believed that Vargas was able to acquire the support of an order under the Portuguese authoritarian of the time, Salazar. The order clearly displays the tide of fascism centering in Europe in those days.” Further, “The rise of nationalism is a characteristic of Vargas’s authoritarian government… government policies focused on pressing forward the unification of the country through the establishment of an authoritarian government by means of revolution. Superficially, the participation of the people in government was emphasized and government policies were said to focus on helping the people of Brazil through the country’s shared mentality, or “Brazilidade” (pp.127 - 128). As for the assimilation policy of immigrants, “In the midst of the growing tide o nationalism, the assimilation policy towards immigrants was implemented and by 1938, an Immigrant Deliberation Group was established. Its function was the ‘Brazilification’ of immigrants” (p.128).

References:

Sumida, Ikunori (2000). “Shin shidōsha Vargas” (The New Leader Vargas) Norio Kinnshichi, Ikunori Sumida, and other authors compilation Burajiru kenkyū nyūmon - Shirarezaru taikoku 500nen no kiseki- (Introduction to Research on Brazil - The Locus of a 500 year old Lost Empire) Kōyōshobō pp.121-129

Negawa, Sachio (2006). “Maruchi esunikku toshi san Paulo ni okeru ‘nihon bunka’ no hyōshō -Tōyō gai ni okeru shinn dentō gyōji o chuushin ni-” (Symbols of ‘Japanese Culture’ in the Multiethnic São Paulo -Centering Around New Traditional Events in Japantown-) Heisei 16~17nen kagaku kenkyū hi hojokinn (Kiban kenkyū C) Kenkyū seika houkokusho / gendai Burajiru ni okeru toshi mondai to seiji no yakuwari (Supplementary Aid for Scientific Research Costs for the 16~17th year of the Heisei Era (Base Reasearch C) Report of Results/ Current Problems and the Role of Politics in the Cities of Brazil) pp.129-140

Handa, Tomoo (1970). Imin ni seikatsu no rekishi -Burajiru Nikkei jin no ayunda michi- (The History of Life as an Immigrant -The Path of the Nikkei in Brazil) São Paulo Center for Japanese-Brazilian Studies

ACAL (1996) Liberdade. ACAL

AREÚJO, Oscar E. (1940) “Enquistamentos Étnicos”. In. Revista de Arquivo de Municipal de S.Paulo LXV. São Paulo, Divisão do Arquivo Histórico pp.227-246

NEGAWA, Sachio (1998) “San paulo tōyō gai no keisei to henyō ni kansuru nōto” (Notes on the Formation and Changes in São Paulo Japantown) In Anais do IX Encontro Nacional de Professores Universitários de Língua, Literatura e Cultura Japonesa e I Encontro Latino Americano. Assis, Unesp pp.242-249

__________ (2001) “Um Comerciante Japonês: História de Vida no Bairro Oriental de São Paulo”. In Estudos Japoneses 21. São Paulo, FFLCH/USP pp.101-115

Newspaper Articles

“Yosooi mo aratani - Yomigaeru Conde San Paulo nihon jin machi shin chizu” (A New Look - New Revived Conde São Paulo Japantown Map) Nippaku Mainichi Shinbun Vol. 5085 (July 9, 1969)

© 2007 Sachio Negawa